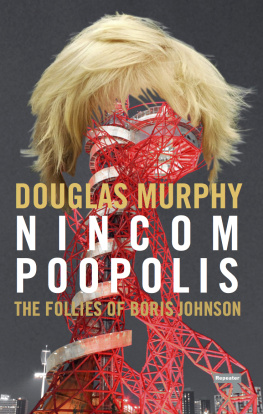

NINCOMPOOPOLIS

NINCOMPOOPOLIS

The Follies of Boris Johnson

Douglas Murphy

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Id like thousands of schools as good as the one I went to

Boris Johnson, Mayor of London

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson, Alex to his family, Boris to the rest of us, was the Mayor of London from May 2008 to May 2016, a strange period that began in the throes of the global financial crisis and ended on the precipice of the UKs Brexit vote. It is no stretch to say that the man is polarising: to some he is Boris the total legend, that rollicking bumbler with the ridiculous hair, a much-needed blast of fresh air blowing through the dank and fusty world of British politics. To others, however, he is the worst kind of upper-class twit dangerous, ignorant, and in possession of a sense of entitlement straight out of the worst days of empire. In a very contemporary way he functions both as a politician and as an entertainment celebrity, in the British context and across the world: as Mayor of one of the worlds major cities he became globally famous, an export symbol of English eccentricity, a cutaway tourists facemask stacked in-between the Queen and David Beckham.

During his eight years in City Hall, there was crisis, disorder, and rioting, there were terror attacks, there was intrigue and corruption. But things didnt fall to pieces under his watch; in fact, it now looks like his period in power was a time of relative local stability in-between crises. The economy of London, massively dependent upon services and the City of London, weathered the storms, and if anything the imbalance between the successes of the capital and the rest of the UK became greater. Outsized wealth became more and more visible during this period, especially in the property market, but also in an upmarket transformation of Londons leisure industry. Johnsons pro-business, pro-wealth message was one of the things that helped maintain Londons reputation as a place to be easily rich, with the 100 million penthouses and 100 steaks to match.

But life didnt get better for most people during this time. The prime force making London life more difficult was housing, with the average cost of a home in London increasing by sixty percent in the eight years Johnson was in charge. But beyond that, cuts in benefits, funding for local authorities and other basic services, imposed by the Westminster government after 2010, made life harder for most of the people in the city. This was the era of austerity, when we were told that the economy was like a cupboard that had been munched empty by the previous government, and that most conveniently antistate cost-cutting was the only thing to be done. Some showboating objections aside, ideologically this was the world that Johnson believed in, and in which Londoners were forced to live.

The built environment of London changed rapidly during the Johnson years, with large volumes of output, most significantly in the private housing sector, but also major transport and infrastructure projects. Areas that had lain dormant for long periods finally saw the cranes arrive, such as the long-gestating Battersea Power Station project that finally began after three decades of failed schemes. Elsewhere, areas of public housing found themselves threatened in a way not seen since the early 1990s, as packs of developers sniffed around the unrealised value in comparatively low-density neighbourhoods of people too poor to afford obscene market rates.

These changes in the built environment were overseen by Johnson, but he had an impact on the form of London far more directly, for during his time at City Hall he conceived of and commissioned a number of projects that to all intents and purposes came directly from his own heart. Ranging from architecture to public art to transport, they rank amongst the stupidest, most ill-conceived works of design Ive seen in my life, a series of whimsical follies stunning not only for the shallowness of their conception, but also for the sheer fact that the unstoppable will of Johnson managed to make so many of them happen.

Almost in homage to one of his beloved classical megalomaniacs, Johnsons interventions in the built environment are some of the most remarkably odd public works anywhere in the world in recent years, monuments to his lack of imagination, and this book is first and foremost about them. It tells the story of how they came to appear, the struggles against them, and the aftermath of their realisation. It is often a story of urban embarrassment, of the shame of having to watch as these objects appeared, but it is also a story of how this kind of personality could achieve such things in a world of faceless business, faceless bureaucracy, endless procurement and tendering processes. It suggests that with the right drive it is still possible to make big things happen, only that in this case its a shame that the big things were such a bloody mess.

#

Whilst he is the primary focus, this book is not a warts-and-all portrait of Johnson, and it is not a behind-the-scenes look at the machinations of City Hall. There is no secret network of informants that have fed me the real stories behind events, although in most cases the goings-on have been fairly obvious Johnson not being a man particularly good at keeping secrets. Furthermore, a number of journalists, both professional and amateur, tracked his movements from day one and their work has done us all a great service.

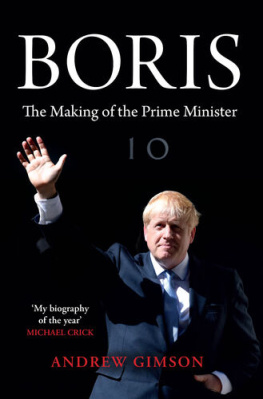

For many, Johnson will be a familiar character, but his back-story is worth recounting, because it shows not only the complexity of the man but also the strange division of the elite that he hails from, and whats more, it tragically helps to shed light on the interpersonal dynamics that have caused so much damage to the country in recent years.

The basic story that is told about Johnson is that he is ambition incarnate, that as a child he wanted to be king of the world, and that he has never wavered from this desire. But for a man seen as such a distillation of Englishness he has a far more inflected and subtle background. He was born on 19th June 1964 in New York, as his father Stanley was at that point a postgrad at Columbia, studying economics. His mother Charlotte is an artist, and Johnson comes from that strange substrata of the ruling class, where underneath the titles and the land a current of bohemianism runs.

His father later worked for the World Bank and the EEC, with a focus on environmental issues, and Johnson spent his early years being shuttled around European schools, before being packed off to Eton. On the one hand it is worth noting that Johnson is not a Shire Tory, coming from a more peripatetic and intellectual background, but his was undoubtedly an ultra-elite beginning, one which raises the intriguing question of whether a similar child would be able to experience that kind of start now, what with the massive rises in fees and the competition from the ultra-wealthy that threatens the clear access the old British elite once had to their educational privilege.

At Eton, Johnson was pals with Charles Spencer (Lady Dianas brother) and Darius Guppy, whose ancestor gave his name to the fish. Johnson was a Kings Scholar, and won prizes in English and Classics, which highlights his oft-doubted intelligence, but this may well have been the high-point of his academic career. It is worthwhile noting the famous culture of popularity that is cultivated at Eton, with privileges often being dependent upon lobbying fellow students, and how that seems to create young men utterly convincing in their insincerity. After a gap year in Australia he went up to Oxford to read Classics at Balliol in 1983, part of a generation of students there at the same time who would go on to dominate British politics former PM David Cameron, former leader of the Tories William Hague, and other long-term colleagues and rivals such as Michael Gove, Jeremy Hunt, and Nick Boles.

Next page