Contents

Guide

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2020 by Wendy Williams

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition May 2020

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Ruth Lee-Mui

Jacket design by Math Monahan

Jacket photograph by Kelvin Hudson / Millennium Images, UK

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Williams, Wendy, 1950 author.

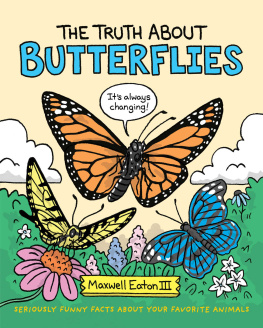

Title: The language of butterflies : how thieves, hoarders, scientists, and

other obsessives unlocked the secrets of the planets favorite insect /

Wendy Williams.

Description: New York : Simon & Schuster, 2020. | Includes bibliographical

references and index. | Summary: In this fascinating book from the New

York Times bestselling author of The Horse, Wendy Williams explores the

lives of one of the worlds most resiliant creaturesthe

butterflyshedding light on the role that they play in our ecosystem

and in our human livesProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019025246 (print) | LCCN 2019025247 (ebook) | ISBN

9781501178061 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781501178078 (paperback) | ISBN

9781501178085 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Butterflies]Popular works.

Classification: LCC QL544 .W55 2020 (print) | LCC QL544 (ebook) | DDC

595.78/9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019025246

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019025247

ISBN 978-1-5011-7806-1

ISBN 978-1-5011-7808-5 (ebook)

For

LINCOLN BROWER

(19312018)

and to the memory of murdered activist

HOMERO GMEZ GONZLEZ

(19702020)

Nature has a perverse preference for the six-legged.

Michael S. Engel

Introduction

Color is a power which directly influences the soul.

Wassily Kandinsky

L ong ago, when I was twenty, penniless, and hanging in London, looking for something free to do, I drifted into the citys Tate Galleryfilled with some of the worlds best-known artand walked straight into a staggering J. M. W. Turner masterpiece.

I was gobsmacked.

Knocked for a loop.

Brilliant and shimmering, shrieking with yellows and oranges and reds swirling around smoky-vague outlines of battling ships at sea, that painting owned me.

If youve seen Turners creations, you know why. His works tap into a secret crevasse in the human psyche, a down-the-rabbit-hole neural pathway from which, for some of us, there is no escape. Its a biological thing. An evolutionary mandate. Only recently discovered by science but long understood intuitively by artists, this hidden desire elicits a unique kind of hypnotic trancea craving for color.

Standing before Turners work, I was mesmerized.

I tried to wind my way through the mysteries of the thing. This was pure experience. I knew nothing about Art. I was an innocent. I had no idea who Turner was, no clue that he was considered a genius who paved the way for Impressionism. I had not been prepped to venerate his work. This was a once-in-a-lifetime thing.

A first kiss.

I was never again so deliciously, so exquisitely, so naively shocked.

Until

I was sucker-punched once again. This time it was in Larry Galls Yale University offices. Interested in the crazy, titillating, and sometimes even deadly world of butterfly obsession, I had come to meet Gall, the universitys trim, bespectacled computer expert and keeper of more than a centurys worth of butterfly, moth, and caterpillar collections. Brought to Yale from locations worldwide were thousands upon thousands of boxes of carefully pinned and lovingly recorded specimens of Lepidopterabutterflies and moths.

Like the Turner, these boxes were monumental works of art. But unlike the massive Turner seascapes Id loved, these boxes had been squirreled away for decades in hundreds upon hundreds of protective climate-controlled drawers. Assembled by compulsive butterfly addicts who worked in isolation in rooms and jungles and labs worldwide, some boxes dated to the eighteenth century.

The artists who made them obviously combined a deep passion for color with a meticulousness for detail. These kaleidoscopic assemblages represented hundreds of lifetimes of devoted labor by men and women hunched over their desks, working with a steadiness of hand and of intention that I could only dream of.

More than four decades after my life-changing love-at-first-sight view of a Turner, I was stunned all over again. I wanted to see more.

And more.

There was a lot to see. Yale has literally hundreds of thousands of butterfly and moth specimens. The boxes are cosseted in drawers that run from floor to ceiling, in line upon line of cabinets, in the expectation that someday, somewhere in the universe, whether in our own Milky Way or beyond, some researcher, perhaps yet unborn, will need them for a study.

Neatly pinned in meticulous rows, entire trays were devoted to only one species. The best of these boxes also note when and where the samples were collected.

Gall patiently pulled tray after tray after tray of butterflies. Just as with Turners painting, I struggled to make sense of what I saw. Who knew that trays of dead insects could be so delicious, so sensuous, so entirely luscious?

Eventually Gall, himself an addict, wearied of me and my incessant Why this? and Why that? I was politely, gently, but definitively dismissed.

And so I learned that the butterfly effect (to repurpose a term) is real, that this craving for color so deeply hardwired in our brains could turn into an addiction. What had been an arms-length inquiry into the unusual desires of certain lepidopterists had exploded into a compulsion of my own: What exactly were these odd flying creatures, some so small as to be almost invisible but others with foot-wide wingspans?

Like most people, I was no stranger to butterflies. Butterflies had been my companions for most of my life, as I rode horses through high Rocky Mountain valleys or over rich wildflower-filled Vermont fields. They were common in the Pennsylvania meadows where I grew up, as they were when I lived in Senegal or traveled in Zimbabwe or Kenya or South Africa. Everywhere I walked among weeds and wildflowers, butterflies fluttered. As I hiked Appalachias mountain trails, or strolled the beaches of Cape Cod, butterflies were there.

Of course I had seen them. Of course I liked them. Who doesnt? But I took them for granted. I hadnt really looked at them. Not closely, that is. Where did they come from? Why were they here? What the heck do they get up to while theyre on our planet? And what is it about them that compels the human psyche so insistently that men and women have risked their fortunes and their lives and, on occasion, died in order to capture them?