Contents

Guide

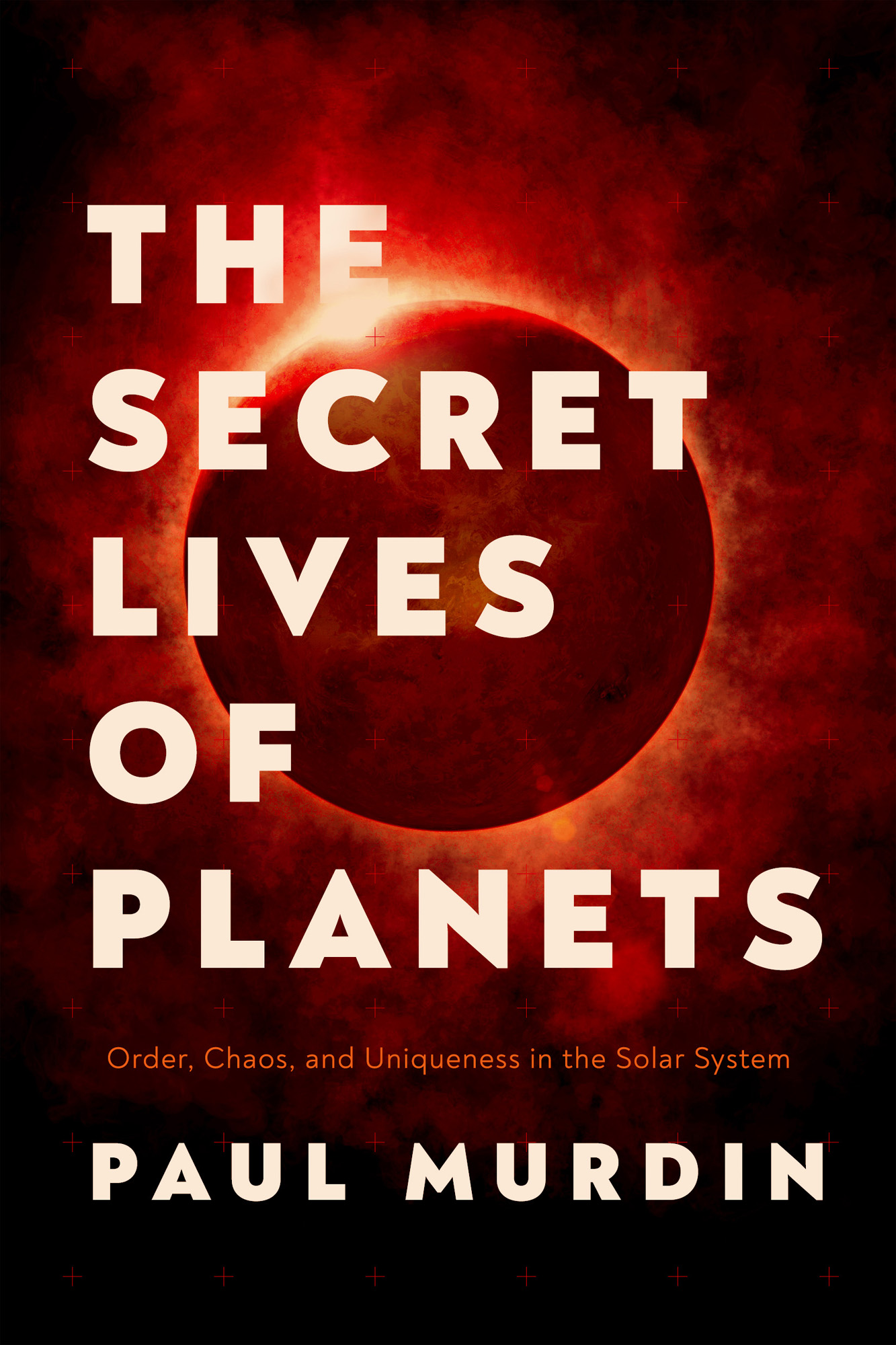

THE SECRET LIVES OF PLANETS

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Paul Murdin

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition October 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-64313-336-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-64313-397-3

Jacket design: Brock Book Design Co. / Charles Brock

Jacket photo: Adobe Stock

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

www.pegasusbooks.com

To the engineers and scientists who have shown us far worlds

CHAPTER 1 Order, chaos and uniqueness in the solar system

If crime fiction is to be believed, English village life is in the main quiet and regular, an ordained series of small and unimportant events punctuated by drama that reveals secrets hidden behind the lace curtains at the windows of outwardly respectable people. The village day has a regular roster of visits by the postman and the electricity-meter reader, the month has a schedule of meetings of the Bridge Club and the church choir, the year has an annual cycle for the Flower and Produce Show and the Nativity Play. But the colonel is then found in his bed, stabbed, it turns out, by a former partner in his shady business dealings in the Far East. The verger is found hanging from the ropes of the church bell, having thus been removed by his ex-wifes lover from the list of beneficiaries of a will. The postmistress is on the track of the writer of poisoned-pen letters until she is drowned in a well, her bicycle lying nearby on the village green. The quiet life of the village is disrupted and the secrets that lie under its surface are exposed.

Novels like Agatha Christies are fictionalised versions of real life. We would like to think of life as orderly and structured, but we learn about, and occasionally are participants in, chaotic events like car accidents, illnesses, hurricanes, floods and terrorist attacks.

Likewise, we may have the impression that the solar system is constant and perfectly regular like a clock, or a planetarium instrument. On a short timescale it is. But, seen in a longer perspective, the planets, and their satellites, have had exciting lives, full of drama. As in human lives, some changes in the lives of the planets are evolutionary and gradual, corresponding in us to the natural processes of growing up. Sometimes, they are life-changing, like catastrophic accidents in human lives, that throw a planet into a new trajectory, metaphorically or literally. The effects of the dramatic events leave their traces on the appearance and structure of the planets, and part of the job of planetary science is to infer what happened. The present is the key to the past, wrote the nineteenth-century Scottish geologist Archibald Geikie about the Earth. As the Earth, so all the planets.

The vision of the solar system as a clock reached its pinnacle in the eighteenth century. The fundamental geometry of the solar system as a system of planets in orbit around the Sun was surmised by the Polish cleric Nicolaus Copernicus in 1543, and demonstrated to be so by the Italian physicist Galileo Galilei through his discoveries with the telescope in 1610. Empirical laws describing mathematical properties of the planetary orbits, such as the fact that they are ellipses, were established by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler between 1609 and 1619. Drawing together all these discoveries, the mathematician Isaac Newton put forward in 1687 the underlying physical principles of planetary motion in his book known as Principia, with its brilliantly simple and exactly formulated notion of a Law of Gravitation.

Newtons model of the solar system held that it was a thoughtful work of mathematics. He asserted in 1726 that the wondrous disposition of the Sun, the planets and the comets, can only be the work of an all-powerful and intelligent Being. According to Newton, God orchestrates the movements of the solar system, and controls them through the Law of Gravitation as the planets progress towards their future.

This model of the Universe developed further in the hands of Newtons successors, notably the French physicist Pierre Simon Laplace. He demonstrated mathematically, from Newtonian principles, that the solar system was stable. The planets orbited in a flat disc around the Sun and they would continue to do so indefinitely. He thought therefore that, once created, the solar system would last in the same form for ever. The solar system was something eternal that developed from its beginnings with inevitability.

Laplace was able to express the certainty of physics with certainty of belief:

We ought to regard the present state of the Universe as the effect of its antecedent state and as the cause of the state that is to follow. An intelligence knowing all the forces acting in nature at a given instant, as well as the momentary positions of all things in the Universe, would be able to comprehend in one single formula the motions of the largest bodies as well as the lightest atoms in the world, provided that its intellect were sufficiently powerful to subject all data to analysis; to it nothing would be uncertain, the future as well as the past would be present to its eyes.

In an influential book, Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, published as the eighteenth century opened, the theologian William Paley described the construction of the planetary system:

The actuating cause in these [planetary] systems, is an attraction which varies reciprocally as the square of the distance: that is, at double the distance, has a quarter of the force; at half the distance, four times the strength; and so on So far as these propositions can be made out, we may be said, I think, to prove choice and regulation; choice, out of boundless variety; and regulation, of that which, by its own nature, was, in respect of the property regulated, indifferent and indefinite.

Paley likened the solar system (and human anatomy, and other natural phenomena) to an intricate, well-made watch. He inferred from this that, just as a watch was made in a particular way by a watchmaker, natural phenomena were made by God, the Divine Watchmaker. This is the Teleological Argument for the existence of God (otherwise known as the Argument from Design). In brief, the argument is: natural phenomena work well; they fit together intricately as if designed; there must have been a Designer; the designer is God. Paley reasoned that, if we find a watch lying on the ground,

the inference, we think, is inevitable; that the watch must have had a maker; that there must have existed, at some time and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers, who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use.

It was a reassuring model of the Universe: we live in a harmonious world designed by the Supreme Being. Paley applied this idea to the solar system of planets, but he concentrated also on human anatomy the human eye looked as if it had been made to a design and God was that designer. The model persists in modern times, and Paleys book is still quoted.