Contents

Humans have been making art for more than 30,000 years. Even before civilizations became established, paintings and sculpture were created, often showing remarkably advanced and sophisticated artistic skills. As societies evolved, materials, processes and techniques developed, and the art that was produced changed to suit new, changing lifestyles.

Over the centuries, art has been made by almost all societies. For ease of understanding, much of it is grouped into movements, schools, periods and styles, often retrospectively by art historians, or sometimes by the artists themselves. But not all of it can be categorized. The history of art is never regular or predictable, and it constantly changes. Rarely created in an isolated moment of inspiration, it is nearly always an amalgam of circumstances and experiences, feelings and opinions, social, environmental or political situations, or developments in technology, beliefs, traditions or thinking. It is also always about endeavour, ability, process and product. Which is why it manifests in such a multitude of ways, and expresses anything from the universal to the commonplace.

Additionally, art has many functions. While much of it appears to have been created in imitation of the world, it is much more than that. It mirrors the times in which it has been made and, depending on the culture and location, can express and emphasize many different things, such as beauty, truth, death, order, immortality, power or harmony. As a form of communication or decoration, it can express philosophical points or religious beliefs, or it may simply entertain. Like another language, art becomes more fascinating when it is understood.

This book offers insights into a huge variety of art, from the earliest to the most recent. Its for anyone interested in art, from those who know a little, to those who know a lot. Roughly chronological, it considers many of the main developments in art throughout history and the world. In analyzing and appraising many inventions, ideas, materials and influences, backgrounds, skills, attitudes and approaches of groups of artists, skilled and talented individuals, and even those who produced just one ground-breaking work of art, the book interprets and explains over 30,000 years of art in minutes.

L ong before humans invented writing, they created art. The oldest art so far found was made around 38,000 BCE , in the Stone Age Upper Palaeolithic period, and was probably connected to belief systems. Some of the earliest art was three-dimensional: small stone, ivory or bone female figures known as Venus figurines (although far predating the Roman myth) are the best known. Found in various parts of the world, they all share similar physical attributes, including short legs and arms and exaggerated breasts, bellies and thighs, suggesting that they may have been fertility icons. The most famous is the 11 cm (4 in) limestone Venus of Willendorf from Austria, made c .28,00025,000 BCE .

As well as humans, Stone Age sculptors carved animals. South Korean figures carved on deer bone have been dated to around 38,000 BCE , and were probably good luck charms. The oldest known anthropomorphic carving is the Lion Man of Hohlenstein Stadel from Germany, a lion-headed human figure of similar age.

Venus of Willendorf , c .26,500 BCE

T he first painters made images on rocks and cave walls using natural pigments, mixed with saliva or animal fat, and applied with fingers, sticks, moss or bones. The most famous are lifelike paintings of animals, including bison, horses and cattle. Sometimes natural variations on the walls were used to create three-dimensional effects. The inaccessibility of most of these caves suggest that they were not dwellings, but that the paintings were probably part of religious rituals, perhaps intended to evoke hunting success.

Despite the crude materials and the conditions in which they worked, many Palaeolithic artists demonstrate accomplished skills in rendering tone, movement and foreshortening. This is apparent at Lascaux in southwest France, where about 300 paintings and 1,500 engravings decorate two large caves c .17,300 years old. Similar images have been found in other caves across the world. Few realistic humans are depicted instead, human presence often appears as hand prints.

Lascaux cave painting, c .17,300 BCE

O ften called the Cradle of Civilization, Mesopotamia comprised an area roughly corresponding to present-day Israel, Iraq, part of Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey and Syria, and flourished c .4,000500 BCE . Neolithic cultures flourished here and it was the site of numerous inventions, including the first writing system, the wheel, the arch and the plough, and also saw the earliest implementations of law, medicine and science. Sophisticated irrigation systems also generated abundant harvests, leading to healthier populations.

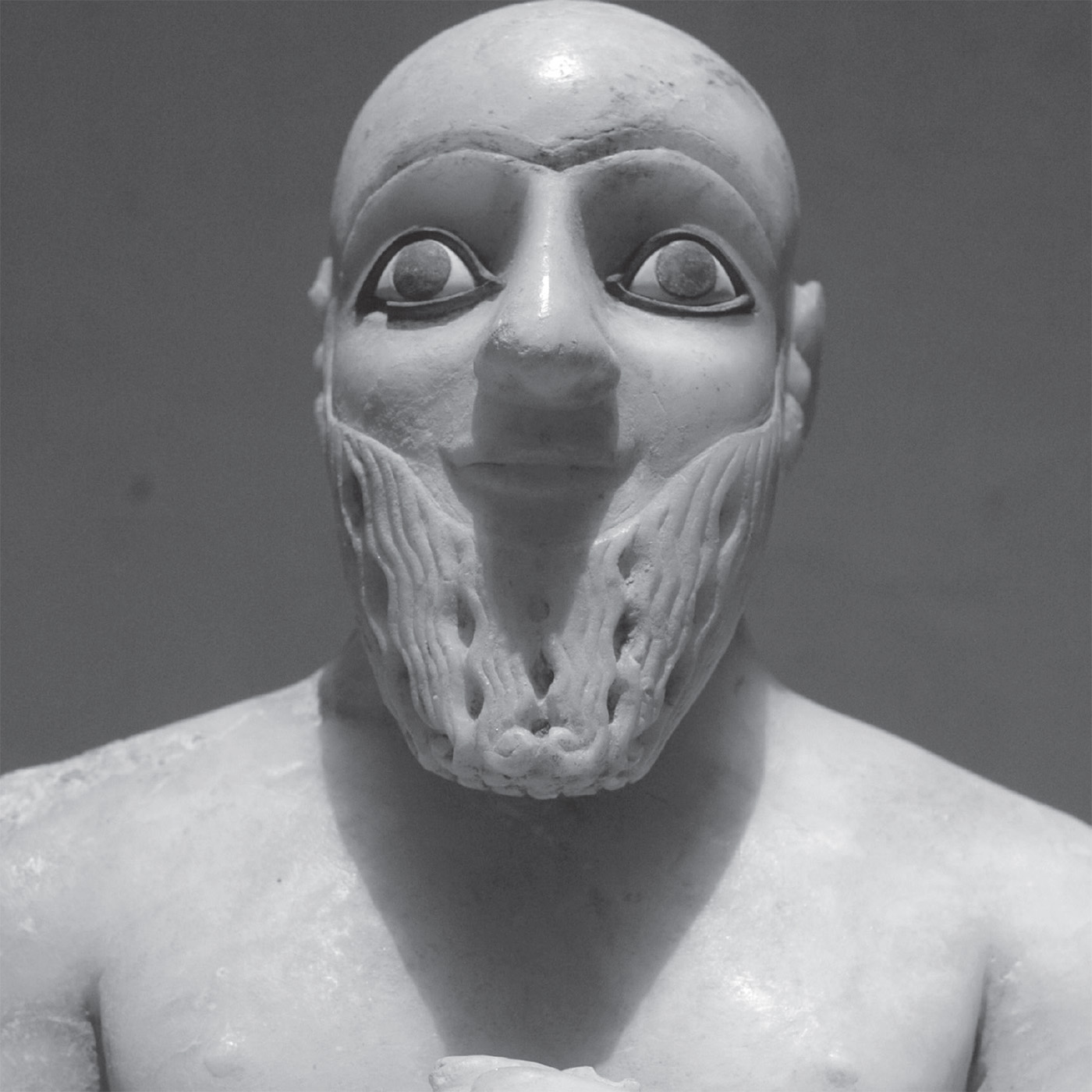

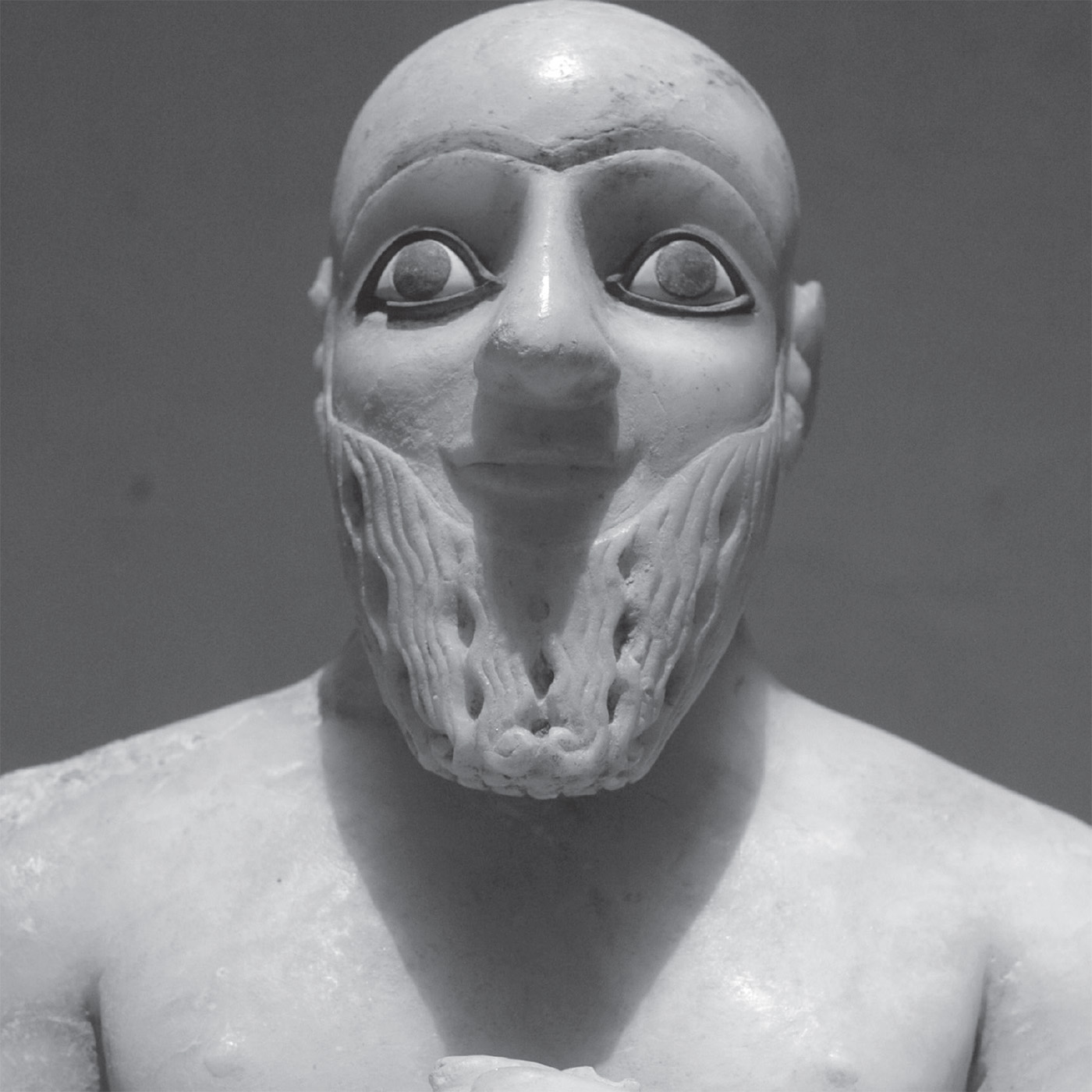

The first Mesopotamian civilizations were the Sumerians and Akkadians. From c .4000 BCE , the Sumerians produced art that expressed their relationships with their gods and the natural world. In c .2300 BCE , they were conquered by the Akkadians. With slight differences, both civilizations produced ceramics, stone and clay statues, reliefs, steles and mosaics. Lifelike animal forms and human figures predominated. Fairly detailed, they are also rigid-looking, while figures and animals have large, expressive eyes.

Bust of Ebih-Il , c .2400 BCE

T he city of Babylon lay south of present-day Baghdad. During the Old Babylonian Kingdom ( c .18941595 BCE ) King Hammurapi (179250 BCE ) defeated the other southern states and unified the former kingdoms of Sumer and Akkad. Sculpture predominated during this period. The New Babylonian Kingdom (627539 BCE ) achieved particular greatness in the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II (605562 BCE ). He rebuilt Babylon, surrounded it with massive walls and, c .575 BCE , built the huge Ishtar Gate, adorned with colourful reliefs of symbolic beasts, including bulls, lions and snake-dragons.

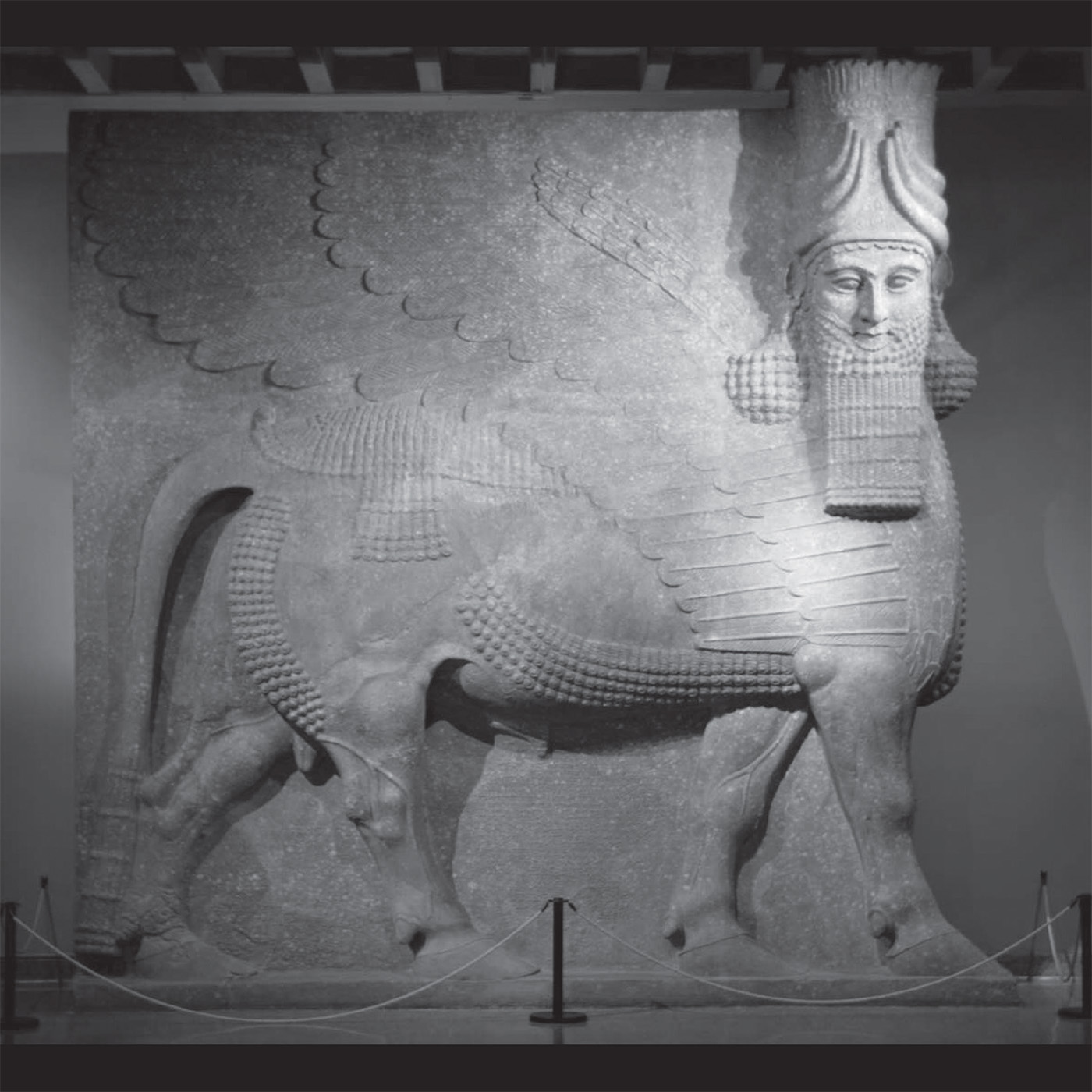

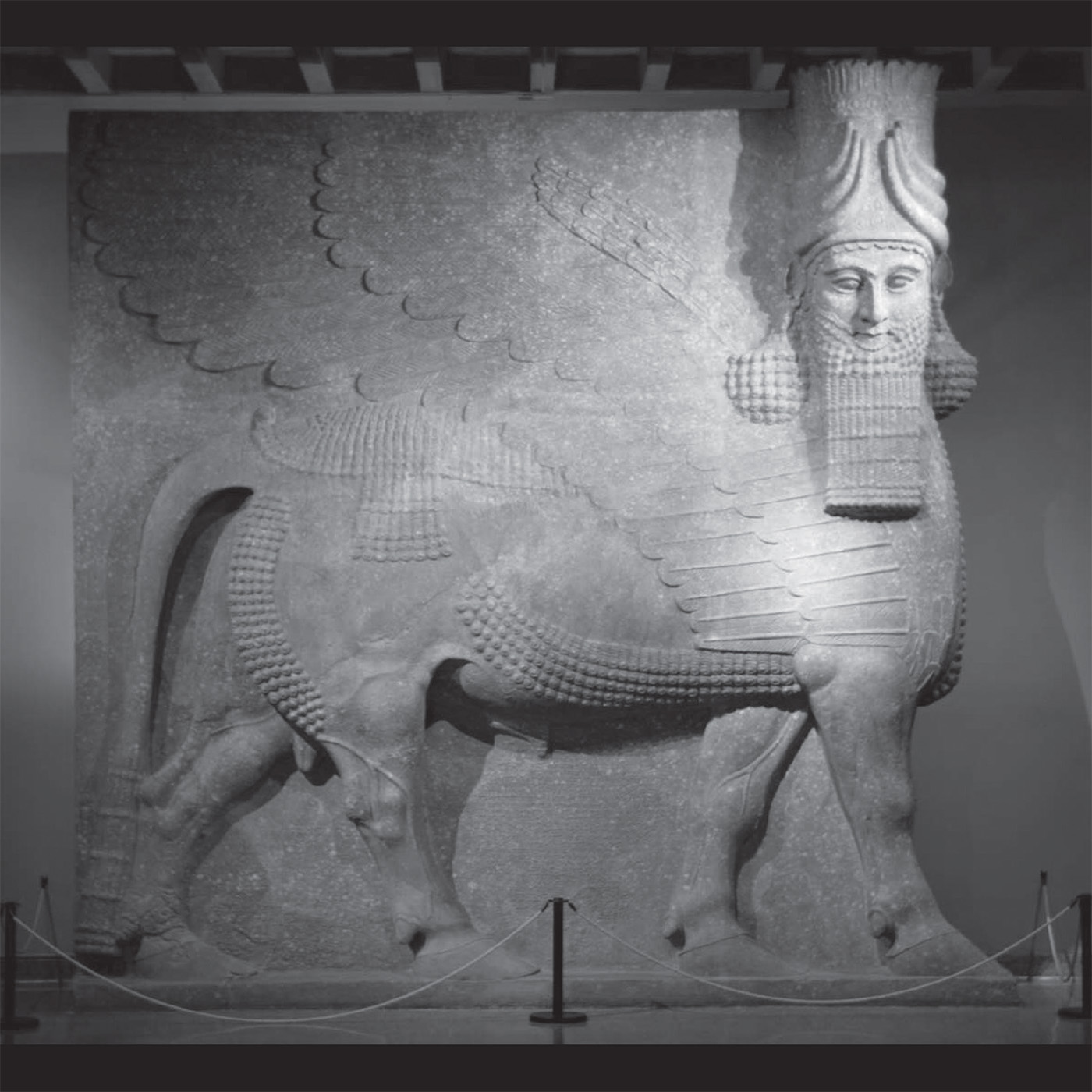

The Assyrians of northern Mesopotamia ruled c .2500605 BCE , and were at their peak in the Neo-Assyrian period (883612 BCE ) when huge carvings of mythological Lamassu, or winged guardians, were installed in the palace of King Ashurnasirpal II (883859 BCE ) at Nimrud. They constructed lavish palaces and temples in different capitals, including Nimrud, Ninevah and Khorsabad, and filled them with monumental statues and reliefs, often glorifying the king, depicting battle scenes, grand banquets and people bearing gifts.

Lamassu figure from Khorsabad, c .710 BCE