Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publishers nor the author assume any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publishers do not have any control over and do not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

TO LEO F. JOHNSON

INTRODUCTION

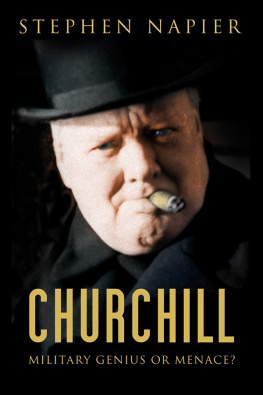

A DOG CALLED CHURCHILL

W hen I was growing up, there was no doubt about it. Churchill was quite the greatest statesman that Britain had ever produced. From a very early age I had a pretty clear idea of what he had done: he had led my country to victory against all the odds and against one of the most disgusting tyrannies the world has seen.

I knew the essentials of his story. My brother Leo and I used to pore over Martin Gilberts biographical Life in Pictures, to the point where we had memorised the captions.

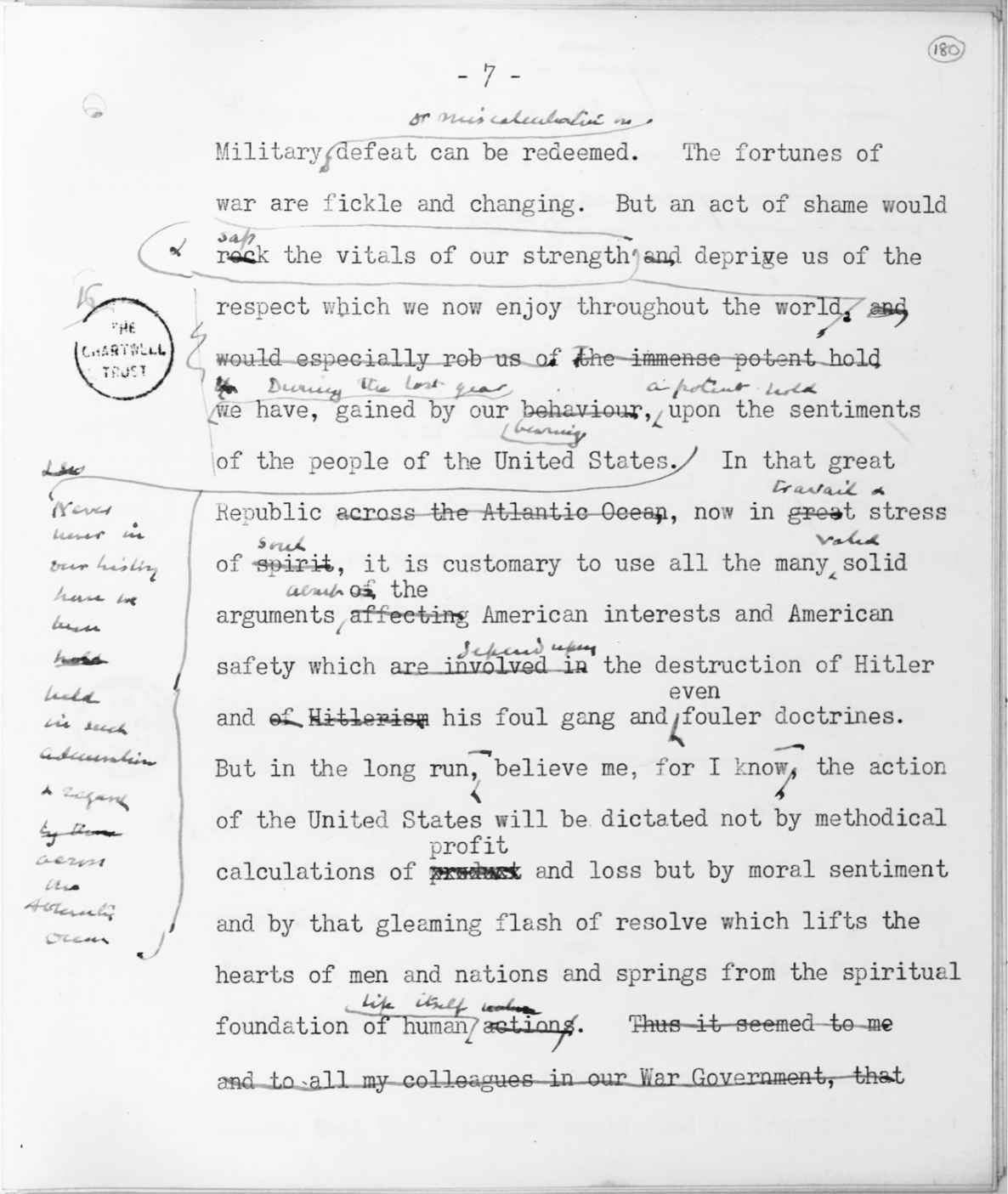

I knew that he had a mastery of the art of speech-making, and my father (like many of our fathers) would recite some of his most famous lines; and I knew, even then, that this art was dying out. I knew that he was funny, and irreverent, and that even by the standards of his time he was politically incorrect.

At suppertime we were told the apocryphal stories: the one where Churchill is on the lavatory, and informed that the Lord Privy Seal wants to see him, and he says that he is sealed in the privy, etc. We knew the one where Socialist MP Bessie Braddock allegedly told him that he was drunk, and he replied, with astonishing rudeness, that she was ugly and he would be sober in the morning.

I think we also dimly knew the one about the Tory minister and the guardsman... You probably know it, but never mind. I had the canonical version the other day from Sir Nicholas Soames, his grandson, over lunch at the Savoy.

Even allowing for Soamess brilliance in storytelling, it has the ring of truthand tells us something about a key theme of this book: the greatness of Churchills heart.

One of his Conservative ministers was a bugger, if you see what I mean... (said Soames, loudly enough for most of the Grill Room to hear)... though he was also a great friend of my grandfather. He was always getting caught, but of course in those days the press werent everywhere, and nobody said anything. One day he pushed his luck because he was caught rogering a Guardsman on a bench in Hyde Park at three in the morningand it was February, by the way.

This was immediately reported to the Chief Whip, who rang Jock Colville, my grandfathers Private Secretary.

Jock, said the Chief Whip, I am afraid I have some very bad news about so-and-so. Its the usual thing, but the press have got it and its bound to come out.

Oh dear, said Colville.

I really think I should come down and tell the Prime Minister in person.

Yes, I suppose you should.

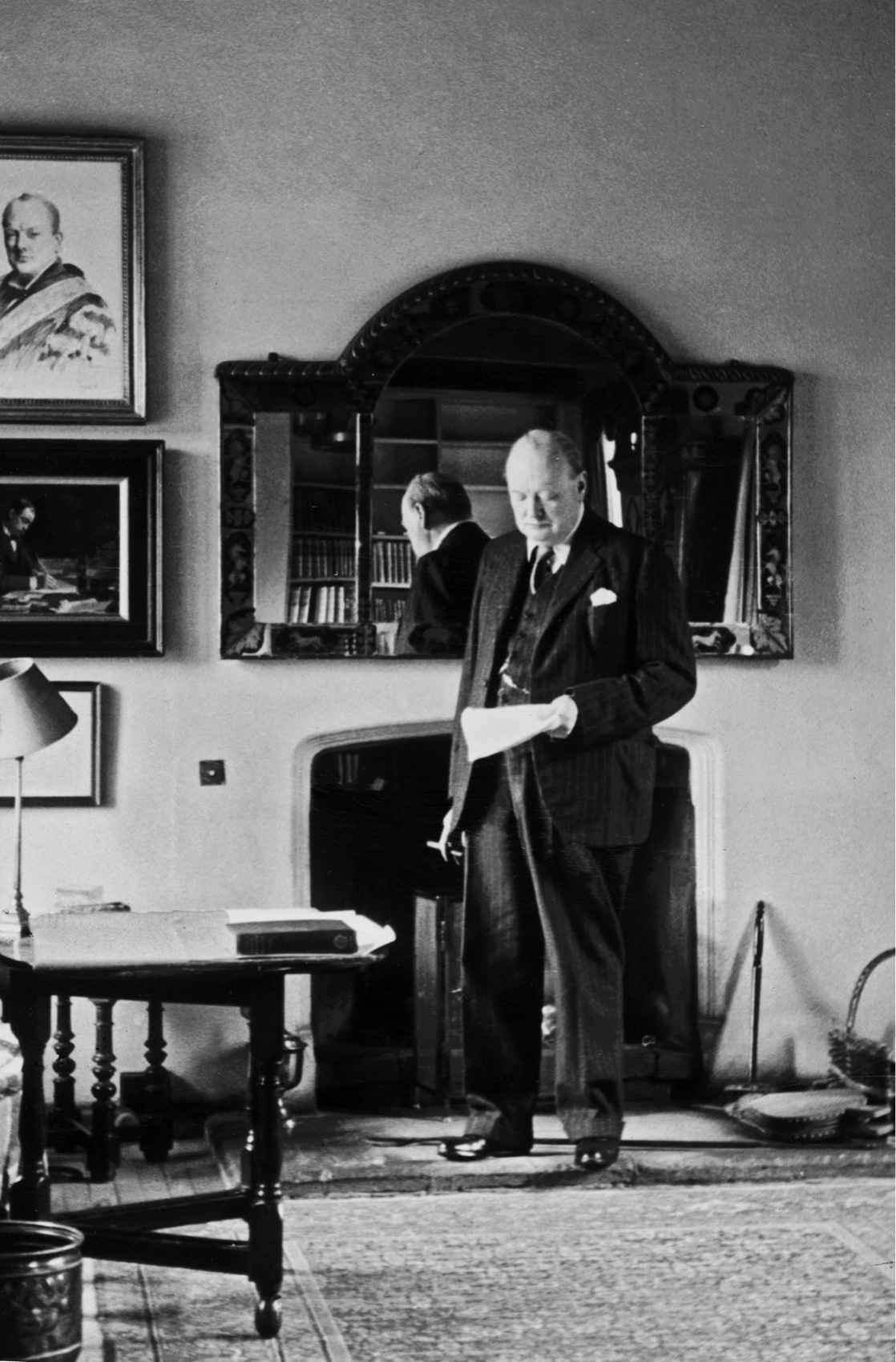

So the Chief Whip came down to Chartwell [Churchills home in Kent], and he walked into my grandfathers study, where he was working at his upright desk. Yes, Chief Whip, he said, half turning round, how can I help you?

The Chief Whip explained the unhappy situation. Hell have to go, he concluded.

There was a long pause, while Churchill puffed his cigar. Then he said: Did I hear you correctly in saying that so-and-so has been caught with a Guardsman?

Yes, Prime Minister.

In Hyde Park?

Yes, Prime Minister.

On a park bench?

Thats right, Prime Minister.

At three oclock in the morning?

Thats correct, Prime Minister.

In this weather! Good God, man, it makes you proud to be British!

I KNEW THAT he had been amazingly brave as a young man, and that he had killed men with his own hand, and been fired at on four continents, and that he was one of the first men to go up in an aeroplane. I knew that he had been a bit of a runt at Harrow, and that he was only about 5 feet 7 and with a 31-inch chest, and that he had overcome his stammer and his depression and his appalling father to become the greatest living Englishman.

I gathered that there was something holy and magical about him, because my grandparents kept the front page of the Daily Express from the day he died, at the age of ninety. I was pleased to have been born a year before: the more I read about him, the more proud I was to have been alive when he was alive. So it seems all the more sad and strange that todaynearly fifty years after he diedhe is in danger of being forgotten, or at least imperfectly remembered.

The other day I was buying a cigar at an airport in a Middle Eastern country that had probably been designed by Churchill. I noticed that the cigar was called a San Antonio Churchill, and I asked the vendor at the Duty-Free whether he knew who Churchill was. He read the name carefully and I pronounced it for him.

Shursheel? he said, looking blank.

In the war, I said, the Second World War.

Then he looked as though the dimmest, faintest bell was clanking at the back of his memory.

An old leader? he asked. Yes, maybe, I think. I dont know. He shrugged.

Well, he is doing no worse than many kids today. Those who pay attention in class are under the impression that he was the guy who fought Hitler to rescue the Jews. But most young peopleaccording to a recent surveythink that Churchill is the dog in a British insurance advertisement.

That strikes me as a shame, because he is so obviously a character that should appeal to young people today. He was eccentric, over the top, camp, with his own special trademark clothesand a thoroughgoing genius.

I want to try to convey some of that genius to those who might not be fully conscious of it, or who have forgotten itand I am of course aware that this is a bit of a cheek.

I am not a professional historian, and as a politician I am not worthy to loose the latchet of his shoes, or even the shoes of Roy Jenkins, who did a superb one-volume biography; and as a student of Churchill I sit at the feet of Martin Gilbert, Andrew Roberts, Max Hastings, Richard Toye and many others.