Table of Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

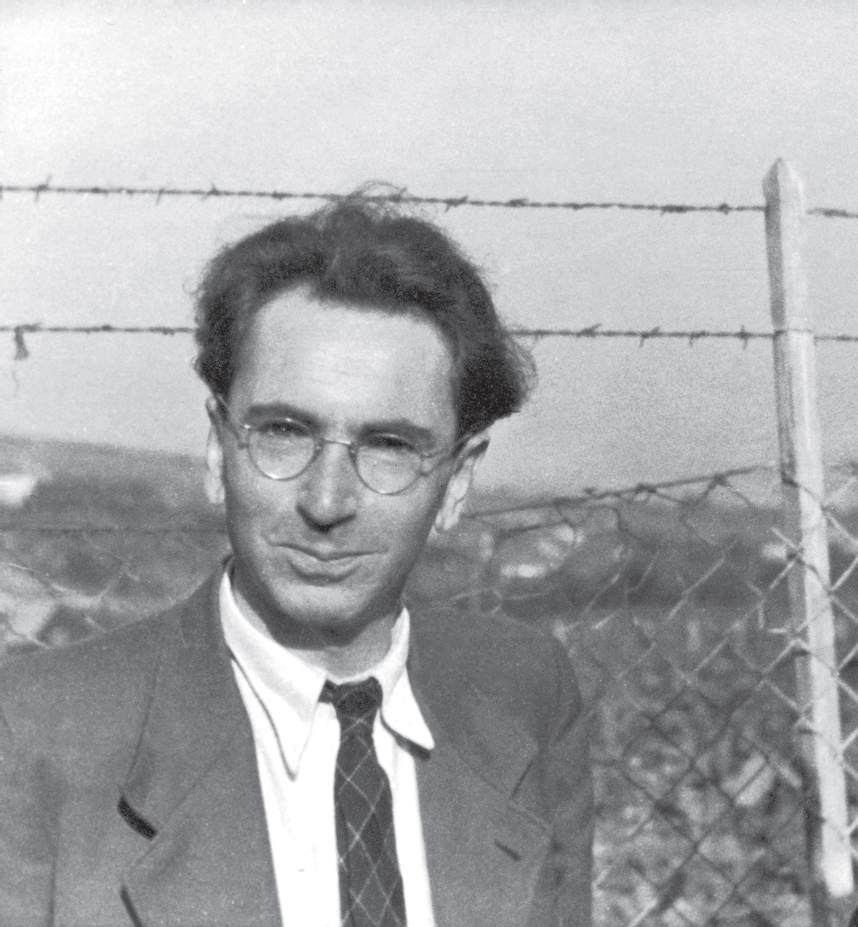

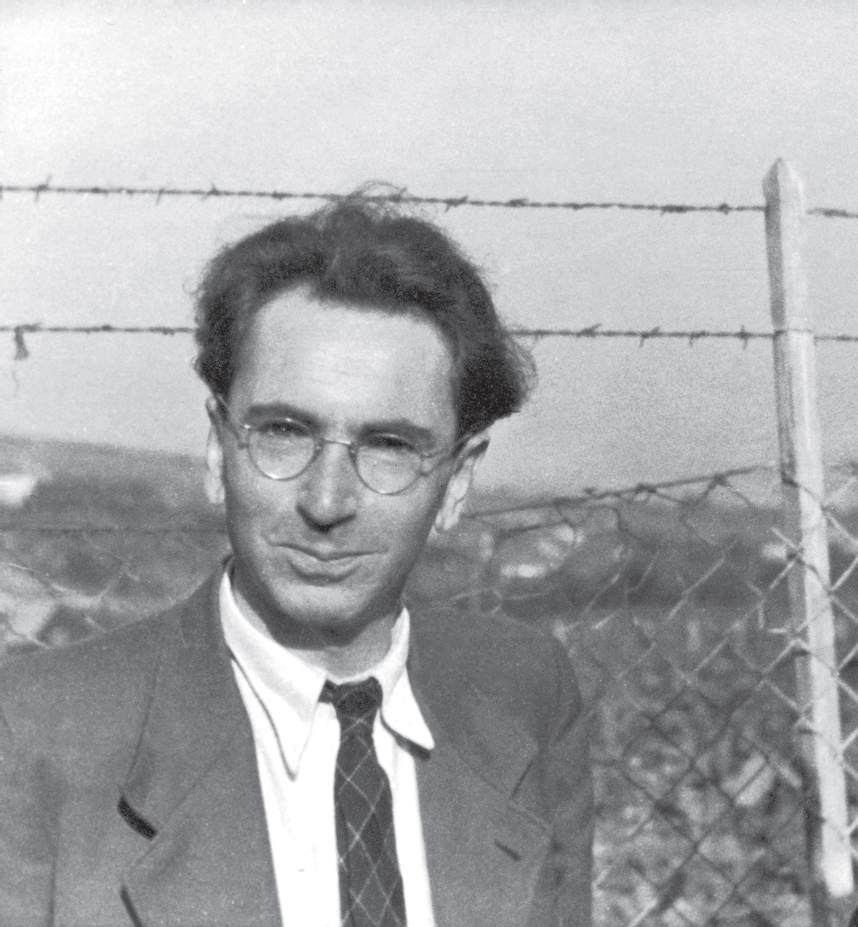

Viktor E. Frankl, 1946

To my late father

INTRODUCTION

Saying Yes to Life

I T S A MINOR MIRACLE THIS BOOK EXISTS . THE LECTURES that form the basis of it were given in 1946 by the psychiatrist Viktor Frankl a scant eleven months after he was liberated from a labor camp where, a short time before, he had been on the brink of death. The lectures, edited into a book by Frankl, were first published in German in 1946 by the Vienna publisher Franz Deuticke. The volume went out of print and was largely forgotten until another publisher, Beltz, recovered the book and proposed to republish it. Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything has never before been published in English.

During the long years of Nazi occupation, Viktor Frankls audience for the lectures published in this book had been starved for the moral and intellectual stimulation he offered them and were in dire need of new ethical coordinates. The Holocaust, which saw millions die in concentration camps, included as victims Frankls parents and his pregnant wife. Yet despite these personal tragedies and the inevitable deep sadness these losses brought Frankl, he was able to put such suffering in a perspective that has inspired millions of readers of his best-known book, Mans Search for Meaningand in these lectures.

He was not alone in the devastating losses and his own near death but also in finding grounds for a hopeful outlook despite it all. The daughter of Holocaust survivors tells me that her parents had a network of friends who, like them, had survived some of the same horrific death camps as Frankl. I had expected her to say that they had a pessimistic, if not entirely depressed, outlook on life.

But, she told me, when she was growing up outside Boston her parents would gather with friends who were also survivors of the death campsand have a party. The women, as my Russian-born grandmother used to say, would get gussied up, wearing their finest clothes, decking themselves out as though for a fancy ball. They would gather for lavish feasts, dancing and being merry togetherenjoying the good life every chance they had, as their daughter put it. She remembers her father saying Thats living at even the slightest pleasures.

As she says, They never forgot that life was a gift that the Nazi machine did not succeed in taking away from them. They were determined, after all the hells they had endured, to say Yes! to life, in spite of everything.

The phrase yes to life, Viktor Frankl recounts, was from the lyrics of a song sometimes sung sotto voce (so as not to anger guards) by inmates of some of the four camps in which he was a prisoner, the notorious Buchenwald among them. The song had bizarre origins. One of the first commanders of Buchenwaldbuilt in 1937 originally to hold political prisonersordered that a camp song be written. Prisoners, often already exhausted from a day of hard labor and little food, were forced to sing the song over and over. One camp survivor said of the singing, we put all our hatred into the effort.

But for others some of the lyrics expressed hope, particularly this:

... Whatever our future may hold:

We still want to say yes to life,

Because one day the time will come

Then we will be free!

If the prisoners of Buchenwald, tortured and worked and starved nearly to death, could find some hope in those lyrics despite their unending suffering, Frankl asks us, shouldnt we, living far more comfortably, be able to say Yes to life in spite of everything life brings us?

That life-affirming credo has also become the title of this book, a message Frankl amplified in these talks. The basic themes that he rounded out in his widely read book Mans Search for Meaning are hinted at in these lectures given in March and April of 1946, between the time Frankl wrote Mans Search and its publication.

For me there is a more personal resonance to the theme of Yes to Life. My parents parents came to America around 1900, fleeing early previews of the intense hatred and brutality that Frankl and other Holocaust survivors endured. Frankl began giving these talks in March of 1946, just around the time I was born, my very existence an expression of my parents defiance of the bleakness they had just witnessed, a life-affirming response to those same horrors.

In the rearview mirror offered by more than seven decades, the reality Frankl spoke to in these talks has long gone, with successive generational traumas and hopes following one on another. We postwar kids were by and large aware of the horrors of the death camps, while today relatively few young people know the Holocaust occurred.

Even so, Frankls words, shaped by the trials he had just endured, have a surprising timeliness today.

Recognizing a Big Lie was a homework assignment in the civics class at my California high school, the Big Lie being a standard ploy in propaganda. For the Nazis, one Big Lie was that so-called Aryans were a supposed master race, somehow ordained to rule the world. The defeat of the Nazis put that fantasy to rest.

As World War II ended and the specter of the Cold War rose, with it came the threat that Russians, too, would make propaganda a weapon in their arsenal. And, so, high school students of my era learned to spot and counter malicious half-truths.

As an inoculation against lies coming from Russia at the time, we learned to spot the rudiments of such disinformation, the Big Lie among them. Propaganda, as we learned in my civics class, relies on not just lies and misinformation but also on distorted negative stereotypes, inflammatory terms, and other such tricks to manipulate peoples opinions and beliefs in the service of some ideological agenda.

Propaganda had played a major role in shaping the outlook of people ruled by the Axis powers. Hitler had argued that people would believe anything if it was repeated often enough and if disconfirming information was routinely denied, silenced, or disputed with yet more lies. Frankl knew well the toxicity of propaganda deployed by the Nazis in their rise to power and beyond. It was aimed, he saw, at the very value of existence itself, asserting the worthlessness of lifeat least for anyone, like himself, who fell into a maligned category, like gypsies, gays, Jews, and political dissidents, among others.

When he was imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps, Frankl himself became a victim of such systematic lies, brutalized by guards who saw him and his fellow prisoners as less than human. When he gave the lectures in this book a scant nine months after his liberation from the Turkheim labor camp, Frankl began his talk by decrying the negative propaganda that had destroyed any sense of meaning, human ethics, and the value of life.

As he and all those in his Viennese audience knew well, the Nazis had honed their propaganda skills to a high level. But the kind of civics lesson that taught how to spot such distortions of truth is long gone.