Getting Inside Your Head

What Cognitive Science Can Tell Us about Popular Culture

LISA ZUNSHINE

2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2012

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zunshine, Lisa.

Getting inside your head : what cognitive science can tell us about popular culture / Lisa Zunshine.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4214-0616-9 (hdbk. : acid-free paper) ISBN 1-4214-0616-0 (hdbk. : acid-free paper)

1. Psychology and literature. 2. Cognition and culture. 3. Popular culture and literature. 4. Characters and characteristics in literature. 5. Philosophy and cognitive science. I. Title.

PN 56.P93 Z 86 2012

801.92dc23 2011048290

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

But what was to be done about the impossibility of seeing into other peoples souls?

Ellen Spolsky, Word vs Image

Contents

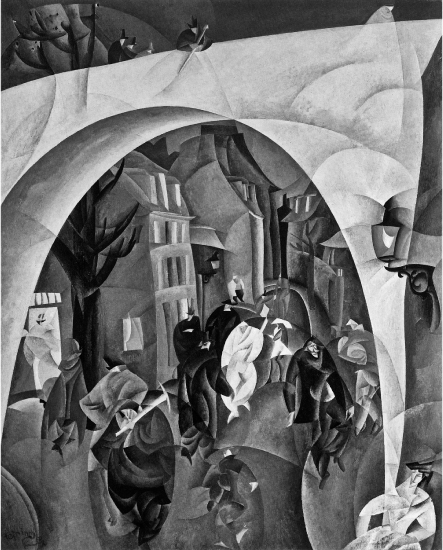

Illustrations

Preface: Fantasies of Access

In which Bart Simpson is thinking; Mona Lisa is smiling; the purpose of this book is revealed; its genre is canvassed; and a long-due gratitude is expressed.

We live in other peoples heads: avidly, reluctantly, consciously, unawares, mistakenly, inescapably. Our social life is a constant negotiation among what we think we know about each others thoughts and feelings, what we want each other to think we know, and what we would dearly love to know but dont.

Weve been doing this for hundreds of thousands of years. Cognitive scientists have a special term for the evolved cognitive adaptation that makes us attribute mental states to ourselves and to other people; they call it theory of mind or mind reading. Though it may sound like telepathy, theory of mind is actually its opposite. Telepathy implies perfect self-conscious access to someones thinking. Mind reading is approximate guessing and imperfect interpretation, most of it taking place below the radar of our consciousness.

Our culture is both a product of theory of mind and its stomping ground. We enter it by attributing mental states to everybody from Bart Simpson to Plato and from Mona Lisa to the drafters of the U.S. Constitution. Cultural representations, high and low, exploit the fact that we live in other peoples heads yet have no direct access to their thoughts and feelings. Novels, movies, paintings, and situation comedies all build on theory of mind, experiment with it, and feed it elaborate social fantasies.

One such fantasy is the fantasy of perfect access to mind through body. We get to see fictional characters at the exact moment when their body language betrays their real feelings. This is in contrast to real life, in which there is always a possibility that we will misinterpret seemingly transparent body language, particularly in a complex social situation, or that people will perform transparent body language to influence our perception of their mental states.

The fantasy of perfect access to mind through body is old, but it takes surprising new forms in different historical periods and genres: thirteenth-century Chinese operas; medieval ribald tales; eighteenth-century French paintings; nineteenth-century English novels; twentieth-century movies, musicals, photography, and stand-up comedy; and twenty-first century reality television. This book is about how this fantasy works, when it stops working, and why we cant get enough of it.

Though dealing with novels, film, and art, this is neither literary or film criticism nor art history. I dont offer a comprehensive analysis of a particular writer, movie, painting, genre, or motif, and I steer clear of specialized vocabulary. Most works under discussion have been extensively analyzed by others. Whenever I can, I happily point to instances of compatibility with existing studies, but, fruitful as I believe it to be, a sustained exploration of such compatibility is beyond the scope of this project. Pressed for the genre of what I do here, I would call it cognitive cultural studies, though I think of it mainly as a book-length thought experiment: an attempt to view a variety of cultural phenomena from one particular perspective made possible by research in cognitive science and to push that perspective as far as possible.

Writing up this thought experiment took five years and as many drafts, and I have incurred many intellectual debts along the way. As always, I found support and inspiration among the community of scholars working with cognitive approaches to literature and culture: Porter Abbott, Frederick Luis Aldama, Mike S. Austin, Elaine Auyoung, Joseph Bizup, Mary Crane, Nancy Easterlin, William Flesch, Monika Fludernik, F. Elizabeth Hart, David Herman, Patrick Colm Hogan, Tony Jackson, Suzanne Keen, Jonathan Kramnick, Howard Mancing, Bruce McConachie, Alan Palmer, Isabel Jan Portillo, Alan Richardson, Elaine Scarry, Vernon Shetley, Ellen Spolsky, Gabrielle Starr, Simon Stern, and Blakey Vermeule.

I am grateful to the Guggenheim Foundation and to the University of Kentucky College of Arts and Sciences, whose generous support enabled me to spend a year and a half as a visiting scholar at the Yale Department of Psychology; to Paul Bloom, who made that magical year possible by inviting me to his Mind and Development Lab and who helped me realize the importance of restraint for embodied transparency; to the affiliates of his lab, particularly Mark Sheskin, for his valuable insights about Stephen Sondheim; to the members of the Mind, Brain, Culture, and Consciousness group at the Whitney Humanities Center at Yale; to Michael Holquist, Doug Whalen, Philip Rubin, Ken Pugh, and other members of the Teagle-Haskins Collegium; to Kang-i Sun Chang, for her generous help with the Chinese opera; to Stephen Kern for his similarly generous assistance with proposal compositions; to Evelyn Birge Vitz, whose inspiring approach to performance turned me to embodied transparency in medieval literature; to James Phelan, for his crucial early advice about transparent bodies and narrative; to Ralph James Savarese for introducing me to disability studies sensitive to the possibilities opened by the autistic view of the world, as opposed to just its limitations, and for stepping in at the last moment to correct relevant parts of my argument; and to Jason Flahardy at the University of Kentucky Special Collections and Kathryn Wong Rutledge and Mary Lou Cahal from the University of Kentucky Teaching Academic Support Center for their invaluable work on illustrations.

At the Johns Hopkins University Press I am grateful to Trevor Lipscombe, Matt McAdam, and Deborah Bors. I also thank my copyeditor Joe Abbott, and, most important, the anonymous reader whose comments made me revise large portions of the book.

Next page