Personal Recollection of

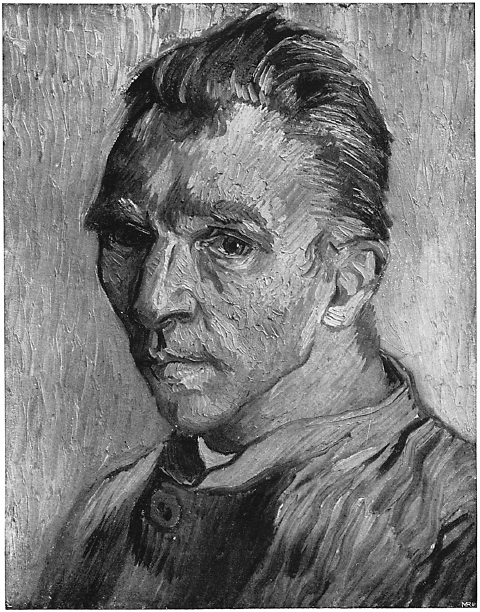

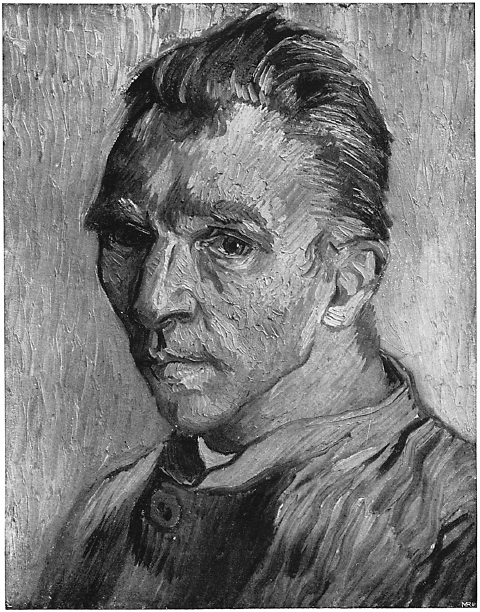

Vincent Van Gogh

VINCENT VAN GOGH

painted by himself

Personal Recollection of

Vincent Van Gogh

Elisabeth Duquesne Van Gogh

Translated by

Katherine S. Dreier

With a Foreword by Arthur B. Davies

Dover Publications, Inc.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2017, is an unabridged, corrected republication of the work originally published in 1913 by the Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gogh, Elisabeth du Quesne van, 1859-1936, author. | Dreier, Katherine Sophie, 18771952, translator.

Title: Personal recollections of Vincent van Gogh / Elisabeth Duquesne Van Gogh ; translated by Katharine S. Dreier.

Other titles: Vincent van Gogh. English

Description: Mineola, New York : Dover Publications, Inc., 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016039351| ISBN 9780486809069 (paperback) ISBN 0486809064

Subjects: LCSH: Gogh, Vincent van, 1853-1890. | ArtistsNetherlandsBiography. | BISAC: ART / Individual Artists / Essays. | ART / Reference.

Classification: LCC N6953.G63 G64 2017 | DDC 759.9492dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016039351

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

80906401 2017

www.doverpublications.com

EENder allerbelangrijksten, zeker de opmerkelijkste schilder uit het heden in zijn waarachtigheid als kunstenaar, is de eerbiedwaardige, verhevenheid van Van Gogh.

W. STEENHOFF, Groene Amsterdammer.

Admirez-vous les uns les autres,

Admirez lhomme et admirez la terre,

Et vous vivrez ardents et clairs;

La vie est monter et non pas descendre,

Nous apportons, ivres du monde et de nous-mmes,

Les curs dhommes nouveaux, dans le vieil univers.

EMILE VERHAEREN.

There is no genius without a tincture of madness.

SENECA.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

.

FOREWORD

THE paintings of Van Gogh show soundness and lucidity of mind, in form and in color, and contain sure indications of generous human sympathies. All this combines to make an art work which is essentially aristocratic. His powerful stride leads us into the domain of cosmic unity, where the great artists cluster in Pleiades. Because so satisfyingly permanent they give that zest to life, showing that the ascendency of any human being, though handicapped by depressions and the sense of imminent misfortunes, will prevail over all those seemingly inherited material conditions.

It is blindness not to recognize in Van Goghs paintings a fine balance of faculties, simplicity, and seriousness based upon a natural expression. He had no eye for compromise, for the devil of academic security of possession. He has ruled his domain with kingly power and made his visions beautiful, painting them in characters of rugged construction.

To see his master works is to realize his loyalty to his subjects, a singleness of purpose which is almost painful. His masterstroke is a prayer of thankfulness, his final thought a law of eternal energy.

As a seeker after some new spirit, Van Gogh again verifies that, in avoiding conventional realism, art is vitally augmented change, suggesting so much, completing so little, yet conformable to the natural order of intuition and duration.

The ordinary person is not naturally delighted with a great break, as made by Cezanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, and Brancusi; with the determination not to go on imitating facts but to produce, instead, things of plastic, decorative beauty. Mankind nevertheless is always able to discern that sincerity is a necessity of occupation in an art work, and that there is a relation of the fact to the perfect idea, and to the perfect artist.

ARTHUR B. DAVIES.

INTRODUCTION

D URING the summer of 1912, Der Sonderbund of Cologne held an exhibition of modern paintings, representing especially those painters of various nations who are trying to express not only themselves but the spirit of to-day.

Europe is greatly in advance of us in this respect, ready to give a hearing to a group of earnest thinkers in whatever branch of thought, be it science or the arts. This is especially true of France, and that hospitable city, Paris, which is always ready to share all its knowledge and its thoughts with those who wish to enter its portals. Who has not heard of or met with those kind French dealers, men of moderate means, of plain birth, whose passion for art has made them true patrons, in the real sense of the word men who have given assistance to young, struggling, and unknown painters or sculptors; who gave them their first chance by placing their work in their show-windows, or, by giving credit for material, offered them the first real opportunity for work; who, when asked by commercial friends whether the loss was not great, answered, as did Pre Foinet, No, for they always pay back unless death instead of fame first overtakes them!

Germany, too, is trying to bring to life this spirit, in forming art associations throughout her large cities, which will enable artists to exhibit their work at almost no expense.

One of these new associations representing the modern movement is the Sonderbund of Cologne, which held an exhibition last year. From all over Europe people came to see and to learn. It was held in a large temporary structure, and of the twenty rooms, four were given over entirely to the works of Van Gogh. One hundred and twelve of his paintings had been gathered together from collections scattered throughout Europe. Here at last was an opportunity to study the works of a man who was deeply impressing and influencing artists and critics in many countries. They were not slavish followers, imitators, that one met, but men who were doing vigorous original work. Van Gogh seemed to have stimulated and opened out to them a whole new vision of color construction.

We reached Cologne after a long, dusty railroad journey and immediately drove out to the exhibition. The first room that one entered was the large hall with a single line of Van Goghs paintings, all done in his last and most brilliant period, hung spaciously, so that each picture came to its full value.

It was like stepping out of a stuffy room into glorious, bracing air.

What courage and conviction had produced this vitality these pictures vibrant with life!

How did Van Gogh secure this result?

The foundation of it allhis mindwhat was it like, that made this extraordinary personality what it was?

That was the question that kept repeating itself, and I read all that I could find about him, in the hope of having it answered.

This simple, exquisite appreciation written by his sister seemed to me to give one more truly a keynote of understanding of his work than all the technical dissertations on his methods and achievements. Here, through his sister, one has the privilege of an intimate and sincere introduction into the life and work of the man. He had a broad education, a great capacity for work, a fine intellect, fed by incessant study, which, when concentrated upon art, developed both theory and practice. His knowledge of many languages opened out vast fields of literature on art and chemistry, and nothing which could be found relating to these subjects escaped him. The single-mindedness of his life alone made possible the progress which he achieved.

It was, however, also the philosophical problems of life that consumed him, and his tremendous concentration caused the tragic temporary mental breakdowns. For critics, therefore, to emphasize these periods of depression and insanity, as if the saneness were but a matter of lucid intervals, is about as unfair a proceeding as one can find. The conclusion of one critic, that Van Gogh was unable to think straight because of them, tempts one to ask the objector how many pictures by Van Gogh have been seen and studied, not how many books or articles have been read?

Next page