A mong the scores of people who kindly agreed to be interviewed for this book, many asked not to be named publicly. For this reason, it is not possible to identify here everybody who deserves thanks; suffice it to say that without their input this project would not have been possible. For ease of reference, it should be assumed that unless otherwise attributed all quotes are taken from interviews conducted for this book between July 2021 and February 2022.

Several people who are happy to be recognised for their efforts were notably generous with their time and help. Margaret Crick, Michael Crick, Mark Hookham, Sallie Salvidant, Cerys Turner and David Wharton all assisted and advised in different and important ways.

Thanks must also go to the formidable Angela Entwistle and her team, as well as those at Biteback Publishing who were involved in the production of this book. And special thanks to my chief researcher, Miles Goslett.

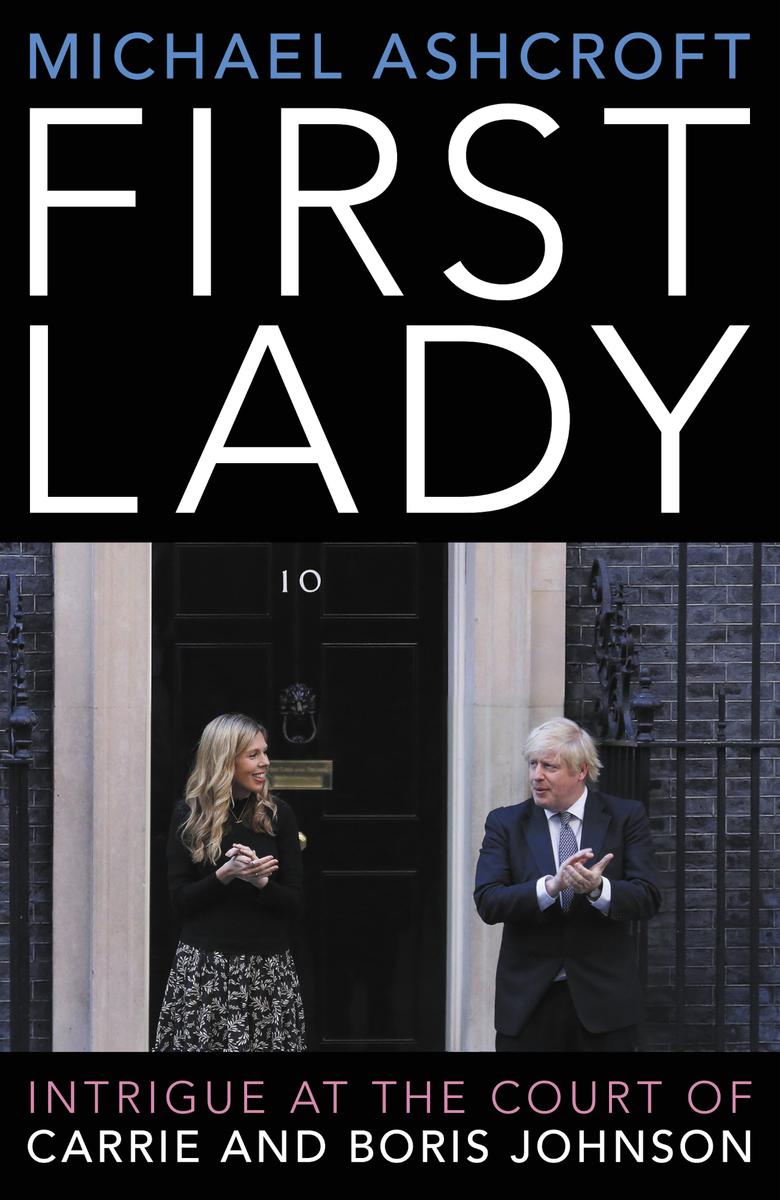

O n 24 July 2019, Carrie Symonds entered Downing Street as the first unmarried partner of a Prime Minister in British history. She was thirty-one years old and she was the girlfriend of one of the most polarising politicians to take the highest office in the land, Boris Johnson.

There is no question that becoming the prime ministerial consort, a job for which there is no official description, would be daunting for anybody regardless of their age or the identity of their partner. What might have made the situation for Carrie harder still is that most people who had heard of her in July 2019 probably knew only that she had been named as the young lady who had been accused of being at the centre of Johnsons divorce from his second wife, Marina; or that there had been a domestic dispute involving Johnson at her flat in London the previous month to which the police had been called. To have attracted the attention of the press for such matters before even crossing the threshold of No. 10 must have been unsettling. xiv

What made the circumstances under which Carrie set up home in Downing Street even more unusual was that, thanks to her being a former employee of the Conservative Party and an ex-government special adviser, she was also the first consort of any Prime Minister to be part of what is known as the Westminster bubble the insular world of Lobby journalists, politicians and aides whose lives are centred around Westminster and Whitehall. Some journalists concluded that her professional background made her a political figure in her own right. Again, this set her apart from previous consorts.

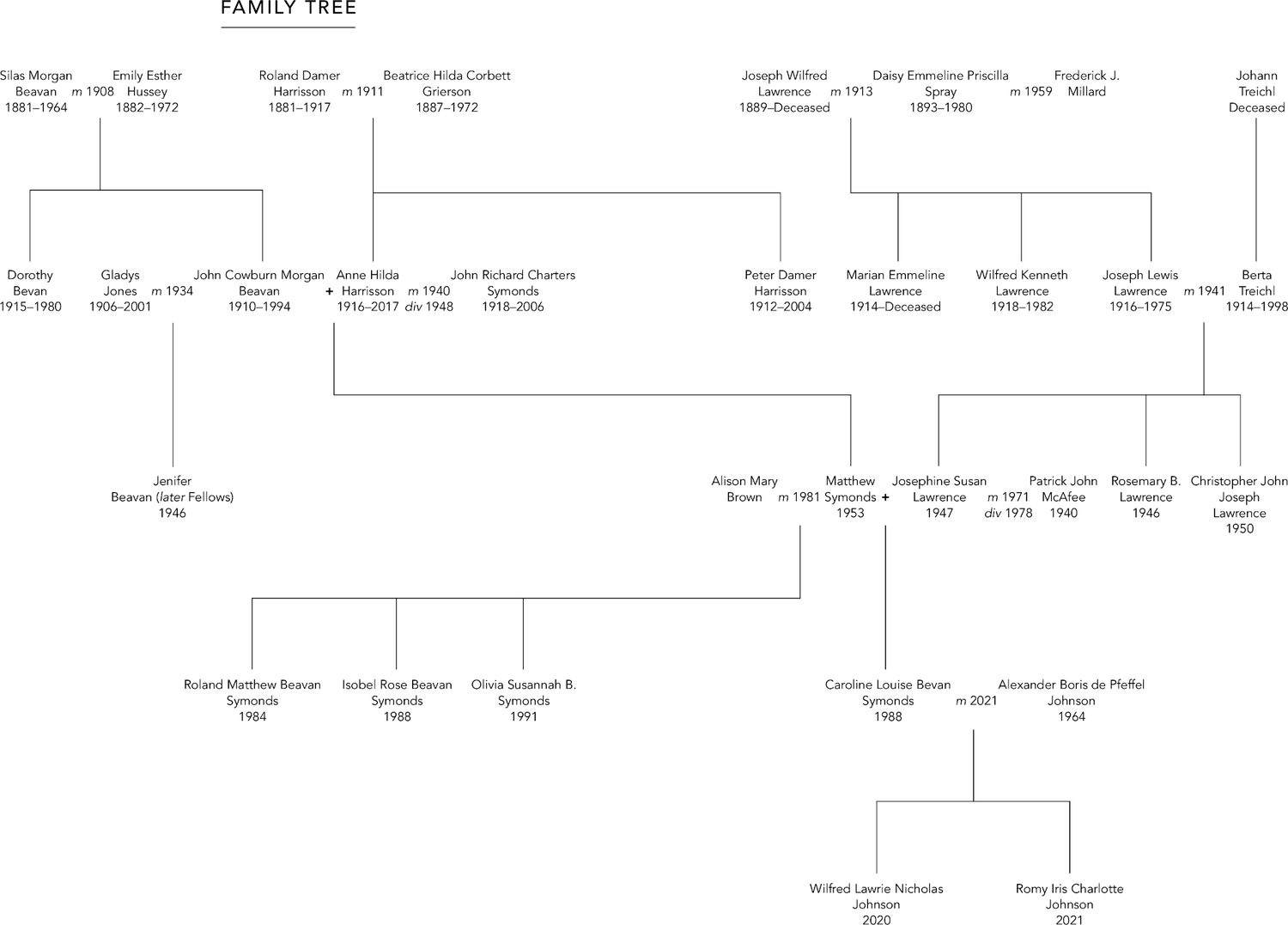

Politics and power are in Carries bloodline. As her rather complicated but very colourful family tree shows, her great-grandmother Hilda Harrisson and her grandfather John Beavan also had close friendships with Prime Ministers of their respective eras. Indeed, in the 1970s, Beavan sat as a Labour member of the House of Lords and later went to Brussels as one of Britains first MEPs. Furthermore, Carries father, Matthew Symonds, became a man of public standing in the 1980s when he helped to found a national newspaper, The Independent.

Perhaps it should come as no surprise, then, that since 2019, Carrie has come to be thought of by many people in Westminster and beyond as influential herself, especially in the areas of policy and patronage. Power ought to come with accountability. This book addresses a series of events which have dominated Boris Johnsons premiership to date and puts these claims about his now-wife to the test. Often, what I heard about Carrie while working on this project surprised me a great deal. Readers must judge for themselves, however, what her behaviour in a political context says xv about her relationship with Boris Johnson and what this has meant for the way Britain has been run under him.

Officially, there is no such thing as a First Lady in British politics. This title tends to be associated by most people with the wife of the American President. Yet in the case of Carrie Johnson, as she has been since May 2021, it does not seem entirely out of place that some have ascribed it to her as well. For while it is true that she regards herself as a private individual with no formal role in public life, she has shown a remarkable ambition compared with most, if not all, of her predecessors. This book explores just how far-reaching that ambition has become.

Michael Ashcroft

February 2022

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

I have chosen to refer to Carrie Johnson as Carrie throughout this book. Partly this is to avoid confusion because she changed her surname from Symonds to her married name, Johnson, in May 2021, and much of the text covers her life and career before that date. Using just her Christian name also differentiates her from her husband, Boris Johnson, who is referred to in narrative sections by his surname.

H istory has a habit of repeating itself or, perhaps more accurately, patterns emerge. An assessment of Carrie Johnsons family tree certainly appears to support this conclusion. For although she learned long ago that she came into the world as a result of an extramarital affair, any unease this has brought her should have been ameliorated to some degree by the certainty that she is only following in the footsteps of at least one and potentially two direct relations who were born in similar circumstances: her father, Matthew Symonds; and her grandmother, Anne Symonds. Both rose to success in their chosen field of journalism. Intriguingly, two other forebears, her great-grandmother Hilda Harrisson and her grandfather John Beavan, enjoyed close friendships with Prime Ministers of their day, with Beavan managing to secure a measure of political influence that is beyond the reach of most people. If illegitimacy is in Mrs Johnsons bloodline, therefore, so, arguably, are the arts of journalism and politics, whose ingredients have been so essential to her own career and, ultimately, to her adult life to date. When all of this is considered, maybe the only surprising thing about her now living in Downing Street as the Prime Ministers wife and arguably the most powerful unelected woman in the United Kingdom after the Queen is that anybody is surprised by this at all.

The facts behind Carrie Johnsons origins are undeniably absorbing, but they are also somewhat tangled. She was born Caroline Symonds at Queen Marys Hospital in Roehampton, south-west London, on 17 March 1988. Yet, as will become clear, the surname Symonds, which she inherited from her father and which she used prior to her marriage to Boris Johnson in May 2021, was not rightfully her fathers to bestow according to tradition or convention. By extension, neither, arguably, should it have been hers. Unlocking the explanation of how she came to have the Symonds name can only be achieved by first examining the lineage of her father, whose own upbringing was also complicated by marital infidelity, just as Carries would be.

Matthew Symonds was born in 1953, the son of Anne Symonds, a divorced BBC broadcaster, and John Beavan, a well-connected left-wing newspaper journalist who was married to another woman, Gladys Jones. Beavan, Carries grandfather, was born in the Ardwick district of Manchester in 1910, the product of a staunchly Labour family, and baptised at the Primitive Methodist Chapel there. His father, Silas, who was Carries great-grandfather, was born in Hay, in Wales, in 1881 and worked as a miner before becoming a greengrocer in the Manchester area; his mother, Emily, who was Carries great-grandmother, was born in 1882 and is said to have been an exceptionally strong character. She rose from humble origins to become a Manchester City councillor, justice of the peace, alderman and womens rights campaigner. She was once in contention to become Manchesters Lord Mayor, but her husbands poor health forced her to decline this opportunity. Her career is commemorated in Openshaw, just outside Manchester, where the street Emily Beavan Close is named in her honour.

xi

xi