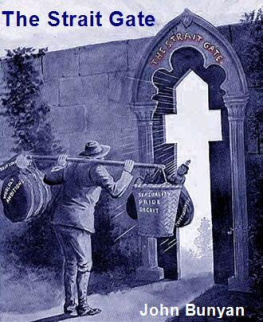

THE STRAIT GATE

The Strait Gate

Thresholds and Power in Western History

Daniel Jtte

YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven & London

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Calvin Chapin of the Class of 1788, Yale College.

Copyright 2015 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Walbaum MT type by Newgen North America

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015931017

ISBN 978-0-300-21108-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I am the door: by me if any man enter in, he shall be saved.

John 10:9

The door speaks.

Georg Simmel, Bridge and Door (1909)

CONTENTS

THE STRAIT GATE

INTRODUCTION

BY THE SPRING OF 1918, with the Great War in its final phase, the Central Powers, headed by Germany and Austria-Hungary, were facing certain defeat. Yet actual capitulation was slow in coming, and meanwhile, the burdens imposed on the population intensified. Public anger reached fever pitch in Germany and Austria-Hungary in early 1918, when officials ordered that all door handles and knobs be removed from homes and shops.

General provisions were already very scarce among both the general population and soldiers at the front. In particular, the scarcity of metalsindispensable for producing armamentsplaced a massive strain on the war effort. For several months, military leaders had been searching for new sources of industrial materials such as copper, brass, and iron. Church bells and kitchen pots were among the first to go, along with washbasins and oven doors. Now the people had to surrender their window handles and latches as well as their doorknobs, This sacrifice was one step too far.

Resistance was swift: in Vienna, the mayor and citizens protested against the new measures.

The critics position was clear: before taking such drastic action, the government and military should make every effort to requisition all useful metals from their own buildings and offices. Some of the proposed alternatives came close to lse majest: Even in the Reichstag we still have objects that we could sacrifice without much pain, such as the two statues of the Emperor standing in the dark in the vestibule, one opponent declared.

To date, this popular resistance to the confiscation of door handles and bolts has received almost no attention from historians. Granted, in the larger context of the war, it did not play a momentous role. The war dragged on until November 1918, likely aided by armaments made from recycled door fixtures. Afterward, metal door handles and bolts gradually returned.

Why did this measure trigger such an outcry? And why did it strike people as a kind of house-suicide? In our everyday lives, we tend to pay little attention to doors and their fixtures. We open and close them dozens of times every day; we regard them (if at all) as a means to an end, as mere devices for entering a building or room. But might not we, too, react with a great deal of discomfort and anxiety if we knew our doors and locks would soon stop working as they should?

This is a study of doors, gates, and keys and a history of the hopes and anxieties that Western culture has attached to them. Since my main focus is the premodern period, it may seem strange to have begun with a scene from World War I, but let us linger there for just a moment longer, specifically in 1915, three years before the confiscation of door fixtures became a political issue in German-speaking lands. At that time, a largely unknown writer in Prague by the name of Franz Kafka published a short story titled Vor dem Gesetz (Before the Law).door, the doorkeeper responds, but not at the moment. After some deliberation, the man accepts this and installs himself in front of it, waiting days and years to be admitted. He makes many attempts to enter, but the doorkeeper keeps him waiting. When finally his life is coming to an end, a radiance begins to emanate inextinguishably from the doorway. Desperate, the man asks why, in all these years, no one else has ever asked for admittance. In response, the doorkeeper roars in his ear: No one else could ever be admitted here, since this entrance was intended only for you. I am now going to shut it.

This parable, which Kafka later incorporated into his novel The Trial, is just two pages long in most modern editions, but it has given rise to hundreds of pages of interpretation. One reason for this is the archetypal situation that it depicts, which each of us has encountered at one time or another: the sense of helplessness, of powerlessness that comes from being denied entry or even being locked out, and standing at the doorway in vain.

In these examples, we see two facets of our cultures complex relationship to its doors and doorways: more than just a functional place of passage, the door is an object onto which we project our anxieties and hopes, as well as a site of power, exclusion, and inclusion. This is one of the reasons it was (and remains) a locus of multiple, conflicting meanings. And for this reason, historians need to avoid the temptation of over-simplification. Doors, for instance, can exist in more states than merely open or closed, and even the meaning of an open or closed door is not constant. It has been observed that doors In principle, this is correct; however, the content of the message and the way we perceive it are always contingent upon the specific situation and its sociocultural context. Thus, holding open a door is, in many situations, still considered a particular sign of respect. In the same vein, a door that is intentionally left open is often understood as a gesture of hospitality, an invitation to enter, or at least a sign of readiness to communicate. It is no coincidence that we speak figuratively of an open house for an occasion when a building or institution is open to a large number of people to whom entrance is otherwise prohibited. Significantly, the term open house and its corresponding German and French expressions, literally meaning day of the open door (Tag der offenen Tr; journe portes ouvertes), have entered the common lexicon precisely because they describe an exception to the rule, highlighting the infrequency of this situation: usually, the doors of a public building are open to the general public only one day in the year. (In the American context, open house can also refer to a different but similarly exceptional event: the showing of a house that is for sale.) However, an open door can also have negative connotations: a door we cannot close, or one that stands open for no obvious reason, will arouseas during World War Iour mistrust, or worse, our fear.

Conversely, closed doors often signal protection to those who are inside and enable withdrawal from the outside world. Closing a door sends the message that one wishes to retreat to the interior of a dwelling and not be disturbed. As

Any kind of dwelling, be it a Stone Age cave, a medieval house, or a modern apartment, is marked by the same tension: it can be a place of protection, but it also has the potential to become a trap. The idea of not being able to open a door from the inside is the stuff of nightmares. And indeed, in emergency situations, the ability (or inability) to open a door from the inside can mean the difference between life and death. For this reason, public buildings are required to have emergency exits and, in many cases, panic exit devices; private buildings are sometimes subject to similar regulations. But even when lives are not at stake, the loss of (individual) control over the opening of a door threatens our sense of personal freedom and essentially embodies the legal definition of imprisonment. Prison doors have no handles, and indeed millions of prison inmates around the world, irrespective of their crimes or backgrounds, are ultimately connected by a shared fate: the inability to open the doors behind which they live out their sentences. This feeling of powerlessness is a core and particularly humiliating aspect of the prisoners punishment.

Next page