SHEFFIELD STUDIES IN AEGEAN ARCHAEOLOGY

ADVISORY EDITORIAL PANEL

Professor Stelios ANDREOU, University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Professor John BARRETT, University of Sheffield, England

Professor John BENNET, University of Sheffield, England

Professor Keith BRANIGAN, University of Sheffield, England

Professor Jack DAVIS, University of Cincinnati, USA

Professor Peter DAY, University of Sheffield, England

Dr Roger DOONAN, University of Sheffield, England

Professor Paul HALSTEAD, University of Sheffield, England

Professor Caroline JACKSON, University of Sheffield, England

Dr Jane REMPEL, University of Sheffield, England

Dr Susan SHERRATT, University of Sheffield, England

Published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by

OXBOW BOOKS

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE

and in the United States by

OXBOW BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083

Oxbow Books and the individual contributors 2017

Paperback Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-295-2

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-296-9 (epub)

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-297-6 (kindle)

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-78570-298-3 (pdf)

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sherratt, Susan, editor. | Bennet, John, editor.

Title: Archaeology and Homeric epic / edited by Susan Sherratt and John Bennet.

Description: Oxford & Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, 2016. | Series: Sheffield studies in Aegean archaeology | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016040020 (print) | LCCN 2016044861 (ebook) | ISBN 9781785702952 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781785702969 (epub) | ISBN 9781785702976 (mobi) | ISBN 9781785702983 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Archaeology--Greece. | Homer--Influence. | Epic poetry, Greek--History and criticism. | Civilization, Homeric.

Classification: LCC DF78.A644 2016 (print) | LCC DF78 (ebook) | DDC 938--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016040020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed in the United Kingdom by Hobbs the Printers Ltd

For a complete list of Oxbow titles, please contact:

UNITED KINGDOM

Oxbow Books

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

Email:

www.oxbowbooks.com | UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Oxbow Books

Telephone (800) 791-9354, Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casemateacademic.com/oxbow |

Oxbow Books is part of the Casemate Group

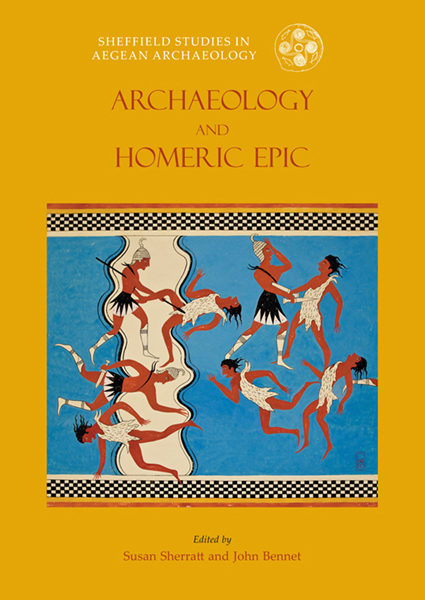

Front cover: Reconstruction by Piet de Jong of battle scene in Hall 64 at Pylos (Lang 1969: col. pl. M). Courtesy of The Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati and American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Pylos Archive, Piet de Jong Collection of Watercolors. Photo Jennifer F. Stephens and Arthur E. Stephens.

Contents

Anthony Snodgrass

Oliver Dickinson

Johannes Haubold

Susan Sherratt

Jack L. Davis and Kathleen M. Lynch, with a contribution by Susanne Hofstra

Diamantis Panagiotopoulos

Alexander Mazarakis Ainian

Stephanie Dalley

Margaret H. Beissinger

Roderick Beaton

Paul Halstead

List of Contributors

RODERICK BEATON

Centre of Hellenic Studies, Kings College London

JOHN BENNET

Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield

MARGARET H. BEISSINGER

Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, Princeton University

STEPHANIE DALLEY

Oriental Institute, University of Oxford

JACK L. DAVIS

Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati

OLIVER DICKINSON

Department of Classics and Ancient History, University of Durham

PAUL HALSTEAD

Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield

JOHANNES HAUBOLD

Department of Classics and Ancient History, University of Durham

SUSANNE HOFSTRA

Minneapolis, MN

KATHLEEN M. LYNCH

Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati

ALEXANDER MAZARAKIS AINIAN

Department of History, Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Thessaly

DIAMANTIS PANAGIOTOPOULOS

Institut fr Klassische Archologie, Ruprecht-Karls-Universitt Heidelberg

SUSAN SHERRATT

Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield

ANTHONY SNODGRASS

Clare College, Cambridge

Introduction

Susan Sherratt and John Bennet

The relationship between the Homeric epics and archaeology has suffered mixed fortunes over the course of the last century and a half, swinging between fundamentalist attempts to use archaeology in order to demonstrate the essential historicity of the epics and their background at one extreme, and outright rejection of the idea that archaeology is capable of contributing anything at all to our understanding and appreciation of the epics at the other. Although narrow questions of historicity, particularly in relation to the Homeric Trojan War theme, have been revived in recent years (see especially Latacz 2004), we have chosen in this volume to concentrate rather on exploring a variety of other, perhaps sometimes more oblique, ways in which we can use archaeology, and also philology, anthropology and social history, to help offer insights into the epics, the contexts of their possibly prolonged creation (cf. Snodgrass, ).

We have thus, on the whole, attempted to move beyond the old dichotomies between historicity and irrelevance and to bring a multi-disciplinary approach to the Homeric epics (and in some cases other epics both ancient and more modern see the contributions by Dalley, Beissinger and Beaton, ) by exploring not only their varied relationships to the archaeological record and the practice of archaeology, but also a variety of other issues, either explicitly or implicitly. These include such diverse questions as the relationships between visual and verbal imagery and the role of both of these in reflecting or enhancing elements of social and political ideology, the social contexts of epic (or sub-epic) creation or re-creation, the roles of bards and their relationships to different types of patrons and audiences, the ability of story-patterns, ideological elements and linguistic formulae to cross linguistic and/or cultural boundaries in general (and Near Eastern contributions to Homeric epic in particular), the construction and uses of history as traceable through both epic and archaeology, the nature of historical memory and its manipulation, linguistic and material-cultural stratigraphy as detectable in epic, composition-in-performance of oral history and its transmission and transformation, the relationship between prehistoric (oral) and historical (recorded in writing) periods, and the history of Homeric archaeology and other epic archaeologies in general. Throughout, our emphasis is above all on context and its relevance to the creation, transmission, re-creation and manipulation of epic in the present (or near-present) as well as in the ancient Greek past.

The Dating of Homers Epics: Late 8th Century BC and Later

For long it was received wisdom among Classical scholars that the Homeric epics, whatever their earlier prehistory (see below), were created, or at least emerged or crystallised in a more or less recognisable form, sometime around 700 BC, give or take a few decades on either side. This was despite the knowledge that the texts, as we know them, were divided into books and heavily edited by Alexandrian scholars. In recent decades, however, this view has been challenged - for example, by Minna Jensen (1980), who argued that the epics did not take on any recognisable form until they were written down in Athens in the Peisistratid period of the later sixth century BC, and by Gregory Nagy (e.g. 1995; 1996: 2964), who sees the epics, as John Myres (1930) saw the Greeks themselves, as ever in the process of becoming through several distinct stages of formation, from the Bronze Age right down to the Hellenistic period. The question of writing is often brought into this debate. There are some who believe that writing was essential for the crystallisation of the epics, and that, if they were products of the late eighth century, they must have been written down at the first opportunity. Indeed, Barry Powell (1991) has argued that the Greek alphabet was adopted and adapted specifically to write down the Homeric epics in the later 8th century. Others (e.g. Kirk [1962]), by contrast, believe that it is not impossible to conceive of the epics being transmitted orally in comparatively stable form by rhapsodes for a couple of centuries before being committed to writing. In this volume, Snodgrass (Homer, the moving target, ) argues that nothing recognisable as definitively Homeric is likely to have emerged by the end of the eighth century, even if cycles of epic poetry, including some story-patterns of the sort familiar from the Homeric epics, were already in circulation. Fully accepting Nagys long-term evolutionary model for the epics and its implications of a long period of fluidity of creation and re-creation, at least before commitment to writing in the sixth century BC, he suggests that looking for chronological correlates in the archaeological record for particular passages is the equivalent of shooting at a moving target over a very long run, in which widely separated chronological circumstances may have produced similar archaeological effects, particularly since many Homeric descriptions can in effect be interpreted in a variety of different ways. Nevertheless, the target (or rather, perhaps, a whole series of different targets) is an important one, and for individual passages or elements of these we should not give up the search to find some context or contexts that might explain what gave rise to these and their inclusion. This, in Snodgrasss words, may turn out to be a much more stimulating sport than tackling the stationary target of an assumed late eighth century Homer.

Next page