INTRODUCTION

E very arrival is also a return. In the early history of the maritime exploration of planet Earth, the moment of landfall after a long sea journeyeven if it was to an unknown shore, with all its dangerswas usually a huge relief, because it was a return. After weeks of dwindling supplies, tropical heat, water rationing, scurvy, and maybe a mutinous muttering below decks, the sight of land gave as much comfort to the soul as the feel of solid ground could the body. Land, any land, was an oasis of possibility in a heaving desert of salt.

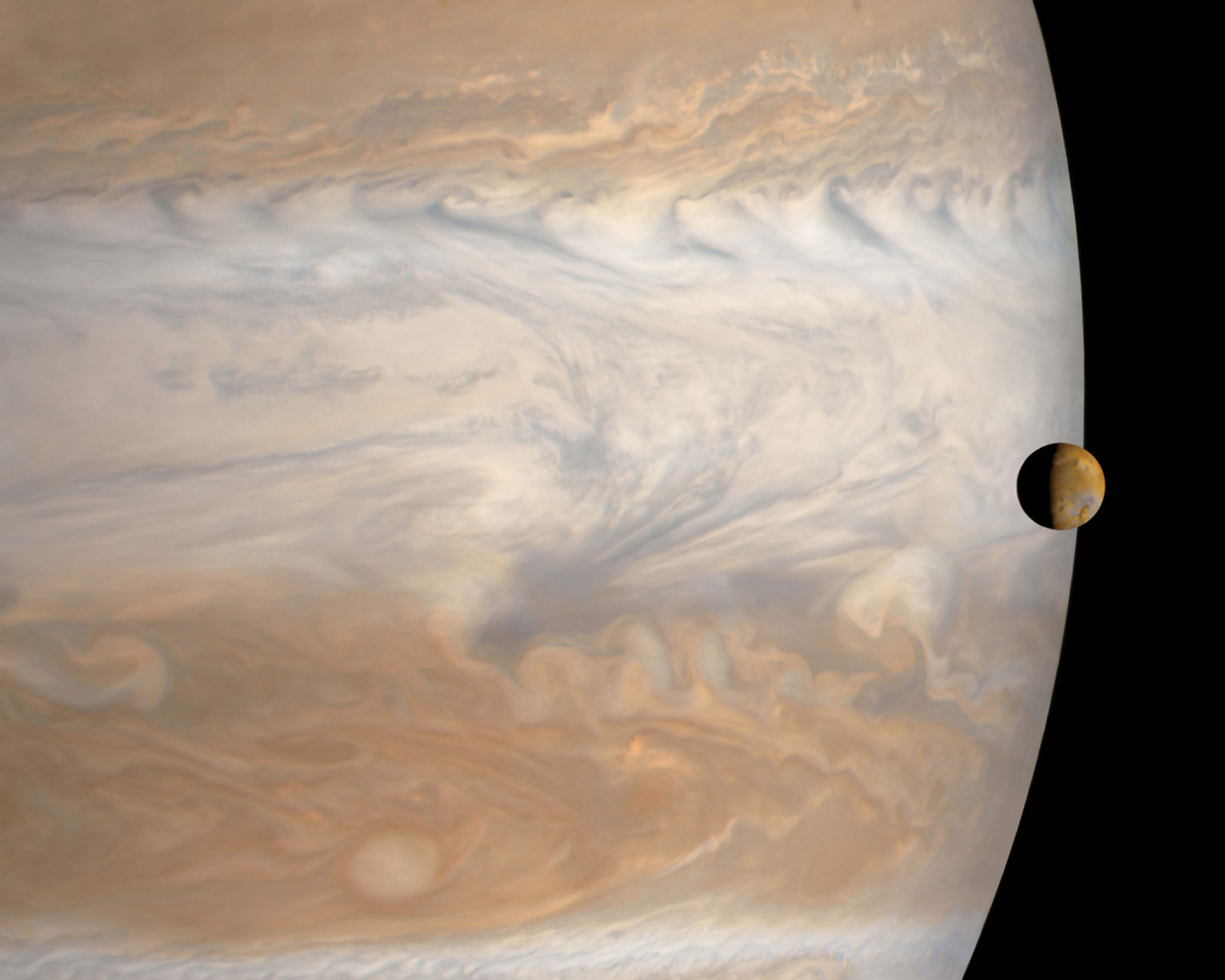

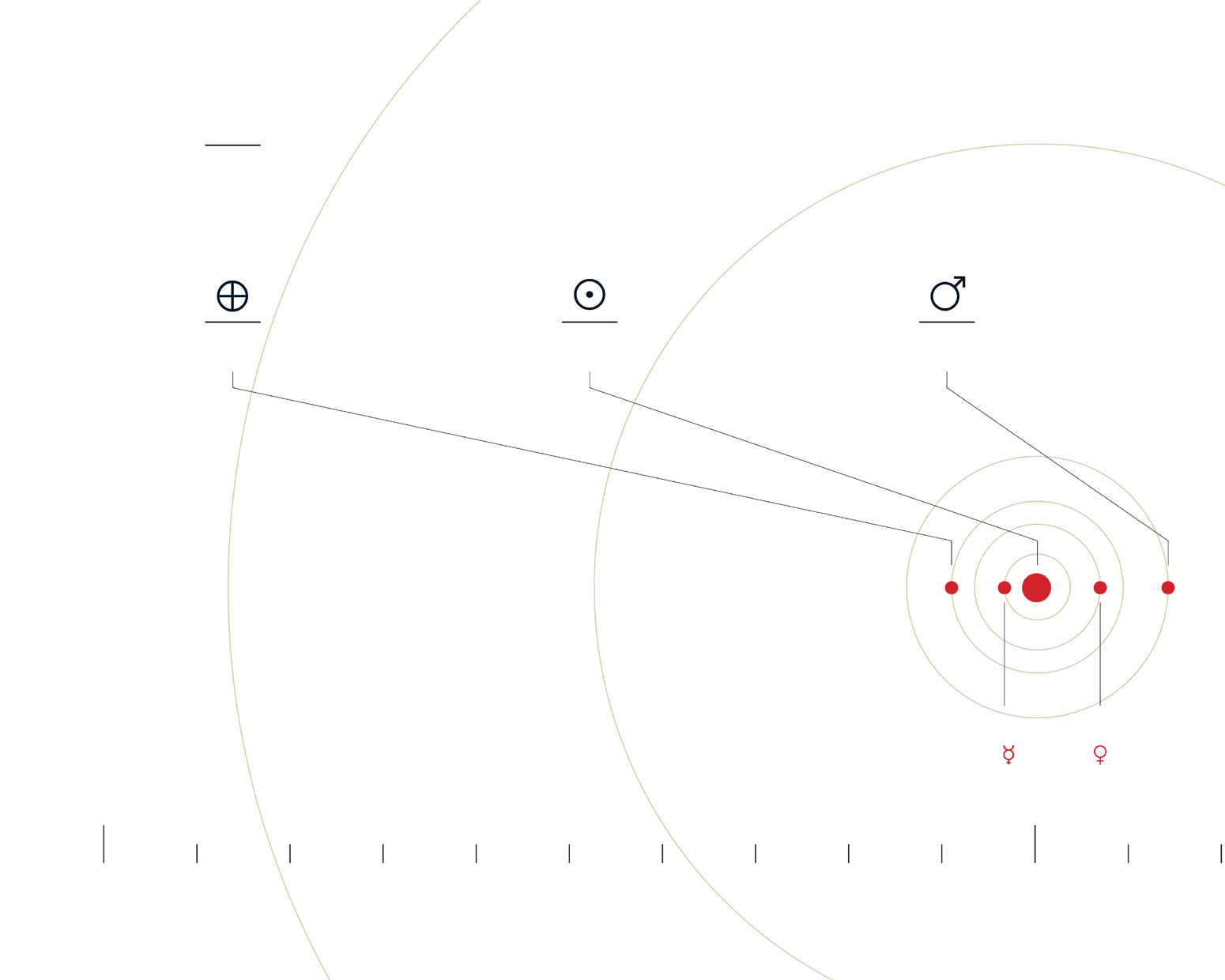

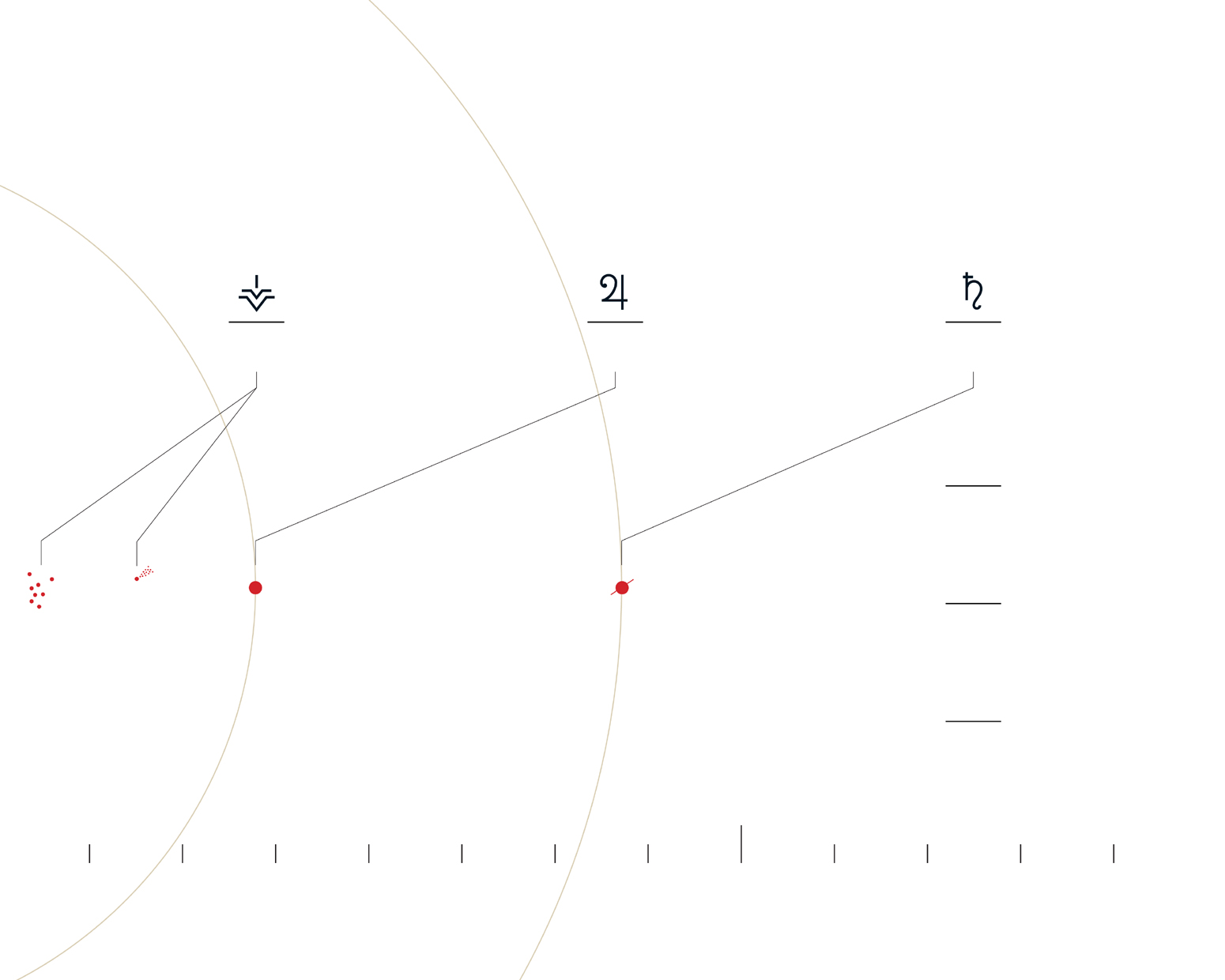

And the same goes for the arrival, in the blackness of space, to any place . Its always a returnto something rather than nothing. Even if were told by theoreti- cal physics that the vacuum between worlds, which would seem the ultimate nada , is actually a teeming, seething vortex of virtual particles and crisscrossing ener gies, thats just something a theoretical physicist said. To our senses, the void of interplanetary spacethe same emptiness that reigns between the stars, itself an extension of the echoing chasm between the glittering galaxies themselvesis a vast sea between extremely rare islands. Thats as true if were looking up without technological mediation on a clear summer night, or observing through a telescope, or channeling our senses via the imaging systems of our distant robotic explorers.

Space is the best expression of zero in the realm of the physical. And it follows that anything elsebe it a gas giant world with dozens of moons in tow; a terrestrial planet with oceans, deserts, and sentient inhabitants; or a tumbling asteroidis a one. We ourselves, each of us seated at the controls for the duration of our human existence, are miraculous individual somethings , rather than unitary undifferenti- ated nothings . It follows that arrival at any place that qualifies as a place, rather than the space between, is the return of matter to matter, on the most primal level.

And so, planetfall .

The great French psychoanalyst of fire Gaston Bachelard once wrote, Even a minor event in the life of a child is an event in that childs world and thus a world event. Futurist Arthur C. Clarke evidently agreed with him, though maybe not in exactly the way the philosopher meant, because for Clarke all world events were in principle generated by a profoundly immature race. As the title of his finest novel , Childhoods End , indicates, in the Clarkean universe Homo sapiens , far from being the Wise Man of the Latin, hadnt even reached adolescence let alone adulthood. On an evolution- ary timescale, in fact, it is likely that we are an interim species. We are the miss- ing link, Clarke insisted to me, sitting in the sunny garden of his Hikkaduwa beach house in the spring of 2001a year that had played a significant role in his career, albeit more than three decades previously.

As someone who himself came of age between the two great world wars of the twentieth century, Clarke had plenty to back up his position with. The childhood ______

motif recurs throughout his work, most strikingly in the concluding shots of his 1968 collaboration with Stanley Kubrick, 2001: A Space Odyssey , in which an embryonic Star Child looks down on a serenely beautiful blue-white planetthe very definition of an oasis in space. The original plan had been for the child, as a kind of harbinger of evolutions next step, to go around destroying the nuclear bombs that, it was assumed, would be jostling each other in Earths orbit by the year 2001. But Kubrick, who always went for mystery where Clarke argued for specificity, judged this as being too similar to the end of his previous film, Dr. Strangelove . So the orbiting Star Child simply rotates in the final shot of the film, gradually making eye contact with the audienceand leaving us with a profoundly ambiguous expression worthy of Leonardo.

Despite his seemingly bleak assessment of the human condition, Clarke pos- sessed an innate optimism that we would ultimately grow up and build a ladder to the starsmaybe even a space elevator. His optimism, which in 2001 leavened Kubricks congenital pessimism in much the same way (and during the same period) that McCartney leavened Lennon, was in turn influenced by Russian visionary Konstantin Tsiolkovskys powerfully programmatic statement: Earth is the cradle of the mind, but humanity must not remain in its cradle forever.

This, the great utopian credo of the space age, has been overquoted by space- flight freaks, but for good reason. It really does state the terms of our existential situation. Having arisen through the millennia to a state of consciousness, we have now reached the unavoidable conclusion that we live not just on Earth but within a vast Universe that, despite its scale, is increasingly accessible to us, and we really do face the choice between staying put or venturing forth. Whats it going to be?

Tsiolkovskys words are frequently translated as Earth is the cradle of Man , but his language made it clear that he was speaking in broader terms, of the mind mak- ing the epochal leap into the cosmos, not just the oxygen-chugging vehicle it rides in. I make this point because, in true Russian fashion, the patron saint of cosmism was pointing the way to the development of a broader human consciousness about the Universe, however important the actual propulsion of human beings into space. The soul must precede the body, or follow the body; in any case, the soul must be involved.