Copyright 2015 by Spring Publications and Greg Mogenson

All rights reserved

Published by Spring Publications

www.springpublications.com

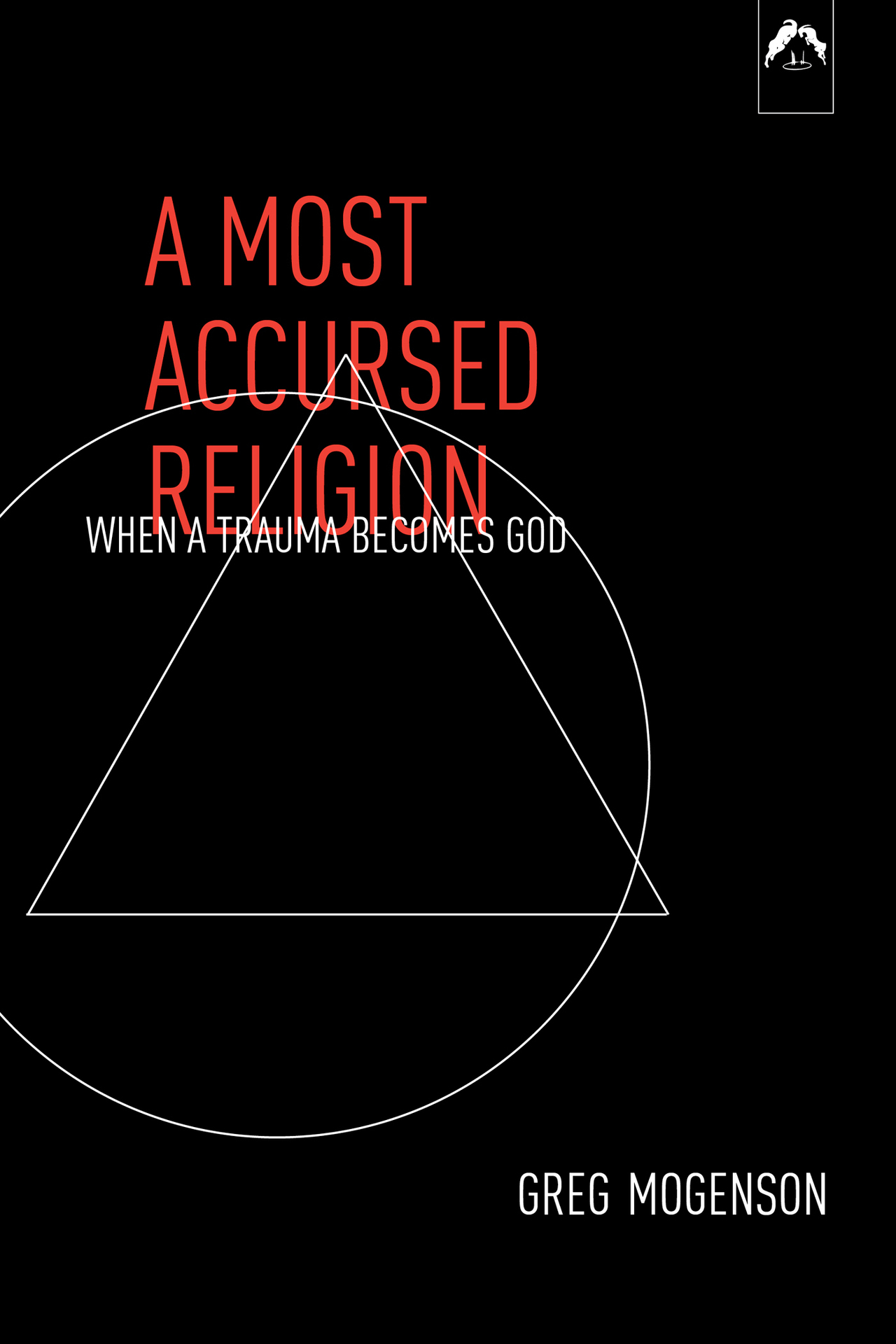

Title Page:

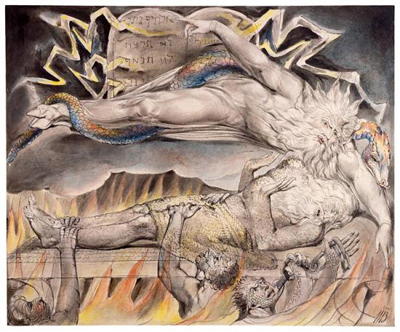

William Blake (17571827)

Job's Evil Dreams

Pen and black ink, gray wash, and watercolor over traces of graphite.

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York

eISBN 978-0-88214-031-5 (revised e-book edition, v. 2.5)

GREG MOGENSON

A MOST

ACCURSED

RELIGION

WHEN A TRAUMA BECOMES GOD

SPRING PUBLICATIONS

THOMPSON, CONN.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to express his gratitude to all those who have supported him in the work that is represented in these pages:

Ross Woodman, Michael Mendis, Rita Mendis-Mogenson, James Hillman, Mary Helen Sullivan, David L. Miller, Peter VanKatwyk, Susan Estabrooks, and Angela Sheppard.

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge permission to reprint as follows:

Section III of Esthtique du Mal, from The Palm at the End of the Mind: Selected Poems and a Play by Wallace Stevens, Vintage Books, originally published by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. by Holly Stevens.

The sections The Infectious Savior, Romanticism, and Into Her Own Hands of this book, previously published in Stepping Out of the Great Code, by Greg Mogenson, in Voices: The Art and Science of Psychotherapy, vol. 21, no. 3/4, Fall 1985/Winter 1986. Voices. Reprinted with permission. The section, Escaping to the Angels, previously published as Escaping to the angels: a note on the passing of the manic defence, by Greg Mogenson, in The Journal of Analytical Psychology 41/1 (January 1996), pp. 7780.

Introduction

This book, despite its title, is not a theology book. It is not a book about God as God. In identifying the words God and trauma in the subtitle, my aim is to focus attention on the religious dimension of the psychology of those overwhelming events we describe as traumatic. When a psychologist writes of God he must do so within the confines of his own field of inquiry, the psyche. Like Jung who, in his own way, tackled themes related to the one facing us here, our references to God in these pages will be to the imago dei, the God-image or God-complex not to God in an ontological sense.

Images and fantasies of God abound in psychic life and have a determining effect upon its movement, regardless of whether a God really exists or not. From the standpoint of theology, a standpoint that attempts to start with God even as psychology starts with psyche, the contention that God is a synonym for trauma will seem grossly reductionistic. After all, to the theologian and the believer, God may be thought of as being in all things even as He is the creator of all things. Again, let me stress: this book is not a theology book. My aim is not to reduce the God(s) of religion and theology to a secularized category of psychopathology, but rather, to raise the secularized term trauma to the immensity of the religious categories which, in the form of images, are among its guiding fictions.

Whether a divine being really exists or not, the psychological fact remains that we tend to experience traumatic events as if they were in some sense divine. Just as God has been described as transcendent and unknowable, a trauma is an event which transcends our capacity to experience or reckon with it. Compared to the finite nature of the traumatized soul, the traumatic event seems infinite, all-powerful, and wholly other. Again, we cannot say that traumatic events literally possess these properties, but only that the traumatized soul propitiates them as if they did.

Human affliction has always been a problem for theology. Indeed, the question How do we reconcile suffering and pain with a loving God? has proven to be among the richest questions sustaining theological reflection. Theologys approach to the problem, of course, has mainly been in the genre of theodicy. Faithful to a benevolent conception of God, theology has attempted to justify the ways of God to age upon age of men and women who have been shattered by events which have lent the created world a malevolent cast. Barth, Tillich, C.S. Lewis, Hans Kng: theologian after theologian has attempted to minister to the interminable struggle of the soul with pain.

Despite the comparisons drawn between the analysts couch and the priests confessional, the difference between the two is perhaps more significant. When he examines the engagement of theology, the psychologist cannot help wondering if theology has placed the needs of the soul secondary to its own need to justify the ways of its root metaphor God. Even those theologians who fastidiously attempt to keep themselves open to the phenomenon of suffering work from an essentially closed perspective in that their thinking is committed from the outset to the service of what they already believe on instinct. For the theologian, the premier psychological question What does the soul want? takes a backseat to the premier theological question What does God demand?

This God first, psyche second priority is not merely academic; it occurs, as well, in the biblical account of mans relationship with God. When we read the Bible, particularly the Old Testament, we meet a God who demands the submissive obedience of the soul to His awesome knowledge and power and who is prepared to test this obedience through torture. Like a cat playing with a mouse, the Creator plays with His creature Job. When Job enquires about Gods motives in torturing him, the divine terrorist answers him out of a storm:

Will you really annul My judgement?

Will you condemn Me

That you may be justified?

Or do you have an arm like God,

And can you thunder with a voice like His?

Adorn yourself with eminence and dignity;

And clothe yourself with honor and majesty.

Pour out the overflowings of your anger

And look on everyone who is proud, and make him low. (Job 40:811)

The controlling metaphor of theology is an overpowering metaphor, a metaphor that literalizes itself in terms of the God-given goodness of affliction and evil. Like Job terrified before the mightiness of God, the theologian, working from a metaphor which denies its relativity as a metaphor, must suppress the objections of his suffering soul. Behold, I am insignificant; what can I reply to Thee? (Job 40:4).

The psychological move from theologys soul-transcending God to the God-complex that stirs within the soul revolutionizes our conception of the traumatized soul. Psychological reflection reverses the God first, psyche second priority. While the theologian writing his theodicy does so with his mouth covered, ever on guard, like Job, lest his representation of suffering seem impious to his Maker, the psychologist tries to amplify the voice of the afflicted psyche. Like Jung in his Answer to Job , he must write without inhibition if he is to give expression to the shattering emotion which the unvarnished spectacle of divine savagery and ruthlessness produces in us.

The theologian, of course, is as skeptical about the humanism of psychology as the psychologist is of the traumatized and traumatizing theism of the theologian. If Man were truly the measure of all things then presumably he would be able to be the measure of his sufferings as well. But the world is bigger than Man. We exist in a creation that transcends us in every direction. If today Mans knowledge and power rival the knowledge and power which Yahweh lorded over Job, will we prove any more judicious than He in our administration of it? The countdown to the Apocalypse has now started, and it is Man the humanist whose finger is on the button, not God.