PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This translation first published 1996

Copyright Alastair Hannay 1996

The moral right of the translator has been asserted

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-141-95866-8

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

PENGUIN CLASSICS

PAPERS AND JOURNALS A SELECTION

Sren Kierkegaard was born in Copenhagen in 1813, the youngest of seven children. His mother, his sisters and two of his brothers all died before he reached his twenty-first birthday. Kierkegaards childhood was an isolated and unhappy one, clouded by the religious fervour of his father. He was educated at the School of Civic Virtue and went on to enter the university, where he read theology but also studied the liberal arts and science. In all, he spent seven years as a student, gaining a reputation both for his academic brilliance and for his extravagant social life. Towards the end of his university career he started to criticize the Christianity upheld by his father and to look for a new set of values. In 1841 he broke off his engagement to Regine Olsen and devoted himself to his writing. During the next ten years he produced a flood of discourses and no fewer than twelve major philosophical essays, many of them written under noms de plume. Notable are Either/Or (1843), Repetition (1843), Fear and Trembling (1843), Philosophical Fragments (1844), The Concept of Anxiety (1844), Stages on Lifes Way (1845), Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846) and The Sickness unto Death (1849). By the end of his life Kierkegaard had become an object of public ridicule and scorn, partly because of a sustained feud that he had provoked in 1846 with the satirical Danish weekly the Corsair, partly because of his repeated attacks on the Danish State Church. Few mourned his death in November 1855, but during the early twentieth century his work enjoyed increasing acclaim and he has done much to inspire both modern Protestant theology and existentialism. Today Kierkegaard is attracting increasing attention from philosophers and writers inside and outside the postmodern tradition.

Alastair Hannay was born to Scottish parents in Plymouth, Devon, in 1932 and educated at the Edinburgh Academy, the University of Edinburgh and University College London, In 1961 he became a resident of Norway, where he is now Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at the University of Oslo. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, he has been a frequent visiting professor at the University of California, at San Diego and at Berkeley. Alastair Hannay has also translated Kierkegaards Fear and Trembling, Either/Or and The Sickness unto Death for Penguin Classics. His other publications include Mental Images A Defence, Kierkegaard (Arguments of the Philosophers), Human Consciousness and Kierkegaard: A Biography, as well as articles on diverse themes in philosophical collections and journals. He is the editor of Inquiry.

In Memory of

PETER FRSTRUP

Journalist, gadfly, friend

Translators Preface

This translation is based on Sren Kierkegaards Papirer (vols. IXI:3, edited by P. A. Heiberg, V. Kuhr and E. Torsting, 190948; supplementary vols. XIIXIII, edited by N. Thulstrup, 196970). The text of Papirer forms the third and most comprehensive edition of Kierkegaards papers and journals, its thirteen titled volumes comprising twenty-five separate bindings (these include three index volumes). A first short-lived attempt to collate the papers was made by his brother-in-law, J. C. Lund, who inherited the entire manuscript collection on Kierkegaards death. Three years later it was handed over to Kierkegaards brother, then Bishop of Aalborg, but nothing more was done with the journal manuscripts until H. P. Barfod undertook the task of compilation in 1865. Unfortunately, Barfod threw away a significant portion of the originals he had transcribed, or at least took no steps to preserve them, so that many of the earlier entries (until 1847) in Papirer have had to be based on Barfods transcriptions. Lunds and Barfods numbering has been preserved. In view of many uncertainties about dates and inaccuracies in transcription, the current Papirer cannot be considered the final version. A definitive text is not only planned, however, but is already being prepared under the auspices of the newly-established Sren Kierkegaard Research Centre at the University of Copenhagen.

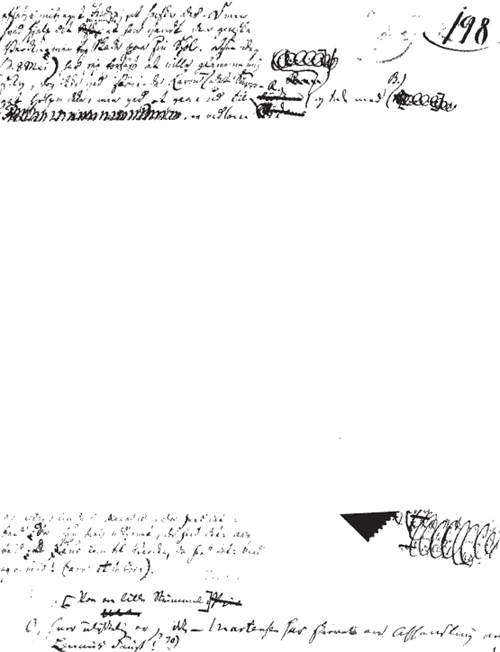

The magnitude of the task may be glimpsed from the sample manuscript page containing entries II A 679 and II A 597. The Papirer transcription of the entry on the right ( II A 68) deviates significantly from the text. But the latter is in Barfods handwriting and is in fact his rough-and-ready transcription of the passage crossed out on the left, while the Papirer transcription is the editors attempt to recover the original more accurately.

We see that Barfod has min Gud (my God) while the editors have read milde Gud (merciful God). They also read Rrdam where Barfod, perhaps from discretion, had put dots though he has replaced them with R.. The editors also take what Barfod transcribes as the second person singular pronoun du in du, min Gud (you, my God) to be capitalized.

The illustration also helps to show the reader what the frequent indication In the margin means. Kierkegaard left plenty of space to make his own changes and insertions, In numbering the entries, the editors have in many cases had to decide for themselves whether an entry was a note to a neighbouring entry or an entry in its own right.

The margin allows us to note a third feature illustrated by the status of entry II A 597 as a loose paper but in Barfods handwriting. Probably the original had been placed with the sheet by Kierkegaard himself, though one cannot be sure. Barfod has transcribed it and the original is lost. The dating of such entries remains uncertain even where the other entries have firm dates, as is by no means often the case.