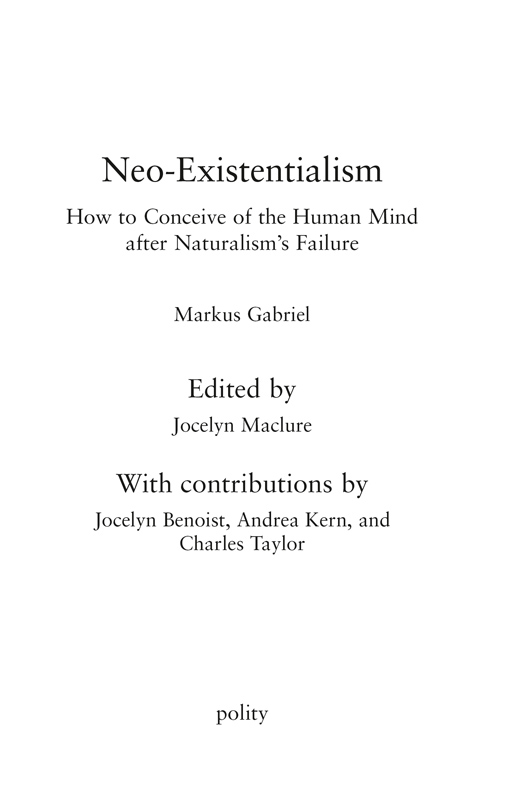

Copyright page

This collection Polity Press 2018

Introduction copyright Jocelyn Maclure 2018

Chapter 1 & 5 copyright Markus Gabriel 2018

Chapter 2 copyright Charles Taylor 2018

Chapter 3 copyright Jocelyn Benoist 2018

Chapter 4 copyright Andrea Kern 2018

First published in 2018 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3247-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3248-3 (pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 10.5 on 12 pt Sabon

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN

Printed and bound in Great Britain, by Clays Ltd

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Introduction

Reasonable Naturalism and the Humanistic Resistance to Reductionism

Jocelyn Maclure

Markus Gabriel is one of the most exciting minds among the new generation of academic philosophers. He defends bold views on large metaphysical questions. In his previous work, he argued that the abuse of constructivism in ontology and epistemology called for a renewed kind of realism centered on the plurality of domains of objects or fields of sense that make up our reality. His work is based on an impressive command of a variety of past and present philosophical traditions. There is no sharp divide, for him, between philosophy and its history. And, as he points out in the opening chapter of this volume, he views the continental/analytic distinction as nonsensical and debilitating.

Gabriel adds his voice to a distinguished tradition of humanistic scholars who worry about the overreach of scientific discourse in our understanding of human reality and experience. A strand of that tradition finds its root in German philosophy, as exemplified by the responses gathered in this volume. This is not something that was planned in the design of this book when I reached out to a number of potential commentators, but it turned out that Charles Taylor, Jocelyn Benoist and Andrea Kern all implicitly or explicitly draw upon traditions such as idealism and phenomenology to support Gabriels take-down of naturalism in analytic philosophy of mind. Charles Taylor is a long-time critic of scientism and reductive naturalism. In her work in metaphysics and epistemology, Andrea Kern is articulating a brand of neo-Aristotelianism influenced by Kant and German idealism. All three, like Gabriel, have decidedly moved beyond the analytic/continental divide in contemporary Western philosophy.

In the piece which is the cornerstone of this volume, Gabriel challenges the hegemony of naturalism in analytic philosophy of mind. He starts from the classic problem of how the mind fits in the natural world. How can physical and biological processes which are not, as far as we can tell, conscious give rise to mental states such as desires, beliefs, and intentions? Once we give up, on the basis of our best natural sciences, the belief in an immaterial soul, how do we explain our conscious subjective experience and how does it map onto everything that we know about the physical world? Given that Cartesian substance dualism is no longer an option, the obvious temptation is to reduce the mental to more basic natural properties, such as brain processes, which are themselves explainable in terms of physical laws, mechanisms, and properties. But since it is not clear how studying various regions of the brain and neural activity is supposed to reveal what is a subjective experience, such as experiencing a first kiss with someone on whom you have a crush, many wonder whether we are confronted with a hard problem that may never be solved by the natural sciences, the neurosciences included.

Gabriel associates naturalism, among other things, with the choice to see the mind as a natural kind and to reduce it to physical mechanisms. He thinks this choice is misguided. He wants to put pressure on the entire framework which made of naturalism an overarching speculative metaphysics rather than a sound approach to the study of the natural world. In contrast, he sketches a position that he calls Neo-Existentialism, which is:

the view that there is no single phenomenon or reality corresponding to the ultimately very messy umbrella term the mind. what unifies the various phenomena subsumed under the messy concept of the mind after all is that they are all consequences of the attempt of the human being to distinguish itself both from the purely physical universe and from the rest of the animal kingdom. In so doing, our self-portrait as specifically minded creatures evolved in light of our equally varying accounts of what it is for non-human beings to exist. ()

We may wonder, as Taylor does in his commentary, whether the reference to existentialism is the best way to characterize the view that he is putting forward and to bring together the philosophers from whom he is drawing inspiration. Gabriels Neo-Existentialism is much broader than the philosophical views expounded by Sartre and de Beauvoir after the Second World War. Some of the preeminent early figures of the movement such as Merleau-Ponty and Camus later explicitly rejected the label. Neo-Existentialism appears to include elements drawn from what is sometimes called philosophies of consciousness or subjectivity, German idealism, phenomenology, hermeneutics (as applied to selfhood, or narrative theories of the self) and philosophies of existence.

Gabriel clearly sides with those who reject the identity theory between the brain and the mind, as well as with those who think that the mind is not only in the head. I see him as a philosophical anthropologist who draws our attention to the inescapably cultural or social dimension of the mind. The mind is the result not only of the neural activity which makes consciousness possible but also of the self-interpreting, meaning-making, and collective symbolic activity which is the trademark of our species. As Gabriel puts it, We should not expect that all phenomena which have been described from the intentional stance over the millennia, and for which we have some kind of record of documenting an inner life, could possibly be theoretically unified by finding an equivalent natural substratum for them (

That being said, Gabriels Neo-Existentialism appears to be ambiguous with regard to the exact way to think about the brainmind relationship. On the one hand, he clearly states that he does not want his view to deny what has been firmly established by the natural sciences. He thereby accepts that having a certain kind of brain is a necessary condition for having a mind. He does not challenge the fact that all mental events have brain correlates. On the other hand, he asserts that The notion that mind has to fit into the natural order is nothing but the most recent mythology, the most recent attempt to fit all phenomena that are relevant to human action explanation into an all-encompassing structure ().

Next page