Prologue: On Transmission

T HE V ASTNESS O PENS

E VERY STORY of spiritual awakening is a story of transmission. kyamuni, in a prior life as the youth Sumedha, bowed down before the Buddha of that age, Dpakara. He was so transformed by the dual transmission of Dpakaras own presence and hearing the word buddha that he vowed to become a buddha himself. Moses received transmission of Gods word and experienced Gods blazing power in a bush; these visions still hold together a community of worship. Christ, as Word, was himself a body of transmission. St. Teresa of Avila became the bride of Christ and in this way received Christs most intimate knowing. Rumi, the great Sufi mystic, communed endlessly with the Friend. In every instance, transmission is how the inconceivable makes itself known.

Spiritual openings like these can, in the Tibetan perspective of this book, all be appreciated as occasions of transmission, for transmission is a dynamic that is central to spiritual development, and especially to the flourishing of mystical or esoteric understanding. Rumi says that the holy ones are theatres in which the qualities of wisdom-reality are on display. That display is also a transmission. Through the ages, transmission has rained down in different streams, demonstrating again and again that the expanse of wisdom is infinitely creative.

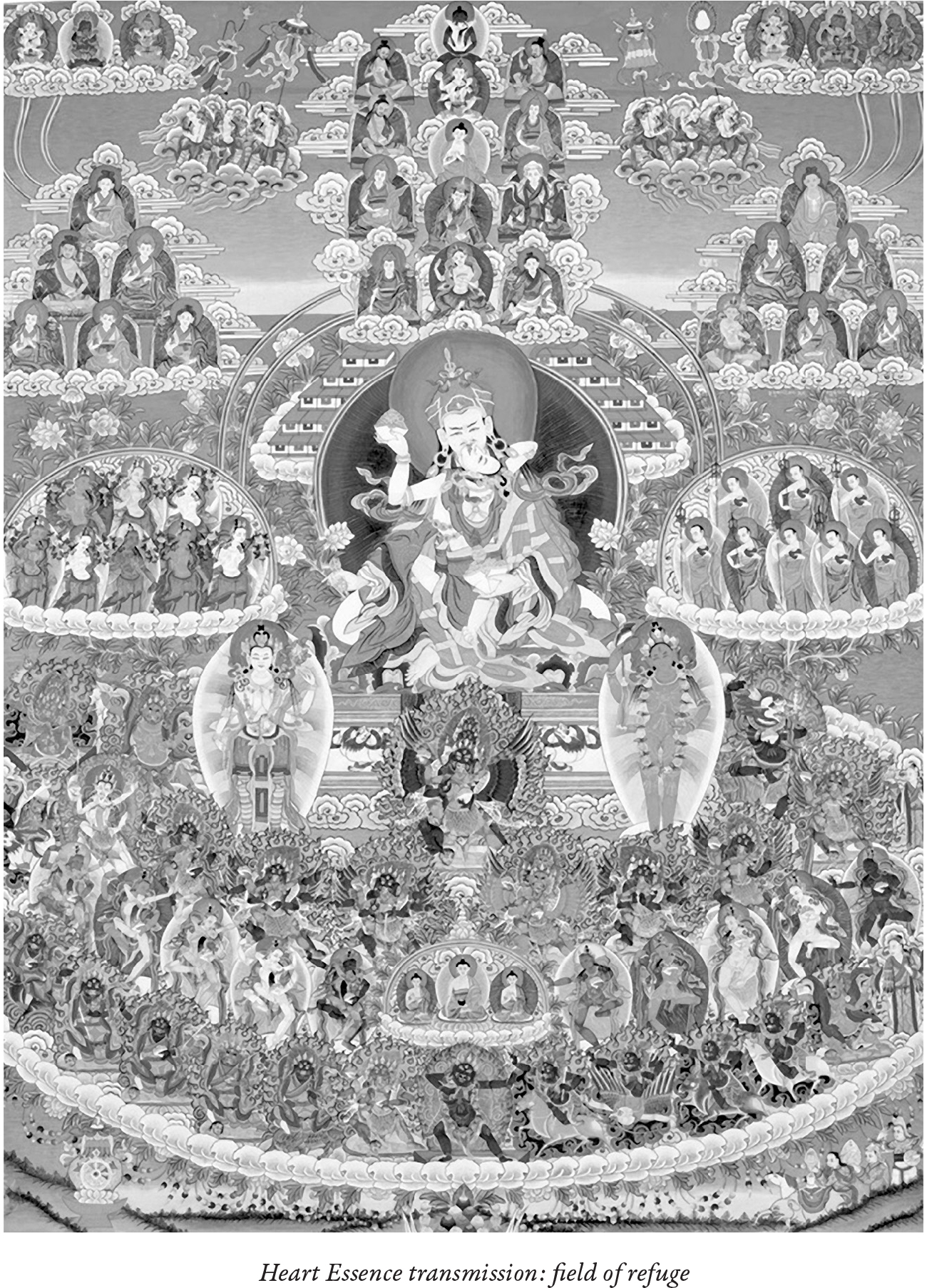

Guru Rinpoche, the great eighth-century initiator of Tantric practice in Tibet, received transmission from Garab Dorje, the first human practitioner of Dzogchen. Garab Dorje received transmission from the Diamond Being, Vajrasattva, himself. And Vajrasattva was the first, hence the most subtle and purifyingly powerful, expression of the pristine and simple reality that is Samantabhadra, whose name means All Good and who is described as the primordial Buddha and source of Dzogchen transmission. Practitioners resonate with that celebration even when we do not fully understand it.

Buddhas are continuously transmitting through their presence, their gestures, and their speech and sacred scriptures, as well as through their images. Every seeker participates in the great ongoing mystery and revelation that transmission makes available. For transmission is wisdom manifesting from the unmanifest. Transmission is also how teachings move from teacher to student, across generations and across landscapes. Such teachings are not mere words, certainly, nor mere ideas, though they encompass both. Since Dzogchen teachings are experienced as expressions of and arising from reality, they are most fully communicated in the living presence of persons who embody them. These persons teach while themselves dwelling in an awareness of that reality.

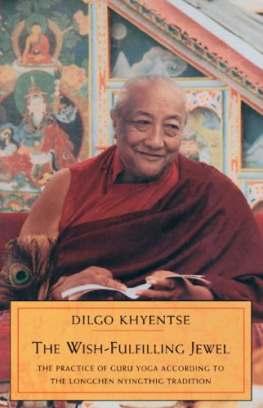

Thus, transmission is a moving stream. It is not something inanimate, like a stone, not the sort of thing that is the same wherever one finds it. With transmission it matters very much from whom you receive it, and where, and how. The lineage and realization of the bestower, as well as ones own responsiveness to him or her and ones own state at the time, all have an impact on the precise nature of transmission. This is one reason why in Tibet there are so many textual transmissions of, for example, the foundational practices. All of them express very similar concepts. The differences lay not so much with words or meaning as with lineage and the precise channel of access to their blessings. Texts of transmission are treated with the same respect as living holders of transmissionnever placed on the floor, stepped on, or used as furniture. One has a living and interactive relationship with them. Transmission, as we understand it here, is something alive, something with which one interacts, not another item of consumption. Thus, a rigorously traditional lama like Adzom Paylo Rinpoche allows no recording of even his most basic and exoteric teachings.

In the West, where information is increasingly a commodity for sale and where teachings are easily available through books, the internet, CDs, and videosmeaning that such teachings and information are often exchanged through transactions among strangersit is easy to forget that traditionally, and for very important reasons, teaching happens in relationship. If you want to connect deeply with any practice, by all means find a teacher who can give the kind of transmission that by definition cannot be fully present in a book.

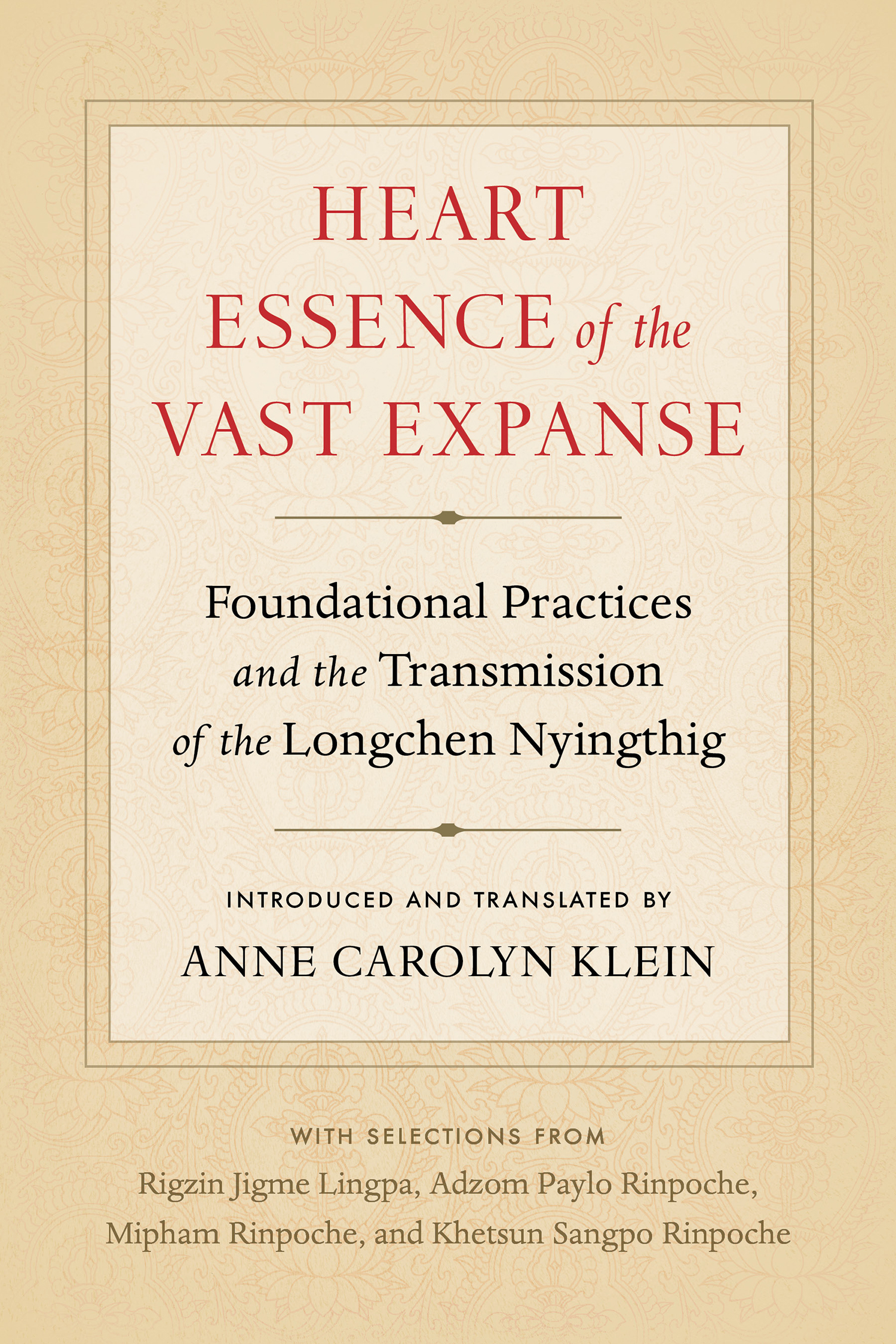

Still, this is a book about transmission. It arises from and participates in transmission too. The music, the ancient words, the images, all carry some part of it. You hold in your hands a text transmitted spontaneously in the eighteenth century to Rigzin Jigme Lingpa through his visionary communication with well-known figures of the eighth and fourteenth centuries: Guru Rinpoche, Vimalamitra, and Longchen Rabjam. Jigme Lingpas text on the Longchen Nyingthig foundational practices is the first text translated herein. The second text is a more recent transmission from the same lineage source, a condensation of Jigme Lingpas text by Adzom Paylo Rinpoche, who received transmission through the Adzom branch of Heart Essence