I t was in August 2008 that I first experienced Latinate evasion; I had no idea what it was at the time. I didnt find out until more than ten years later while researching this book. According to this technique, if you are backed into a corner and called upon to give a straight answer, there is a way out: give a Latin veneer to your response and people will be so impressed or bedazzled that they wont notice that you have both given and withheld an answer at one and the same time.

Most wont even know what you are talking about until later, when they have googled it, which is the position I was in after an interview at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing. I was reporting on Prime Minister Gordon Browns visit, but Boris Johnson stole the headlines as the newly elected Mayor of London, mainly with his startling speech marking London as the host of the next Games.

Wiff-waff was coming home, he declared, stating that the Chinese national sport of ping-pong was invented in England by the Victorians. I was in the audience and saw the collective jaws of the dignitaries alongside him hit vi the floor in astonishment that anyone, especially a relative political novice, could be so irreverent on such a grand occasion and carry it off.

The Latinate evasion came twenty-four hours earlier, when I interviewed Johnson at the Games. With his Old Etonian rival David Cameron yet to make his mark as Tory leader, the obvious way to skewer the new mayor was to ask if his sights were now set on the Conservative leadership.

After playfully dodging the question once or twice, Johnson muttered: Were I to be pulled like Cincinnatus from my plough, it would be a great privilege and sauntered off.

Come again?

After getting a wifi connection I learned that Cincinnatus was a Roman statesman of great virtue who had given up public life but returned from his farm to save Rome from invasion. The denarius dropped: Boris did want to oust Dave. I had my story. But Johnson had couched his disloyalty in such heroic lyricism it made you want to smile, not scowl; to admire his ambition and erudition, not admonish him. It appears he learned this device from one of his Tory idols, Alan Clark, a minister in Margaret Thatchers government.

It is not hard to see why Johnson might identify with right-wing intellectual Clark, who was notorious for calling Africa Bongo Bongo Land and parading affairs with the wife of a judge and her two daughters, whom he referred to as the coven. But what struck Johnson vii most was Clarks response when he was caught lying in the 1990s arms-to-Iraq weapons scandal. When asked in court if he had told the truth, Clark drawled that he had been economical with the actualit.

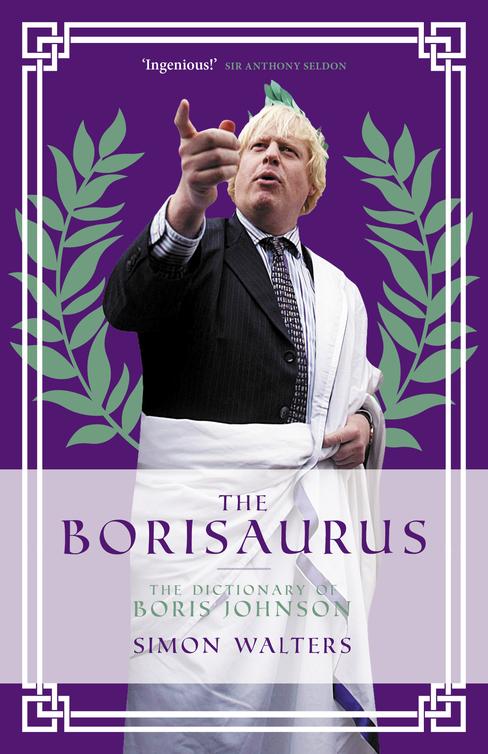

It wasnt just brilliant, concluded Johnson, speaking at a Latin-themed charity event in 2007; it was also less self-condemnatory than I lied. The thing about Latinate words is theyre evasive. Eureka.

Classicist Johnsons articles, speeches, books and interviews are full of the lexicon and imagery of gods, myths, battles and epic poems adapted for schoolboy puns and scholarly polemics. They are also full of German, Norse, Yiddish and many other languages, to inform and entertain as well as to get him out of a tight corner. It is hard not to be impressed by the vast cultural hinterland he flaunts; his range of voices, from Archimedes to Alf Garnett, Suetonius to the Stones, grandiloquent prose and grimace-inducing wordplays delivered together on great occasions.

One minute he is Billy Bunter, all cripes and crumbs; the next, Mary Beard retracing the Battle of Cannae; then it is a cod Churchill, replacing the V for victory with a walrus-like, flapping Benny Hill salute. Next it is Jeremy Clarkson on Viagra bellowing over the roar of an MG roadster. In one bound he can leap from Gussie Fink-Nottle to a Keef Richards riff; adolescent to academic, philosopher to fool without pausing for breath.

An article about motoring speed limits contains what viii seems like an innocuous reference to a Ferrari Testadicazzo. Not being familiar with that model nor an Italian speaker I checked. The result is outrageous: you will find it in this book under T.

The impact of Johnsons controversial statements is often heightened by masking them with a miasma of faux ignorance, as one commentator put it. He gains the attention of those with little interest in politics by inviting them to laugh at him playing the buffoon because they can see that underneath it, he isnt one. He calls it imbecilio (another favourite Latin word).

Latinate evasion hasnt always got him off the hook. When the story of his affair with Petronella Wyatt broke in 2004, I was the political journalist who asked him if it was true. His reply, dismissing it as an inverted pyramid of piffle, will live for ever as the original Borisism.

It may have been brilliant, but it was also a lie. He was fired from the Tory front bench as a result. Johnson looked on the bright side: There are no disasters, only opportunities. And, indeed, opportunities for fresh disasters.

The range, roots, richness and rudery of the nouns, verbs and adjectives at his command is spellbinding. When he cant find the right word, he makes one up.

If you constructed a giant word map based on Johnsons writings, among the names of Homer, Pericles, Caesar, Antony and Cleopatra, Thatcher, Bush, Blair, Brown, Delors, Trump, Cameron, May, Corbyn and Heseltine, there would be all manner of descriptions ix of breasts, male virility and sex in general. Listen to his defiant tribute to Dr Samuel Johnson, who produced one of the first English dictionaries: a slobbering, sexist xenophobe who understood human nature; a man who, despite his flobbery lips, had such natural charisma that women fought to sit next to him; a brilliant champion of the English language and the little guy. Which Johnson does he have in mind?

Some of his earlier work (in particular his novel, the unsubtly titled Seventy-Two Virgins) is shocking when reviewed in the third decade of the twenty-first century. Parts seem like an excuse for the racist and sexist outpourings you might expect from the 1970s teenage public schoolboy he once was, except it was written in 2004, when he was entering his forties and had been an MP for three years. The word coon appears gratuitously six times within a few sentences admittedly as part of the dialogue, not, strictly speaking, the voice of the narrator; but there is no mistaking it as coming from a place of authenticity. It is the same streak that made him dare to joke about Muslim women with letter-box veils resembling bank robbers less than a year before he became Prime Minister.

Other words and phrases reveal deeper thoughts about ambition, Islam, public and private morals, journalism, blood sports, climate change, the old and the young. Not forgetting Europe; lots of Europe. Very little on economics. Some of his views have stayed the same; x with others he has done a handbrake turn worthy of one of his car reviews.

The same Boris who, soon after becoming Prime Minister, told a sceptical senior banker that his economic strategy is based on boosterism scoffed at another fresh new Prime Minister for taking the same approach in 1997. The understated, tongue-tied self-effacement of boring John Major was what foreigners loved most about Britain, wrote Johnson, not flashy Tony Blairs loutish boosterism.

The animal rights crusader who howled in 2018 that you would have to be crapulous (sickeningly drunk) to fail to protest about Japanese whaling doubtless earning the approval of partner Carrie Symonds, who works for environmental organisation Oceana eulogised the gralloching (disembowelling) of a stag a decade earlier. The man who now says he will ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars to curb the risk of climate change flooding lampooned eco-warriors in 2000 for suggesting vehicle emissions were as he put it turning the outskirts of Taunton into the Brahmaputra delta [the Bangladesh flood zone].