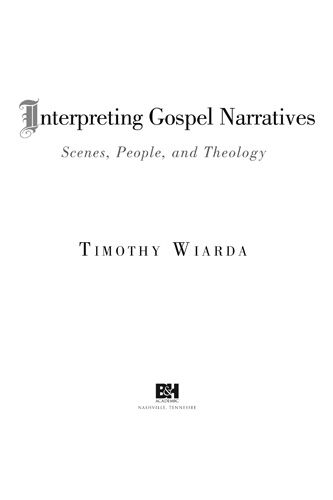

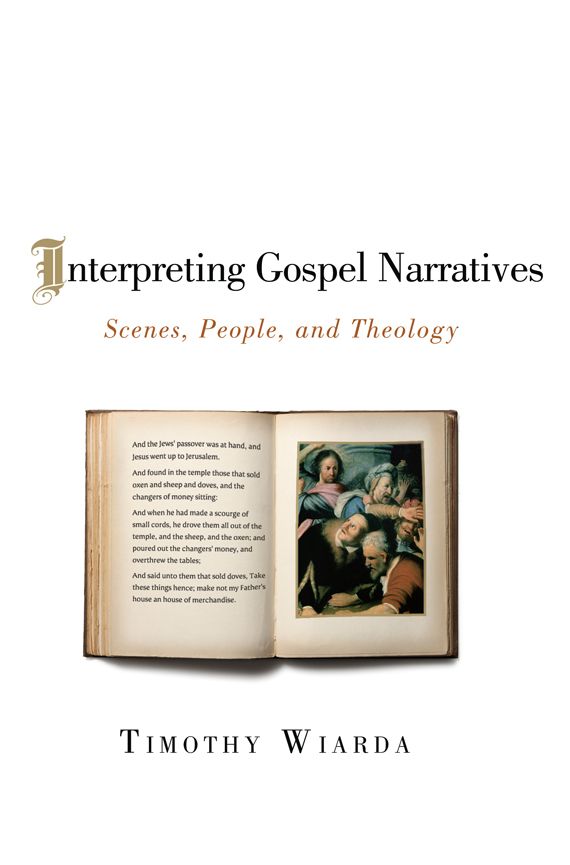

Interpreting Gospel Narratives

Copyright 2010

by Timothy Wiarda

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-8054-4843-6

Published by B&H Publishing Group

Nashville, Tennessee

Dewey Decimal Classification: 226

Subject Heading: BIBLE.N.T.CRITICISM \ JESUS CHRIST

BIBLE.N.T. GOSPELSINSPIRATION

Scripture quotations are translated from the Greek by the author.

Journal, periodical, major reference works, and series abbreviations follow The SBL Handbook of Style (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1999).

Printed in the United States of America

To my students past and present

Contents

Introduction

When the Paraclete comes, whom I will send to you from the Father, the Spirit of truth, who goes out from the Father, he will testify about me. And you also will testify, because you have been with me from the beginning

(John 15:2627).

On the night of his arrest, Jesus spoke to his close followers about two testifying actions, both of which would focus on him. One of them was the testimony of the Paraclete, the Spirit of truth. The other would be their own.

These two testimonies continue to impact the era in which we live. In fact, they are its only source of spiritual life. The testimony of the Holy Spirit is primarily internal: the Spirit opens hearts to the good news about Jesus, sparking faith and transformation. The testifying activity of Jesus first followers, on the other hand, is a matter of outward communication in spoken and written words. These followers, who had been with Jesus from the beginning and were appointed to be apostles, This means they are both eyewitness testimony and divinely authorized testimony.

This book is about interpreting the testimony to Jesus given to us in the Gospels. The goal of such interpretation, as I understand it, is to see the apostles portrait of Jesus as clearly as possible. This portrait is vital because the Holy Spirit bears his life-generating testimony to Jesus today in closest connection with the history-based testimony of those who saw and heard Jesus during his time on earth, both before and after his resurrection.

I am writing especially for those who teach and preach from the Gospels. If the apostles were commissioned to testify to what they had seen and heard during their time with Jesus, we who teach and preach today are given the task of passing their testimony on to others. We must try to pass on a high-resolution picture of Jesus. By high-resolution I do not mean a better picture of Jesus than that given by the authorized eyewitnessesas if with our own inspiration, imagination, intuition, or common sense we might improve on the portraits found in the Gospelsbut rather one that reflects the Jesus of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John as accurately and fully as possible. Imparting such a picture to others requires that we ourselves pursue the enjoyable, challenging, and never quite perfectly achieved task of Gospel exegesis.

In these opening paragraphs I have attempted to provide a quick rationale for what this book is all about: exploring ways that we can enrich our Gospel exegesis. I say more about the importance of Gospel exegesis and exposition in chapter 6. For the moment I need to explain the three things that this book seeks to offer.

First, this is primarily a how-to book. It discusses questions of exegetical method with the aim of helping interpreters and expositors work with Gospel texts. Along the way it also offers brief expositions of a number of Gospel episodes. While I hope readers will find these expositions helpful for the light they throw on various Gospel episodes, the chief purpose of each study is to illustrate a particular methodological issue.

Second, this book discusses methodological questions relating specifically to the Gospels narrative material. Some of these relate to our appreciation of the entire integrated story each Gospel presents, but most concern our handling of the smaller units of narrative embedded in these large wholes.

Third, this book has a special focus. Rather than providing a broad general survey of the entire task of narrative interpretation, it zeroes in on four specific issues. (1) We will ask questions about the way Gospel narratives portray individual characters. To what extent do Gospel writers display an interest in characters other than Jesus? What literary forms does this interest take? What do Gospel narratives signal about the feelings, attitudes, motives, responses, and struggles of the individual figures that appear in them? (2) We will examine how descriptive detailsthe actions, objects, times, and places the Gospels set before our eyesfunction in concrete scenes and unfolding plots. (3) We will consider the relation between theology and story in Gospel narratives. I attempt to show that, when the evangelists communicate pastoral points, they do so in and through the concrete stories they tellstories that are shaped with scenic detail, nuanced characterization, and attention to individual experience. (4) Finally, we will explore questions arising from the episodic nature of the Gospel narratives. How do individual narrative units function in whole Gospels? How can interpreters attend to what an individual episode says on its own terms while at the same time giving due weight to features that mark the whole Gospel in which it appears as a single unified narrative?

This book does not offer a comprehensive survey of narrative critical methods,books about the Gospels, books about hermeneutics and exegesis, books about narrative criticismbut such works are often obliged to treat significant questions in cursory fashion. Important distinctions may be blurred in the process and there may be little space for examining actual texts. The present study, by way of contrast, focuses on a limited cluster of interrelated topics and can thus examine and illustrate issues in greater detail.

The topics this study takes up are important because they deal with aspects of interpretation that bear particularly rich exegetical fruit. Sensitive attention to the portrayal of individual characters enhances and sharpens Gospel exegesis. So does heightened awareness of descriptive details and sensitivity to their function in narrative scenes. But these matters have often suffered a measure of neglect. Traditional Gospel scholarship has frequently hesitated to give too much attention to individualizing characterization, and it has not been consistently adept at handling descriptive details. The newer literary critical approaches to the Gospels, marked as they are by greater sensitivity to plotting and characterization, have opened new doors in these areas. And yet there is much room for further exploration. The insights provided by narrative criticism are not always applied as fully as they might be, particularly when it comes to brief scenes, small details, and individual characters.

The connection between story and theology has received somewhat more attention among Gospel scholars, as has the relation of episodes to whole Gospels. But scholars have taken quite diverse positions on these issues. With respect to the story-theology relationship, at one end of the spectrum are those who view Gospel stories as mere vehicles for theological propositions and, at the other, those who claim that Gospel narratives operate on a plane totally removed from the communication of specific concepts. As for the relation between episodes and whole Gospels, some scholars insist that each Gospel constitutes a tightly integrated narrative unity, while others see the Gospels as more loosely connected collections of self-standing episodes. There is thus a need for greater clarity about these matters. And we should not think these issues are the concern of academic specialists alone. All who read and teach the Gospels have to adopt some position with respect to these questions, even if they do so unwittingly. The positions they take impact the way they approach and interpret Gospel texts.

Next page