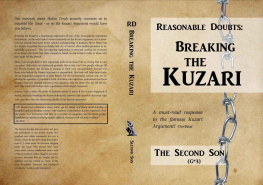

This book owes a lot to the bloggers of the old Jewish skeptic blogosphere with whom I had many stimulating conversations over the years, and to members of Facebook groups with whom I had similar conversations. Much of the material in the following pages was gleaned from or inspired by the many people who have taken the time to write about, argue about, and discuss the Kuzari Argument in various online forums.

I'd also like to thank Phil Rubyn (whatever your real name is) for generously giving his time to edit sections of this book and for teaching me how to polish my writing.

I will set down a tale as it was told to me by one who had it of his father, which latter had it of his father, this last having in like manner had it of his father- and so on, back and still back, three hundred years and more, the fathers transmitting it to the sons and so preserving it. It may be history, it may be only legend, a tradition. It may have happened, it may not have happened: but it could have happened. It may be that the wise and the learned believed it in the old days; it may be that only the unlearned and the simple loved it and credited it.

CHAPTER 1:

Introduction

I have observed that the world has suffered far less from ignorance than from pretensions to knowledge. It is not skeptics or explorers but fanatics and ideologues who menace decency and progress. No agnostic ever burned anyone at the stake or tortured a pagan, a heretic, or an unbeliever.

Daniel Boorstin, The Amateur Spirit, from Living Philosophers

The Kuzari Argument is, at its simplest, the contention that the tradition of the giving of the Torah to the entire Jewish nation at Sinai by God is in itself evidence or proof that the Torah was given to the entire Jewish nation at Sinai by God. It has its origins in medieval Jewish thinkers such as Saadya Gaon, R' Yehuda HaLevi, and the Ramban. It is, as far as I know, the only theological argument that is uniquely Jewish. It's not borrowed from or based on Greek philosophy or Christian or Muslim theology, as are other widely used arguments for the truth of Judaism.

Despite its age, the Kuzari Argument doesn't seem to have been a prominent argument for Judaism until fairly recently. It gained prominence in the modern era as a response to rationalist critiques of Judaism. As an argument unique to Judaism, it's used to provide a rational basis for belief in Judaism that doesn't also endorse other faiths. It's now one of the arguments used regularly by those doing kiruv , and most frum people are aware of it in its informal forms. For many, it forms the linchpin of the theological construct that underlies their belief in Judaism as the one true religion. Only Judaism, they argue, had a mass revelation by God to the entire nation; other religions are based on the testimony of a single person, who for all we know may have been a charlatan or a lunatic.

The popularity and prominence of the Kuzari Argument is what warrants the in-depth attention I'm giving it. This book began as a chapter in a much larger work where I show that rejecting the position that Judaism is the truth is a conclusion that sane, intelligent people can reasonably come to - and that rejecting Judaism's truth-claims is at least as reasonable as accepting them. As I gathered sources and materials for the chapter on the Kuzari, my notes grew longer and longer, until it reached the point where it seemed best to discuss it in its own separate book.

The Kuzari as a Support Vs. as a Bludgeon

The Kuzari Argument, along with the Argument from Design, " "[people] don't worship idols except to permit to themselves sexual licentiousness."

Many frum people believe that Judaism is obviously correct. After all, the midrash

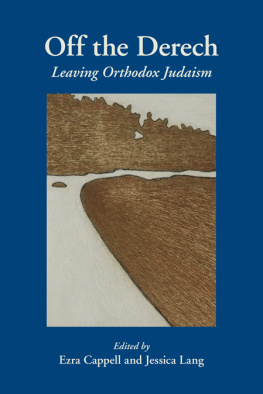

The taivos canard has been softened recently. Now people who go OTD are assumed to be broken rather than wicked. They are thought to have mental disorders, to come from difficult family situations, to have been abused, or to have suffered some other trauma. This is, marginally, better than accusing them of being weak-willed hedonists looking for excuses to reject Judaism in order to assuage their guilt over their sinful excesses. But it's still insulting to those who leave frumkeit , many of whom, like myself, have spent years thinking and learning about theology and Judaism and have concluded that the arguments in Orthodox Judaism's favor are not convincing.

Perceiving people who go OTD as broken allows believers to remain secure in the conviction that their faith is unquestionably the truth, and to be dismissive toward those who question it. Worse, many people who question the truths with which they were raised internalize the frum attitude toward the questioner. The questioner is a fool, a rasha , a broken person who cannot or will not see the truth that's obvious to everyone around them.

It's in order to combat this harmful attitude that I'm writing this book. I have no particular desire to undermine anyone's emunah . I have no argument with frum people who use the Kuzari Argument to support their belief in Judaism, but still recognize that other people can reasonably come to different conclusions. This book is not addressed to those people. It's for those who assume that their position is obviously the only correct one, and that anyone who disagrees must have something wrong with them. It's for the people who are questioning frumkeit , and think that they must be the crazy ones if everyone around them disagrees. It's to show that the Kuzari Argument is not the firm foundation for frumkeit that many people think it is, and that its failure leaves that much more of Yiddishkeit to rest on a fragile foundation of faith.

The Argument in Classical Sources

The Kuzari Argument gets its name from the Sefer Kuzari , written by R' Yehuda HaLevi in the eleventh century. R' Yehuda relates the probably apocryphal story of the king of the Khazar's conversion to Judaism. The king summoned a representative of each of the Abrahamic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and asked each to present arguments for why he should adopt their religion.

The rabbi representing Judaism tells the king that despite their trust in Moshe Rabeinu and even after seeing the miracles of yetzias Mitzrayim , the Jewish people still doubted that God, a transcendent Being, spoke to people. To allay their doubts, God brought them to Har Sinai and with great spectacle gave Moshe the Aseres HaDibros . The whole nation witnessed God give the Ten Commandments and heard Him speak. After this demonstration, the people had no more doubts about whether God spoke to Moshe.

The Khazar king replies that anyone hearing the rabbi claim that God had spoken to the people and given them laws would accuse the rabbi of anthropomorphizing God. The rabbi, though, is justified in his claim because of the thousands of people who witnessed Matan Torah . He knows Judaism is true not through mere reason, but because the testimony of so many witnesses is undeniable.

Although named for the Sefer Kuzari , the core of what's now called the Kuzari Argument first appeared a century earlier in Saadya Gaon's work Emunos v'Deos . Saadya Gaon argues that people could never come to believe a tradition of a miracle observed by the whole nation unless it had really happened. The ancestors of the Jewish people would never have agreed to spread a story they believed to be a lie, and even if they had, their children would never have believed it.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents