Acknowledgements

Thank you to Wilma, Robert & Kathryn Murphy for familial support, to Owen Hatherley, Joel Anderson, Ian Abley & Brad Feuerhelm for image assistance, to Kathryn & Owen for reading and comments, to Tariq Goddard and all at Zer0 books, and to everyone else who helped me in some way.

Conclusion

Should the comparison between contemporary architectural culture and the late 19 century be taken seriously? Although it has a neatness to it, it is not my intention to posit some kind of perfect cycle of history here; it is enough to point out that the bearers of the avant-garde legacy actually have more in common with the culture against which modernism defined itself than they do with radical modernism itself. But though we might crave a repetition of the modernist event, it would be too simple and nave to expect there to be some new methodology waiting in the wings of architecture, ready to sweep away the academicism and confusion of the current period, defining new forms of space for new cultural movements. But are there lessons we can draw from this problem?

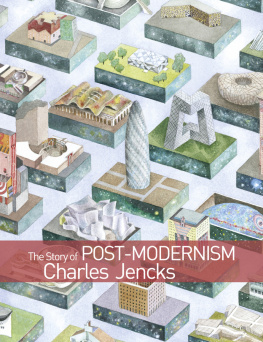

Against the monumentality and eclecticism of the current period of cultural buildings, we might return to our discussion of digital space and note that the hyper-connectivity of the digital world generates similar reactions to those which the iron & glass revolution inspired; it functions both as a symbol of utopia for radicals, democratic, universal, free, but also as a terrifying symbol of control; trails of information, security networks and so on. Perhaps we should be widening the question, and noting that mass-produced architecture never achieved hegemony; our environment is filled with spaces from various times and with various histories; the city qua archive is still strong. Perhaps we can posit a not-too-distant time when digital space makes up a large but not overwhelming part of our experience, adding to, overcoding but not replacing previous forms of space. Rather than the virtual reality of the 1980s, we may enter the period of augmented reality. According to this scheme, attempting to create a monumental architectural style for the digital age is no worse than a simple missing of the point, thinking formally in terms of metaphor and historically in terms of the naive cycli-cality that we have just warned against. At the same time this missing of the point also strengthens the thesis that we are living in an eclectic age. Despite spending much of the 20 century beyond denigration, there is an impressive madness to late 19 century design; for example the steroidal Palais de Justice (1866-) in Brussels, or the fairy-tale Midland Hotel (1866-) that conceals the St. Pancras railway shed in London are both fascinating, overpowering and faintly ridiculous buildings; we can compare these to the flamboyance of a Gehry or Hadid building and conclude that they are similarly over the top, but perhaps endearingly so. If we are being as generous as we can honestly be, we might say that the digital flamboyance of todays most modern architecture constitutes something like a jugendstil, an attempt to understand industrialisation/digitisation through filigree and expressiveness.

But this would be too optimistic. The fact is that the poor architecture that manages to get built is a reflection of our depressing political situation. This is nothing new; but certainly it has been strange to see what has happened to modern architecture under the influence of the politics of the last thirty years. The helpless apathy of populations is reflected in the apathy of the designers who are supposedly working at the cutting edge, and this book is at least partly the result of a conviction that the lack of any genuine radicalism in architecture is a deeply negative trend. Hopefully in this book I have managed to shed light upon the ways in which this lack has come about, and alongside the negative clich of architects being moral prostitutes who will work for anyone, we have at least noted that there have been periods where architects were radical, and not just in a navely utopian sense. The fact that we have looked at a number of influential thinkers and practitioners in the field and how they have posed as radicals without any concern at all for institutional critique or ethics is a sad state of affairs, and something that needs to change.

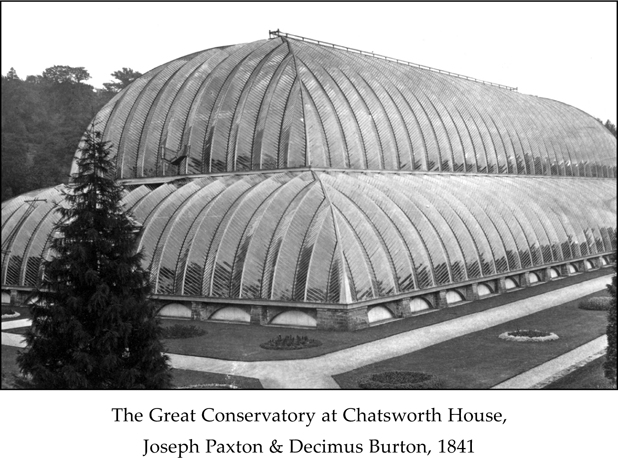

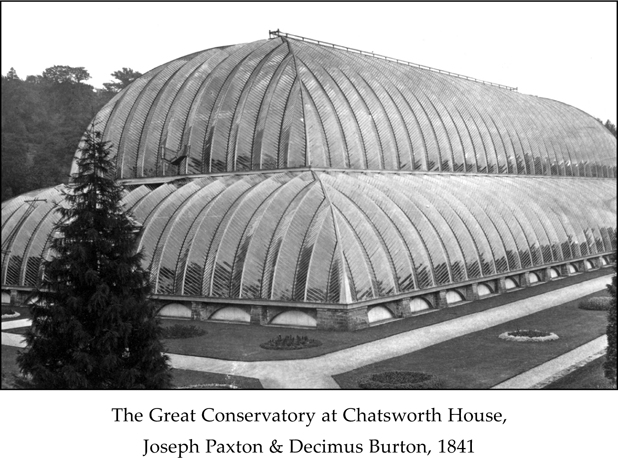

If there is one insight that we have gleaned from this study, it is that there was something unbearable about iron & glass. The failures, the fires, the neglect, the decline, we have followed the paths of weakness in these buildings; again and again we have seen how deeply contradictory iron & glass was; how it symbolised utopia but played an instrumental role in placating working class antagonism, how it promised the future but was swiftly hidden in the fog of the past, how it quickly outperformed the demands that could be made upon it. It could be read as a fantasy of a better world, but it was also a phantasmagoria, a false dream woven from phantom commodities passively consumed by the gaze - it signified both the nightmare of history and the struggle to awake from it. Iron & glass may well have inaugurated a new regime of immersive capitalist space, but once inaugurated, capital retreated back behind monumentality and massiveness. As well as this, totalitarianisms both Soviet and Nazi would also turn heavily towards monumentality, eclecticism and kitsch. Later on, even those who were most influenced by the legacy of iron & glass would simplify its meaning to the point of insignificance.

We have repeatedly stressed how iron & glass buildings inherently rejected many of the very concepts that give architecture its cultural power. In light of the failures and the rejections, it is not too hard to see that the qualities that made iron & glass intolerable are also the very ones that made it so radical. But at the same time we have also seen that these radical qualities are not those of the utopianism usually associated with architecture; the future that iron & glass promised, indeed still promises, was that of rain drumming down on innumerable panes of glass; it was the reverberations of sounds gloomily echoing around a space, it was the dim light falling down from dusty glass, it was a skeleton already overwhelmed by nature even from its birth. Beyond these poetic interpretations; its lightness, transparency and ephemerality set it against conventional architecture; it was a form of building which appeared as a Benjaminian allegory of memory, of objective recollection and its attendant forgetfulness. They were ruins without being ruined, fragments even in their totality. This book has been an attempt to grasp this radical melancholy, to retrieve this vision of a deliriously dreary future, to find in the fragments the grains of something utopian even in its very failure.

Iron & Glass

Of all cultural forms, architectural modernism was perhaps the modernism most directly influenced by specific technological developments. Unlike literature, whose technologies of creation and dissemination remained more or less same from the 19 to the 20 centuries, or music, whose late 19 century development in recording technology - phonography - would be embraced most quickly in the field of popular music, modernism in architecture can effectively be traced back to two events - the development of mass-produced cast iron & plate glass. And again, unlike in literature and music, whose modernisms worked primarily with form and technique, architectural modernism became an ideology in which the industrial would play a most important role. One way to understand this condition is that it is due to the fact that of all cultural forms, architecture is the one that requires the largest amounts of capital to produce; not only the huge masses of material that must be assembled, but also the huge amounts of labour that go into the erection of buildings. If we (not unproblematically) think of architecture as an art form, then it is the art form that is still most directly tied to its patrons, with all the ideological problems that entails. With this in mind, it is understandable that the effects of 19 century technological advances, the new materials and new methods of fabrication, as well as other factors such as rapid urbanisation, and changing political and economic cultures would be felt more deeply in the discipline of architecture than in any other cultural form; and also why modernism in architecture would have such a close and complex relationship to technological advancement.