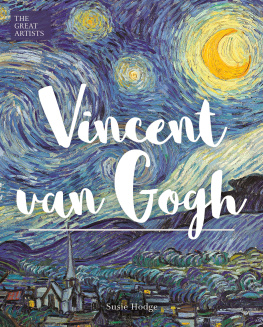

.jpg) Self-Portrait

Self-Portrait, 1889. Vincents painting style of thick impasto paint, obvious outlines and expressive colours contradicted accepted styles of his time. Through his portrayal of emotion using all these elements, he changed the course of art.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most legendary artists in history, Vincent van Gogh (185390) has been the subject of many books, films and songs yet he did not achieve fame until after his death and his troubled and tragic life was spent in poverty. While he is now admired the world over for his colourful, expressive paintings and emotive drawings that paved the way for Expressionism, Fauvism and other modern art movements, he made art that was at variance with the accepted artistic approach of his times. Most of his work was produced over just ten years, while he was struggling with both physical and mental illnesses, and when he died at just 37, he left a remarkable legacy of approximately 2,000 works of art and hundreds of letters that reveal his extraordinary thought processes and vision.

After trying several different careers for which he proved unsuitable, Vincent decided to become an artist a choice that was only made possible by the emotional and financial support provided by his brother Theo. With an earthy palette and strong chiaroscuro (dramatic contrasts of tone), his earliest art followed the Dutch tradition before he joined Theo in Paris and learned from the avant-garde artists of the day. As soon as he reached Arles in the south of France, his genius emerged. He knew that he was exploring a completely new way to use dazzling colours and thick, expressive brushstrokes to convey emotion, and despite it not being appreciated, he continued in his own style, painting landscapes, night scenes, peasants at work, sunflowers and self-portraits. His bold experimentation was unprecedented and produced at huge risk to his health and sanity, but the intense emotions he experienced in his life can be seen in every work of art that he created.

This book is part of a series introducing great artists who changed the course of art. It charts Vincents journey as an artist, exploring the places he lived, his often fraught relationships, how his individual style evolved, and the artistic influences that contributed to his extraordinary legacy.

A Watermill in a Woody Landscape

A Watermill in a Woody Landscape, Lodewijk Hendrik Arends, 1854. Landscape painting became a popular genre in Dutch art during the sixteenth century, and paintings of the Dutch landscape remained sought after in the nineteenth century. The young Vincent grew up extremely aware of the national tradition.

On 30 March 1852, Anna Cornelia van Gogh, wife of the Reverend Theodorus van Gogh, gave birth to a stillborn son whom the couple named Vincent Willem. Exactly one year later, on 30 March 1853, they had another baby boy, this time strong and healthy, to whom they gave the same name. Vincent was followed by five siblings: Anna, Theodorus, or Theo, Elisabeth, or Lies, Wilhelmina, or Wil and Cornelius, or Cor.

The family lived in the Dutch village of Groot Zundert in North Brabant, close to the Belgian border. Theodorus was a pastor in the Dutch Reformed Church, and Vincent grew up in a devout household; his parents were quiet, modest people who regularly moved from one small parish to another. Vincent and Theo shared a bedroom in Groot Zundert and became especially close.

At the age of 11, Vincent was moved from the local village school to a boarding school in the town of Zevenbergen, 25 km (15 miles) north of Groot Zundert. Although unhappy there, he stayed for two years until he was transferred to another boarding school in Tilburg, approximately 45 km (28 miles) from Zundert. Little is known about his education except that he was good at languages and became proficient in English, French and German; that drawing was a large part of the curriculum; and that he left his last school halfway through his second academic year when he was 15, although it is not clear why.

First job

Vincents Uncle Cent (also Vincent van Gogh) had recently retired from his job as an art dealer, and he found the 16-year-old Vincent a position as a trainee at the international gallery Goupil & Cie. With headquarters in Paris and branches in London, Brussels, The Hague, Berlin and Vienna, Goupil & Cie specialized in French contemporary art. Vincent began working in The Hague branch. His boss recounted that he began eager and ambitious and with a friendly manner towards everyone. In the summer of 1872, he went home to Helvoirt, where his father had been given a new parish. Theo joined them from school and during that holiday, the two brothers agreed to support each other and correspond regularly. This correspondence continued for the rest of Vincents life, except for a short time when they lived together in Paris. The following September, Theo left school and also began working as an art dealer at Goupil & Cies branch in Brussels. Meanwhile, Vincent was transferred to the London branch.

Portrait of Theo van Gogh

Portrait of Theo van Gogh, 1887. This small work was long thought to be a self-portrait, but after much research it is now believed to be of Theo, and possibly the only portrait of his brother that Vincent ever made.

Flower Beds in Holland

Flower Beds in Holland,

c.1883. Vincent made this painting when he returned to live in The Hague a few years later. From a low viewpoint, he uses linear and aerial perspective to draw the viewers eye into the scene. The colourful tulips in the foreground contrast with the dark thatched cottages and bare tree trunks in the distance.

The letters

Almost 1,000 letters survive from Vincents life, written by, to or about him. Although he did not keep many that he received, there are more than 650 in existence that he wrote to Theo. Others survive, such as several he wrote to his sister Wil and other relatives, and to his artist friends including Paul Gauguin, mile Bernard, Eugne Boch and Anthon van Rappard. When he died, a letter he was writing to Theo was discovered unfinished in his pocket.

The letters reveal much about Vincents ideas, working processes and the evolution of his art. They are a record of a passionate and intense man who often felt isolated and lonely, and it is largely through these letters, first published in 1914, that we know how much Theo did for Vincent, and how much gratitude and guilt Vincent sometimes felt about it. In one letter he wrote: I will give you back the money or give away my soul. In another: I have to thank you for quite a few things, first of all your letter and the 50-franc note it contained, but then also for the consignment of colours and canvas that Ive been to collect at the station.

Vincent poured out all his thoughts in his letters, from the small details of everyday life to his more profound beliefs about existence, his psychological difficulties and his vivid imagination. He described his feelings as well as events that happened to him, his views on colour theory and contemporary literature he was reading. Frequently illustrated, his letters also show how he planned his paintings. In words and drawings, he described people, places, colours, and his anxieties and preoccupations about his art. The letters are a record of his great struggle; his knowledge that he was trying to do something special and extraordinary, while also being full of self-doubt and lacking self-esteem. Yet despite all his insecurities and health problems, he was firm about his art, for instance: I want you to understand clearly my conception of art What I want and aim at is confoundedly difficult, and yet I do not think I aim too high. I want to do drawings which touch some people.

.jpg) Self-Portrait, 1889. Vincents painting style of thick impasto paint, obvious outlines and expressive colours contradicted accepted styles of his time. Through his portrayal of emotion using all these elements, he changed the course of art.

Self-Portrait, 1889. Vincents painting style of thick impasto paint, obvious outlines and expressive colours contradicted accepted styles of his time. Through his portrayal of emotion using all these elements, he changed the course of art.  A Watermill in a Woody Landscape, Lodewijk Hendrik Arends, 1854. Landscape painting became a popular genre in Dutch art during the sixteenth century, and paintings of the Dutch landscape remained sought after in the nineteenth century. The young Vincent grew up extremely aware of the national tradition.

A Watermill in a Woody Landscape, Lodewijk Hendrik Arends, 1854. Landscape painting became a popular genre in Dutch art during the sixteenth century, and paintings of the Dutch landscape remained sought after in the nineteenth century. The young Vincent grew up extremely aware of the national tradition.  Portrait of Theo van Gogh, 1887. This small work was long thought to be a self-portrait, but after much research it is now believed to be of Theo, and possibly the only portrait of his brother that Vincent ever made.

Portrait of Theo van Gogh, 1887. This small work was long thought to be a self-portrait, but after much research it is now believed to be of Theo, and possibly the only portrait of his brother that Vincent ever made. Flower Beds in Holland, c.1883. Vincent made this painting when he returned to live in The Hague a few years later. From a low viewpoint, he uses linear and aerial perspective to draw the viewers eye into the scene. The colourful tulips in the foreground contrast with the dark thatched cottages and bare tree trunks in the distance.

Flower Beds in Holland, c.1883. Vincent made this painting when he returned to live in The Hague a few years later. From a low viewpoint, he uses linear and aerial perspective to draw the viewers eye into the scene. The colourful tulips in the foreground contrast with the dark thatched cottages and bare tree trunks in the distance.