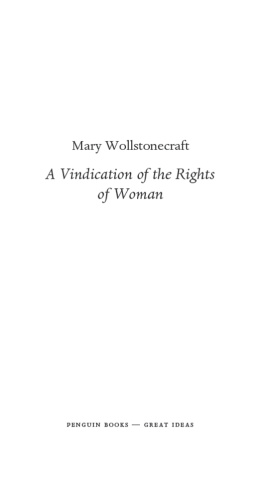

Lyz Lenz - Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women

Here you can read online Lyz Lenz - Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: PublicAffairs, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lyz Lenz: author's other books

Who wrote Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 2020 by Lyz Lenz

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover copyright 2020 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

This is a work of creative nonfiction. While the events are true, they reflect the authors recollections of experiences over time. Additionally, some names and identifying details have been changed, and some conversations have been reconstructed.

A portion of Context originally appeared in The Rumpus (Writing My Context, 2016) and appears here courtesy of The Rumpus.

A portion of Miscarriage originally appeared in Jezebel (Why Are We So Paranoid about What Pregnant Women See?, 2016) and appears here courtesy of Jezebel.

Bold Type Books

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor New York, NY 10003

www.boldtypebooks.org

@BoldTypeBooks

First Edition: August 2020

Published by Bold Type Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. Bold Type Books is a co-publishing venture of the Type Media Center and Perseus Books.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020001916

ISBNs: 978-1-5417-6283-1 (hardcover); 978-1-5417-6282-4 (ebook)

E3-20200709-JV-NF-ORI

To my children, who ripped up my vulva on their way into the world.

In a poem attributed to Herbert Farnham, a mother is described as a flower, majestic as a tree, gentle as the dew, calm as the quiet sea. She is as graceful as a bird and as beautiful as twilight. God, Farnham wrote, pulled all these elements together and called them simply Mother.

I read Farnhams poem on a card that I received from my mother-in-law on my first Mothers Day in 2011. I was still sixty pounds over my pre-baby weight and constipated from the iron pills I had to take because I lost so much blood during labor. Every time I went to the bathroom, my bowel movement pressed against my stitches and made me cry. The only thing dewy about me was the noxious stew of postpartum juices in my underwear. My vagina looked like raw ground beef.

I tossed that card and all its treacle in the trash. What did those words mean, anyway? Dew, sea, brook, flight. None of them had any relation to my life as a mother. The fragrance of the flower had nothing to do with the deep darkness into which I stumbled every three hours each night to stuff my bleeding nipple into a screaming baby. With the way my boobs, once A cups and now E cups, hung like balloons full of sand from my body. The rippling brook sounded nothing like the womp womp womp of the breast pump, which in my exhaustion-induced hallucinations I thought was saying, Bob Hope, Bob Hope, Bob Hope, over and over. The majesty of the tree spoke to no part of my hormonal acne or the way Id stare out the front door and imagine myself running away.

How does it feel to be a mom? my own mother had asked me.

Like myself, but fatter and more tired and with weird shit coming out of my vagina, I said.

My mom has eight children. By the time she was the age I was when my daughter was born, she was already five kids deep. I dont think shed forgotten what it felt like to be in my position. But she had done it all alone. Her own mother absent. My father working all the time. The burning pain of mastitis, the exhaustion, the times she must have sobbed in the bathroom because we wouldnt stop cryingit all had to be for something more than our fat upper pubic area.

A video from 2014 that went viral shows clips of job interviews for a position called Director of Operations. The applicants are told the job involves long hours, no pay, no sitting, no breaks and requires expertise in the culinary arts, medicine, and finance. The job, they are told at the end of the interview, is Mom.

The video, titled #WorldsToughestJob, has been viewed over twenty-eight million times. It is meant to be a celebration of motherhood. Of the pain and the struggle. A glorification of the brutalization of our bodies and the lack of help we get from our own partners and government. It says to women that this, this is the greatest thing you can be: a martyr, a mother.

The pedestal on top of which sits the perfect mother appears in our creation myths. There is Gaia, Mother Earth from Greek mythology, who bore the powerful monstrous children of the god Uranus, the Titans. An Algonquian legend tells of the Mother of Life, who feeds plants, animals, and humans at her bosom. The Inca mythology includes Mama Pacha, fertility goddess of planting and harvesting. Christians have Eve, who failed in her first tasknot to eatand was given a second: bear children. Each creation story ties together the concepts of the worldly and the otherworldly. The flesh and the myth.

Not all creation stories begin with a mother. Not all of them involve a womans body given up for the good ofas its often phrasedmankind. But in America, to be a mother is to become a myth. To be a mother is to step into a role of someone elses invention, to cosplay a character who exists at the intersection of race, class, gender, and religion. Stepping into this role, a woman is no longer a human. (But then, was she ever truly seen as human?) She is now a river, she is dew, she is a majestic tree, she is earth and wind and magic and mama.

But not all mothers are permitted to embody this hallowed, all-consuming role. And who our culture sees as not succeeding in the role of mother says even more about how we conceive of mothers, than who we laud as perfect exemplars.

In our cultural imagination the perfect mother is a white, middle-class, straight, cisgender, married woman. She announces her pregnancy on social media with a photo in which shes smiling, draped in a gauzy dress, framing an almost nonexistent bump with her hands, wedding band glinting in the light. We are happy for her. We say, Congrats, over and over in the comments. Her hair is perfectly curled. Her husband smiles benignly behind her. She is the modern-day Virgin Mary.

This mother doesnt force us to think of the complications of sperm and egg. With the focus on her glowing skin and hair, we get to skip that part. The perfect mother would never force us to think about sex.

Imagine if that woman had conceived before she was married, perhaps as a teenager. She announces shes pregnant and we whisper: What happened? Couldnt she keep her legs closed? What went wrong? We think of the darkness. We picture the wet-stained sheets. The tearful acceptance. Her parents. We blame herher cavernous need. Her cavernous stupidity. We blame her, for her failure to live up to an arbitrary moral code. We dont reckon with the societal conditions. What we told (or didnt tell) her about conception. (After all, Texas, with its focus on abstinence-only education, has one of the highest teen pregnancy rates in the nation.) We excuse the boy who refused to wear a condom, but not the girl who didnt push back and insist he wear it. The girl who didnt have access to birth control or who was too ashamed to seek it because of her religion, her family, her lack of money or adequate sex ed or both. No, in those moments we think only of the girl, of her sex.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women»

Look at similar books to Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Belabored: A Vindication of the Rights of Pregnant Women and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.