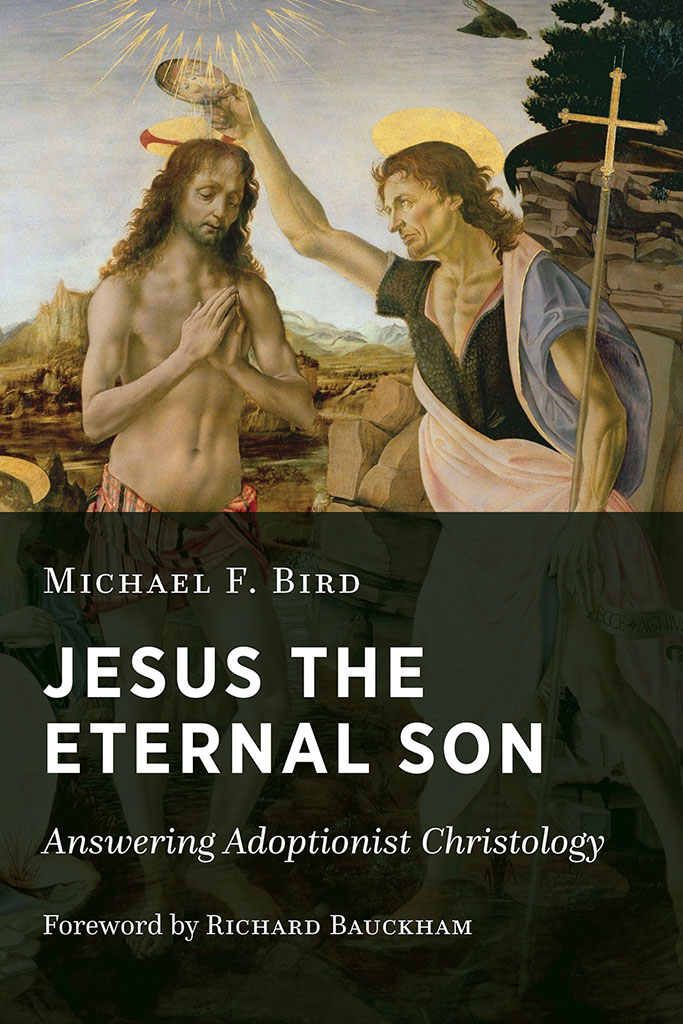

Jesus the Eternal Son

Answering Adoptionist Christology

Michael F. Bird

WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY

GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505

www.eerdmans.com

2017 Michael F. Bird

All rights reserved

Published 2017

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 171 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

ISBN 978-0-8028-7506-8

eISBN 978-1-4674-4789-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bird, Michael F., author.

Title: Jesus the eternal son : answering adoptionist Christology / Michael F. Bird.

Description: Grand Rapids : Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017010013 | ISBN 9780802875068 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Jesus ChristPerson and offices. | Jesus ChristDivinity. | Adoptionism.

Classification: LCC BT203 .B536 2017 | DDC 232/.8dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017010013

For the three Craigs

Craig Evans

Craig Keener

Craig Blomberg

Table of Contents

For some time now, early Christology has been the subject of intense and lively debate. The result has been important and fresh research. What did the earliest Christians really think about Jesus? is a question on the minds of many people. Did early believers in Christ really worship him as a divine figure? Or did they think of Jesus as a merely human figure whom God had exalted to a position of great eminence? Was the earliest Christology to which we have access already very high, as the scholarly trend known as early high Christology has argued? A wide range of scholars now think so; Michael Bird is prominent among them. However, many scholars still defend an older model of the evolution of Christology from what has often been called an adoptionist view toward an understanding of Jesus as the divine Son of God incarnate, which was perhaps only reached toward the end of the New Testament period, in the Gospel of John. There have been important recent challenges to early high Christology, some of which offer relatively new suggestions about the ideas available in the context of early Christianity that could have provided a model for Christian interpretation of Jesus. Birds book engages with some of those ideas, especially with the ones about the deification of Roman emperors and other prominent human beings. Such proposals build on a long scholarly tradition of reading certain key New Testament texts as evidence for an early view of Jesus as a man whom God adopted as his son, whether at his resurrection or at his baptism.

This book is very welcome because, surprisingly, the idea of divine sonship has not received the attention it deserves in the discussion of early high Christology. Yet it has a central role in the New Testament as a whole. It embodies the sense that Jesus did not come to be divine but came from God in the first place. It is the key notion that ties together his pre-existence, his earthly life, and his exaltation in continuity. It is the way that early Christians came to be able to think of Jesuss relationship to God his Father as an inner divine reality. It functions both exclusively (designating Jesuss unique relation to his Father) and also inclusively, as the relationship to God that Jesus enables believers to share. As such, it belongs to both a Christological and a soteriological category.

So did it all start with the view that divine sonship was a status that the man Jesus gained by merit and divine appointment? Birdalthough he allows for variation and gradually clearer definition in early Christologyfinds that there is no evidence at all for adoptionism in the early period. He tackles the texts that have so often been read in an adoptionist way and shows, I think convincingly, that this cannot plausibly be the original meaning. In his search for the origins of adoptionism, Bird moves into the second century and finds what he is looking for only at the very end of that century. Far from being considered the earliest Christology, adoptionism now appears to be actually a very late divergence from the main current of Christian thinking on the subject. Instead of being a view that preceded any ontological thinking about Jesuss relation to God, it turns out to be a view designed to protect an ontology of divine nature that could not accommodate incarnation within it. Many New Testament scholars will likely be surprised by this conclusion, but many patristic scholars, I suspect, will not.

I am happy to commend this learned, cogent, and significant book.

RICHARD BAUCKHAM

This volume is the result of preparation for a public dialogue about the divinity of Jesus held at the Greer-Heard Point-Counter-Point forum at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary in February 2016. Participants included Bart Ehrman, Jennifer Knust, Dale Martin, Larry Hurtado, Simon Gathercole, and me.

As I began preparing my talk on Jesus and adoptionism, it soon became apparent to me that a lot of what was being said about the origins of christological adoptionism was incorrect. What is more, in response to all this, it soon became clear that I had more to communicate than I had time to speak. What I wrote for the Greer-Heard debate was too substantial for a lecture or even for a journal article on the subject and more suited in length for a short, sharp, and provocative volume on the topic. So here we are!

I first gained interest in the topic of adoptionism after noticing that many scholars simply assume rather than argue the point that the earliest Christology of the primitive church was adoptionistic. The only evidence mustered is more often than not a footnote to the same cohort of scholars, usually John Knox and James D. G. Dunn, but without ever critically appraising their theses. My own suspicion was that, to quote George Gershwin, it aint necessarily so. I would not for a moment deny the diversity of portraits of Jesus that emerged in the early church, some emphasizing his humanity. However, in my reading of the sources a mature adoptionism is a second-century phenomenon. The first real and tangible advocates were the Theodotians.

I would like to thank Bob Stewart for inviting me again to the Greer-Heard forum. I would also like to thank my fellow participants in the discussion and those who made the event possible. The Nawleans hospitality and collegiality was outstanding! I love being able to say that I have had blackened crawfish from down on the bayou!

Several friends read over parts of the manuscript and offered comments for which I am most grateful. Joshua Jipp, once the apprentice now the master, was great with corrections, affirmations, and suggestions. So too did Matthew Bates have a close read of the manuscript and point out to me certain ways to enhance it. Con Campbell answered a hairy Greek question for me. My colleague Scott Harrower made a few learned comments too. Christoph Heilig helped track down a few German works that were inaccessible to me. Michael Peppard provided some crucial feedback in making sure I represented his view correctly. He also pushed back on several vital details. An anonymous reviewer supplied by Eerdmans made several pointed suggestions as to how to improve the quality of the argumentation and readability of the book, for which I am most grateful. Also, the Ridley librarians Ruth Millard and Alison Foster ordered several volumes that I needed to read in order to complete the book. Thanks also go to John Schoer for ably compiling the indexes.

This volume is dedicated to three guys called Craig, scholars whose work on Jesus and the Gospels has taught me much and inspired me to excellence in my own writing. First, I read Craig Blombergs textbooks on