JAMES A. HAUGHT

the more than one thousand quotations in this volume have been gathered over three decades from scores of books and other sources. Where possible, I cite original sources. Many quotes, however, were drawn from existing anthologies and collections, and their help is gratefully acknowledged.

the more than one thousand quotations in this volume have been gathered over three decades from scores of books and other sources. Where possible, I cite original sources. Many quotes, however, were drawn from existing anthologies and collections, and their help is gratefully acknowledged.

Edward M. and Michael E. Buckner, Quotations That Support the Separation of Church and State (The Atlanta Freethought Society, 1993).

Charles Q. Bufe, ed., The Heretic's Handbook of Quotations: Cutting Comments on Burning Issues (Tucson, Ariz.: See Sharp Press, 1992).

Ira D. Cardiff, What Great Men Think of Religion (Christopher Publishing House, 1945; reprint New York: Arno Press, 1972).

Carole Gray, designer of the 1992 Atheist Desk Calendar and the 1993 and 1994 Women of Freethought Calendars, Columbus, Ohio.

Rev. Roger E. Greeley, ed., The Best of Humanism (Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1988).

H. L. Mencken, A New Dictionary of Quotations (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966).

Rufus K. Noyes, Views of Religion (Boston: L. K. Washburn, 1906).

Laurence J. Peter, Peter's Quotations: Ideas for Our Time (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1977).

George Seldes, ed., The Great Quotations (New York: Lyle Stuart, 1960).

Thomas S. Vernon, Great Infidels (Fayetteville, Ark.: M&M Press, 1989).

Laird Wilcox and John George, eds., Be Reasonable: Selected Quotations for Inquiring Minds (Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1994).

In this book, quotations from these collections are marked (Cardiff), (Seldes), (Vernon), and so on.

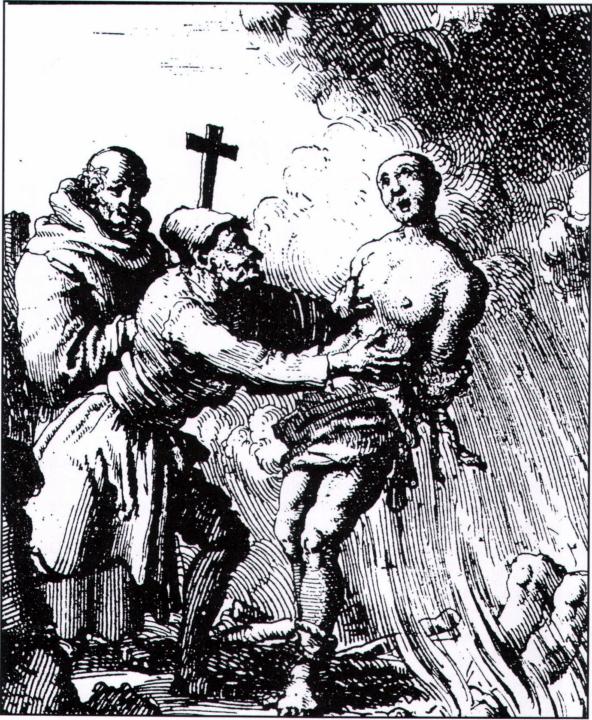

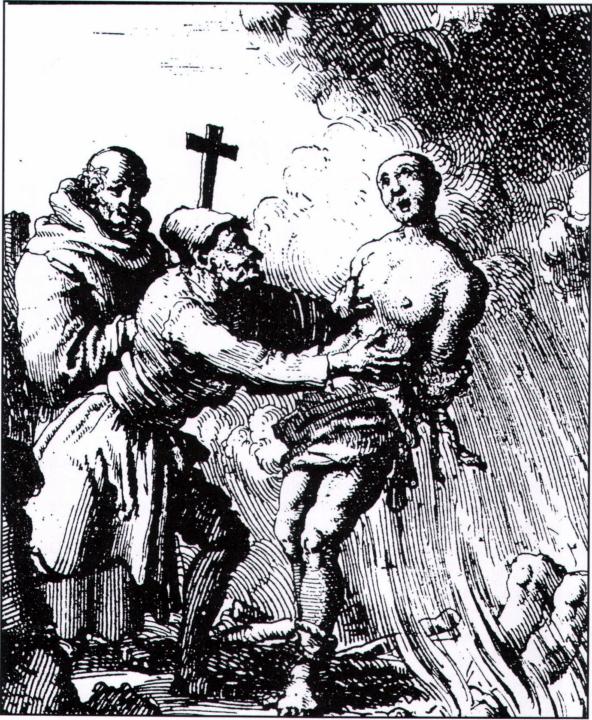

For more than two thousand years, at different times and places, from ancient Greece to strict Muslim lands today, doubters of prevailing religious dogmas have risked jailing, flogging, banishment-or worse. (Engraving by Jan Luyken from Martyrs Mirror, The Netherlands, 1685)

ntelligent, educated people tend to doubt the supernatural. So it is hardly surprising to find a high ratio of religious skeptics among major thinkers, scientists, writers, reformers, scholars, champions of democracy, and other world changerspeople usually called great.

ntelligent, educated people tend to doubt the supernatural. So it is hardly surprising to find a high ratio of religious skeptics among major thinkers, scientists, writers, reformers, scholars, champions of democracy, and other world changerspeople usually called great.

The advance of Western civilization has been partly a story of gradual victory over oppressive religion. The rise of humanism slowly shifted society's focus away from obedience to bishops and kings, onto individual rights and improved living conditions. Much of the progress was impelled by men and women who didn't pray, didn't kneel at altars, didn't make pilgrimages, didn't recite creeds.

Since disbelief remains a taboo topic, this pattern is rarely mentioned. Churchmen generally contend that great figures in history, such as America's founders, were conventional worshipers. That's untrue.

Most of the founders were Deists, roughly equivalent to Unitarians, who doubted that Christ was a god, yet praised his message of compassion. They spoke of God as the power behind nature, as discerned by science.

Other pioneers in many fields in many centuries included nonconformists of all sorts, from mild dissidents to outright atheists.

Western culture has traveled an erratic journey. Ancient Greece and Rome teemed with intellectual inquiry, amid polytheism. Then the Christian Age of Faith brought darkness for centuries. The Renaissance revived individualism and free thinking, which soared in the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment. With the flowering of science in the nineteenth century, many thinkers assumed that mystical religion would vanish. Among intellectuals, it largely has done so. But dogma and fundamentalism have resurfaced in society at large.

Disbelief always has remained partly hidden, because it entails risk. Believers can inflict terrible punishments on doubters. During eras when religion was supreme, nonconformists lived in peril. Here are some examples:

In 399 B.C.E., Socrates was condemned by a 500-man Athenian jury on vague charges, including an accusation that he was guilty of "not worshiping the gods whom the state worships." His predecessor, Anaxagoras, likewise was sentenced to death for teaching that the sun and moon are natural objects, not deities, but he fled into exile. Protagoras was banished from Athens for saying he didn't know if the gods exist. His books were burned, and he perished at sea.

In the year 385, the Spanish ascetic Priscillian was executed for holding an unorthodox view of the Trinity and other variant beliefs.

In 415, the great woman scientist Hypatia, head of the renowned Alexandrian Library, was beaten to death by Christian monks who considered her a pagan.

Around 550 at Constantinople, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian executed multitudes to impose Christian orthodoxy.

After the Reformation, both Catholic and Protestant authorities killed "blasphemers" such as the physician Michael Servetus, who discovered the pulmonary circulation of blood. He was burned alive in John Calvin's Geneva in 1553 for doubting the Trinity.

Matthew Hamount went to the stake in 1579 at Norwich, England, after priests accused him of saying that the Bible "is but foolishness, a mere fable; that Christ is not God or the savior of the world, but a mere man...."

The Roman Inquisition burned philosopher Giordano Bruno in 1600 for contending that the earth circles the sun, and that the universe is infinite. A generation later, the Inquisition sentenced Galileo to life confinement for writing his belief that the earth moves.

In 1697, a young man was burned at Edinburgh for ridiculing the Bible.

In 1766, a French teenager, Chevalier de La Bane, was beheaded on charges that he had marred a crucifix, sung irreligious songs, and worn his hat while a religious procession passed.

For every nonconformist executed, hundreds were jailed, tortured, fined, flogged, censured, banished, or ostracized. Understandably, few people dared voice skepticism. However, by the eighteenth century, with a slight loosening of the church's grip, a few bold French and English rebels-especially thinkers allied with Voltaire-ventured into dangerous water. They promulgated Deism and Unitarianism, denying the divinity of Jesus and rejecting miracles, while contending that God can be seen in patterns of nature and the universe. A brazen few expressed outright atheism.

the more than one thousand quotations in this volume have been gathered over three decades from scores of books and other sources. Where possible, I cite original sources. Many quotes, however, were drawn from existing anthologies and collections, and their help is gratefully acknowledged.

the more than one thousand quotations in this volume have been gathered over three decades from scores of books and other sources. Where possible, I cite original sources. Many quotes, however, were drawn from existing anthologies and collections, and their help is gratefully acknowledged.

ntelligent, educated people tend to doubt the supernatural. So it is hardly surprising to find a high ratio of religious skeptics among major thinkers, scientists, writers, reformers, scholars, champions of democracy, and other world changerspeople usually called great.

ntelligent, educated people tend to doubt the supernatural. So it is hardly surprising to find a high ratio of religious skeptics among major thinkers, scientists, writers, reformers, scholars, champions of democracy, and other world changerspeople usually called great.