Table of Contents

Guide

W HENEVER A WOMAN DOES ANYTHINGWRITE A BOOK , create a life, have a careerthe labor is often manifold and doesnt come with a break from laundry, homework, floor scrubbing, or cooking. During the course of writing this book, my whole life changed. I went from being married to being a single mom. But I still had kids. I still had dirty floors. Sometimes this was a blessing, often it was overwhelming as hell.

So many of my friends stepped in to help me with childcare, house cleaning, meal preparation, moving, furniture assembly, and so much more. They were the women of my community cheering me on. Offering me support, advice, book recommendations, sending me articles, giving me feedback, mailing me sassy socks, sending me kind texts and direct messages. Always with their loving and generous spirits, even when I was too overwhelmed to say thank you.

They are my true church of the airthe community of women throughout the internet and in my town, without whom this book would not be. Without whom I would not be. Some of their names are Melanie Ostmo, Kristin Engle, Jeanne Towell, Yara Conway, Jessie Lowe, Megan Sova-Tower, Claire Zulkey, and all the witches.

I also want to thank my agent, Saba Sulaiman, who believed in my writing when no one else did. Ashley Runyon, who saw a book inside an internet article. And Ted Scheinman, an amazing and thoughtful editor, whose feedback, friendship, wisdom, and prompt responses to my pitches not only gave me a platform for my first thoughts on this subject, but also gave my words a home.

I also want to thank all the people who talked to me for this project, especially Mark Jackel-Juleen, who put me on the right course, and Evelyn Birkby, whose insight, generosity, and gift of time was foundational to my work.

Thanks to Pastor Ritva, who has never once asked me to work in a nursery.

My brother Zach is my best friend, and even though I still maintain he is the worst, he is also the best. His encouragement and terrible jokes have helped my words and my story find life. And all of my siblings, who taught me that we can all touch the same truth and walk away with different answers. And my parents, who raised me with love, God, and books and have always had my back even when Ive sold them out on the page.

My friends Elon Green, Sarah Weinman, Nicole Cliffe, and Sarah Galo. You know what you did. Also, Marisa Seigel, Pam Colloff, Amy Sullivan, Kate Bowler, Deborah Jian Lee, Kathy Khang, Katelyn Beaty, Laura Turner, and Julie Rogers. And of course, Katie Bukowski, Anna Marsh, and Kate Johansen.

And of course to my children, Jude and Ellis, who are the most incredible human beings Ive ever met.

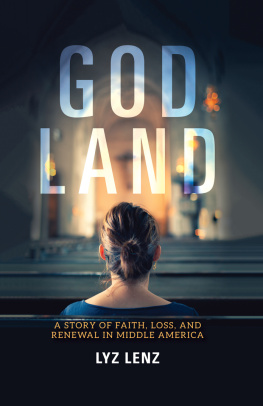

LYZ LENZ has been published in the New York Times, BuzzFeed, the Washington Post, The Guardian, ESPN, Marie Claire, Mashable, Salon, and others. Her book Belabored: Tales of Myth, Medicine, and Motherhood is forthcoming from Norton. She also has an essay in the anthology Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape Culture edited by Roxane Gay. Lenz holds an MFA in creative writing from Lesley University and is a contributing writer to the Columbia Journalism Review.

W HEN I WONDER ABOUT WHERE THE CRACKS IN everything began, I go back to Stonebridge. Stonebridge was a church that my husband and I and six other friends tried to start in Marion, Iowa, in 2010. We were all frustrated with what we saw as faith in America. We were frustrated with faith in our town. And in the beginning, we were united in our grievances. In our estimation, the churches did little for the town. They had loud brassy bands and hip pastors, but no substance. There was no community. And everyone always looked the same. There had to be another way, and so we decided to make something for ourselves.

Its a very colonizing impulse to look at somethinga land, a city, a cultureand instead of seeing what is there, see a barren landscape that needs your new ideas. Its an American impulse to see a problem and think you can solve it with a little hard work and some bootstraps. Its a deeply human impulse to look all around you and see a problem but never consider that you might be the actual problem. If we had, for a moment, pondered the logic of any one of our impulses, everything might have turned out differently. But we didnt. And so, we got into a mess.

The problem we saw that we wanted to solve was this: In our state there were anemic rural churches that lacked vibrancy. And vibrant city churches that lacked depth. We would change all of that. Wed build something small but robust. Something holy and relevant. Something meaningful and practical. Reading over our notes from those meetings feels a lot like asking a twenty-year-old man what he wants in a woman and hearing him say, I want her to be outgoing, but also likes a night in. I want someone who likes to have fun, but will also cook a three-course meal. A lover and a mother. A simple woman, who has class and taste. Who loves to save money, but does all the shopping. In sum, we didnt know what the hell we wanted. But we thought we did. And at least we knew we didnt want any of the other places wed been to.

Since moving to Cedar Rapids in 2005, Dave and I had attended almost twenty churches. One church we went to never invited us into a Bible study. When I asked a pastor or a Sunday school teacher about Wednesday night Bible studies, I was always told to ask someone else, who told me to ask someone else. This went on for five months, until one Sunday the pastor preached a sermon about the importance of small groups and said from the pulpit that all we had to do was ask to be invited. We never went back.

Or there was the church we visited in 2006 that sent three teams of elders to prayer walk around our townhouse. I sent them packing after I opened the door and asked them what they were doing. Can we speak to your mom? asked one of the older gentlemen in a suit and a tie.

I am the mom, I said and slammed the door shut. They left a flyer under the door and walked around our townhouse praying once more, for good measure.

There was the church we visited in 2005, where we heard several sermons about not jumping ship when your church goes bad. The bad was vague and never specified. Needless to say, we did not go back there either.

After three years of searching, Dave and I finally ended up at an Evangelical Free Church. It was there we met the couples we started Stonebridge with and got involved with the youth group. But even then, that church wasnt an easy fit for us. Or, I should be clear, it wasnt an easy fit for me. The church was a lot like the Evangelical churches Dave and I had attended as kidsraucous music, a pastor who gave sermons that often included video clips and pop-culture references. There was no liturgy, there were no organs, and most of the people who attended seemed to be our age. Few people drank, no one smoked, and they all loved to discuss the book of Revelation after one too many Mountain Dews at a church party.

While I loved the people there, I didnt like the churchs theology. The church was and is very conservative; their theology was that of the Evangelical Free Church of America, which doesnt affirm women or gay people as pastors or elders. Here strict gender roles were enforced and even seen as freeing. Everybody was white.

As someone who doesnt like to wear bras on principle, I frequently found myself chafing against the strict orthodox interpretation of the Bible and the long lectures I was often given by male members of the church about how, if I believed women could be pastors, I was questioning the inerrancy of the Bible.

But in those early days of my marriage and my adult life, I thought that these problems were minor squabbles. Something to be hashed out over late nights playing board games and drinking wine, or wine for me, Fresca for the rest of them. It was a privilege, born of my childhood raised in a white Evangelical homeschool subculture in Texas. Until I went to high school at a public school, everyone I knew believed in a literal six-day creation by the hand and voice of God. Everyone believed that being gay was a sin. I was used to being the outsiderthe lone voice of dissent. I was comfortable with this role because I wasnt threatened by it. Not yet, anyway. I wasnt gay. I wasnt a person of color. I was a woman, but the gentle grasp of patriarchy hadnt yet threatened to strangle me, because I hadnt yet tried to get free. Or perhaps I had, but I was so used to a religion that told me I was wrong and objectionable, it never occurred to me there could be another way.

Next page