I NSIDE THE G RASS H UT

Clearly and beautifully links the life of this renunciate mountain monk to our own complex, multitasking, engaged, and over-involved lives. He brings this poem to our lives, just as they are.

SHARON SALZBERG, AUTHOR OF REAL HAPPINESS

Written from the inside out, this wonderful book explores Zen Master Shitous marvelous and revelatory poem Song of the Grass-Roof Hemitage. The language and sense of immediacy make Shitous work transparent to all.

JOAN HALIFAX, FOUNDING ABBOT, UPAYA ZEN CENTER

Easy and pleasant to read, with plenty of wit, and many examples from daily life. Theres humor, deft turning of phrase, even some paradox and poetry.

NORMAN FISCHER, AUTHOR OF TRAINING IN COMPASSION

Written not just for Zen practitioners, this lovely book offers insights and encouragement to all who seek to live in the simplicity of the present moment.

JANET ABELS, AUTHOR OF MAKING ZEN YOUR OWN

A clear presentation of Zen tradition and practice. Striking is the personal and serene tone of the writing, of the instructive exposition, which infuses the book with a living pulse andwhat I will dare to call herethe very essence of Zen.

MIKE OCONNOR, TRANSLATOR OF WHERE THE WORLD DOES NOT FOLLOW

A wonderful guidebook on the path to being a wiser and kinder human being.

ELLEN BIRX, AUTHOR OF SELFLESS LOVE

Table of Contents

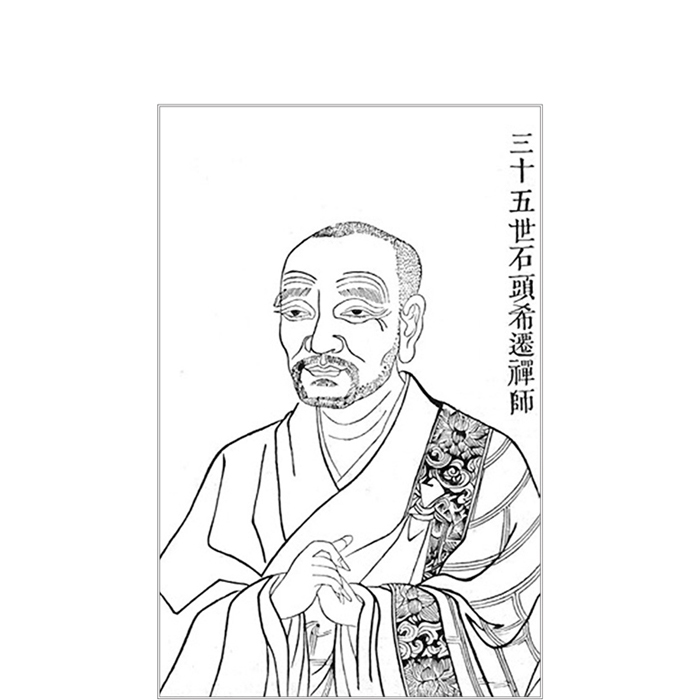

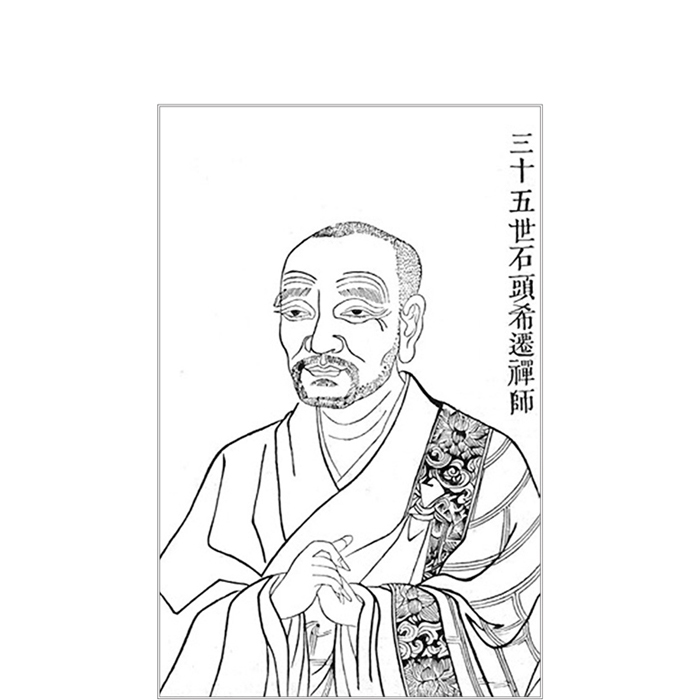

The important early Zen master Shitou is a major ancestor in the Chinese Caodong, or Japanese Soto, lineagea lineage that is now very significant in the spread of Buddhism to the West. He is best known for his poem Harmony of Difference and Sameness, or Sandokai in Japanese, which presented the underlying philosophy, imagery, and dialectical polarities foundational to all of Zen Buddhism but especially significant in the Caodong/Soto lineage. This poem by Shitou is a clear precursor for the poem Song of the Jewel Mirror Samadhi, attributed to the lineage founder Dongshan in the following century.

Shitou is said to have lived from 700 to 790. His poem Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage, the central text for this book, presents not the philosophy of Zen, as Harmony of Difference and Sameness does, but instead offers a clear, helpful model for its actual practice, and for how to create a space of practice. Shitou built and resided in his grass-roof hermitage near his larger temple, where he trained numbers of students. His hut was his literal practice place, but it also serves as a metaphor for all Zen practice spaces. Lines from this Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage are mentioned by later Soto figures such as Dongshan, Hongzhi, and Dogen and can be found embedded in koan collections such as the Blue Cliff Record and the Book of Serenity. But the poem as a whole was relatively neglected, certainly compared to the more celebrated Harmony of Difference and Sameness. I came across some reference to the second poem in biographical materials about Shitou and translated it in 1985 together with my friend Kaz Tanahashi; it was first published by the Windbell journal of the San Francisco Zen Center.

I am very pleased that Ben Connelly has chosen to use Shitous Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage as an inspiration for his fine, personal practice reflections in this book. I am also very pleased that this poem is chanted at the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center where Ben practices, as it is in my temple in Chicago. This illuminating poem is now finally receiving some of the attention it richly deserves. It had not previously been part of any liturgy to my knowledge, and I am grateful to have helped promote its reemergence. Along with Ben I heartily recommend chanting the Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage; my students have found it very inspiring.

A story about Shitou worth recounting relates that one of his main disciples once asked him about the essential meaning of Buddhadharma. Shitou responded, Not to attain, not to know. The student then asked whether there was any other pivotal point, and Shitou said, The wide sky does not obstruct the white clouds drifting. The flavor of Shitous practice is not to worry about any attainment or accomplishment, or even to know anything. This is difficult for many contemporary students trained, in our acquisitive consumerist society, to accumulate accomplishments. Many students also think they need to figure out some rational understanding of Zen sayings. But as Shitou says about himself, This mountain monk doesnt understand at all. Shitou encourages a spacious sense of practice, even in his small hut that includes the whole wide sky. But in this open-hearted space, the drifting clouds of practice are meaningful and not at all obstructed.

I especially appreciate Ben Connellys taking on and opening up the many environmental implications of the Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage. Shitou realized that his hut, and each of our own spaces of practice, includes the entire world. We are each indeed deeply interconnected to the whole of nature. As Ben elaborates, Shitous living lightly on the earth has major repercussions informing the Buddhist teaching of nonself, and how to see beyond our usual habitual grasping after self-identity.

I am tempted to comment myself on many of the numerous wonderful, rich lines in the Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage. But I will leave that to Ben Connelly, and for the reader, to proceed. However, I must say that Shitous Turn around the light to shine within, then just return marvelously contains all of Buddhist practice and its primary rhythm in one line. Further, Shitous line Let go of hundreds of years and relax completely is a wonderful antidote to significant, harmful misunderstandings of Zen practice in our time. The point of Zen practice is to relieve suffering and promote liberation for all beings. Shitou tells us that the way to actively express such universal liberation involves relaxing completely. Please consider this thoroughly.

And please enjoy Shitous song, and the many helpful harmonies that Ben Connelly has added for you.

Taigen Leighton

September 2013

Taigen Dan Leighton is the author of Zen Questions: Zazen, Dogen, and the Spirit of Creative Inquiry and Faces of Compassion: Classic Bodhisattva Archetypes and Their Modern Expression, as well as the cotranslator of Dogens Extensive Record. He is the Dharma teacher at the Ancient Dragon Zen Gate in Chicago.

Thank you for being here with me. Through words, we can be together right now across space and time. Through this book, we can spend a little time with an old monk, his poem, a great tradition, and each other.

I encourage you to give yourself to this time. This particular moment is an opportunity for each of us to give our wholehearted attention to what is here: the air we breathe, the words we read, the sensations in our body, the sounds around us, and the activity of our minds and our hearts. This is a way of being to which we can always aspire.

Remember that turning your wholehearted attention to this text, or to whatever you happen to be doing, can be of benefit to every beingeven if its not obvious how. This may seem like a strange ideaor a very familiar onebut it is essential to the Buddhist tradition. Our study of the Dharma, and our practice of giving ourselves to each moment, should always be done with the intention to somehow lift the overall well-being of the world.

Next page