A Homeric Catalogue of Shapes

Imagines Classical Receptions in the Visual and Performing Arts

Series Editors: Filippo Carl-Uhink and Martin Lindner

Other titles in this series

Art Nouveau and the Classical Tradition,

Richard Warren

The Ancient Mediterranean Sea in Modern Visual and Performing Arts,

edited by Rosario Rovira Guardiola

Classical Antiquity in Heavy Metal Music,

edited by K. F. B. Fletcher and Osman Umurhan

For RvS who loves books and

TvS who is always making things.

Contents

All photographs Courtesy Isabelle Grobler, all illustrations (Figs 25) by the author.

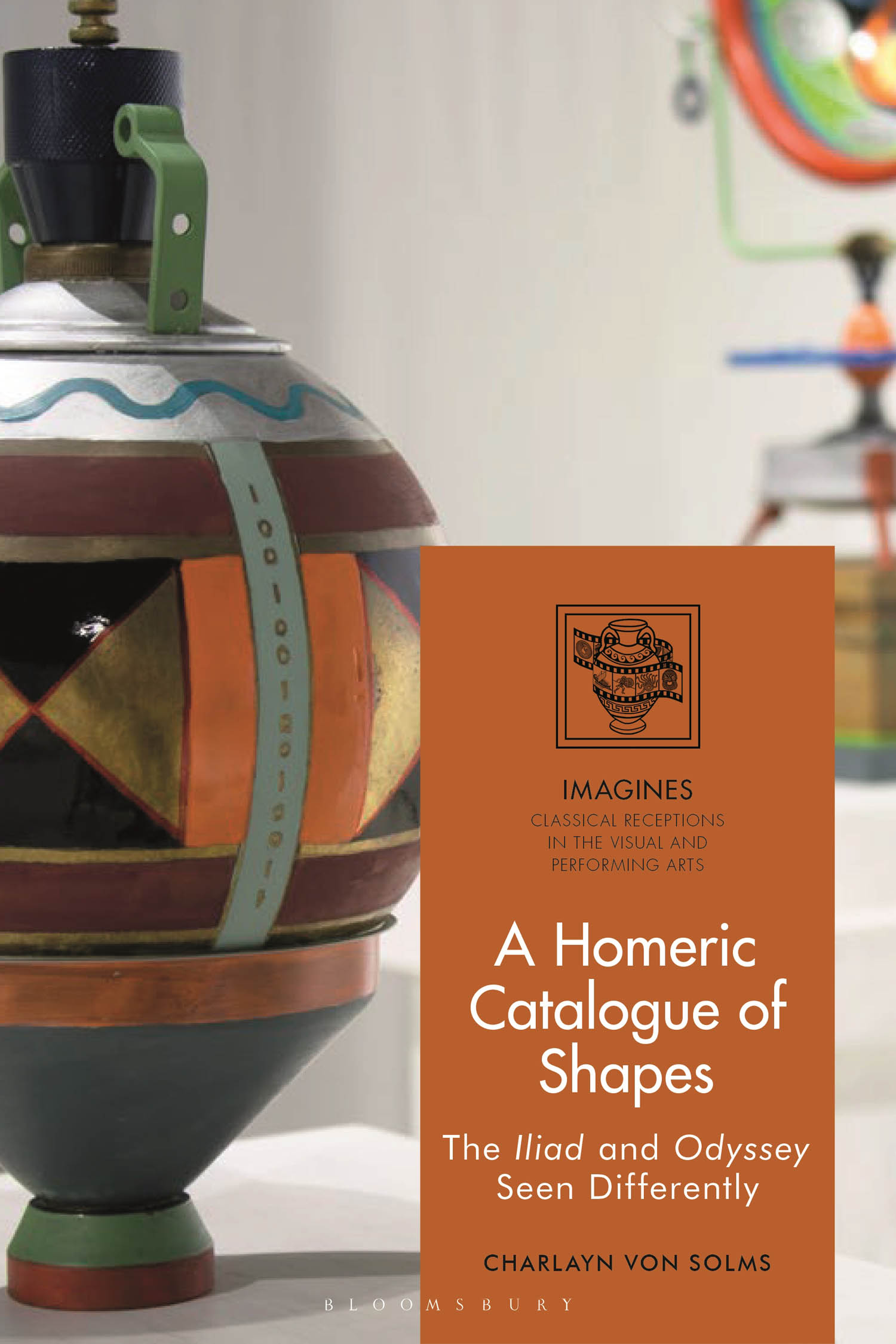

Detail of KALYPSO , 2012

Schematic representation of the spatial arrangement of A Catalogue of Shapes

Schematic representation of the primary interrelations between the sculptures comprising A Catalogue of Shapes

Upper and lower compositional registers in A Catalogue of Shapes

Preliminary drawing of TELEMACHOS, , 2011

Installation view of A Catalogue of Shapes

Front view of ODYSSEUS , 2010

Side view of ODYSSEUS , 2010

Back view of ODYSSEUS , 2010

Front view of ACHILLEUS , 2011

Side view of ACHILLEUS , 2011

Back view of ACHILLEUS , 2011

Front view of TELEMACHOS , 2011

Side view of TELEMACHOS , 2011

Back view of TELEMACHOS , 2011

Front view of HEKTOR , 2011

Side view of HEKTOR , 2011

Back view of HEKTOR , 2011

Front view of PENELOPE , 2011

Side view of PENELOPE , 2011

Back view of PENELOPE , 2011

Front view of HELENA , 201112

Side view of HELENA , 201112

Back view of HELENA , 201112

Front view of KALYPSO , 2012

Side view of KALYPSO , 2012

Back view of KALYPSO , 2012

Front view of ERIS , 2012

Side view of ERIS , 2012

Back view of ERIS , 2012

Front view of KIRKE , 2012

Side view of KIRKE , 2012

Back view of KIRKE , 2012

Front view of ATE , 201213

Side view of ATE , 201213

Back view of ATE , 201213

Front view of NESTOR , 2013

Side view of NESTOR , 2013

Back view of NESTOR , 2013

Front view of MENELAOS , 2013

Side view of MENELAOS , 2013

Back view of MENELAOS , 2013

In sculptural terms, I am a constructivist. I build an artwork from various separate parts derived from various objects, scraps and materials. When making a sculpture my focus is on constructing meaning by employing the expressive capacity of seemingly incompatible (and often banal) things to create a completely new entity: what the addition of each element means to the whole and how it alters and is altered by the others. But alongside this conceptual process, there is a practical one: working out how to connect objects and materials comprising different weights, densities, surface textures, tensile qualities, etc. to one another. Ensuring that irrespective of how tenuous or fragile I want an element, a link or a balancing act to appear to the viewer, it is provided with an underlying structure strong enough to withstand years of future transit and handling. The more effortless the final set of connections should be, the greater the engineering required. These processes the conceptual and the technical are wholly intertwined. The one informs the other and they are both essential, and equally enjoyable, aspects of making sculpture.

A comparable awareness of the interplay between methodology and meaning occurs in Homeric studies in the notion of an oral-formulaic Homer. My first encounter with this idea came via Gregory Nagys Greek Mythology and Poetics, which I stumbled across in 1997 (while trying to figure out what the notion of the Muse signified in Homer and Hesiod). As compelling as the description of ancient poets working within a tradition of constructing contextually-determined poems from pre-existing formulae, characters and plot-lines, was the nature of the scholarship itself. Homeric theory is innovative, well-crafted and stylistically diverse. The work of scholars such as Egbert Bakker, Leonard Muellner and Ahuvia Kahane (to name but a few) is premised on close and meticulous analysis of the fabric of the poems. Small, seemingly innocuous details are scrutinized within the context of the line in which it occurs, then the passage, the book and finally the entire poem, to produce radical insights, such as the multiple and contextually-defined meanings of one word (see Muellners The Meaning of Homeric EUCHOMAI Through its Formulas). There is an emphasis on describing the underlying structure that makes the epics both sturdy, yet sufficiently flexible, to survive for millennia. This is interpretation based on an insistence on seeing the Iliad and the Odyssey in a completely different way.

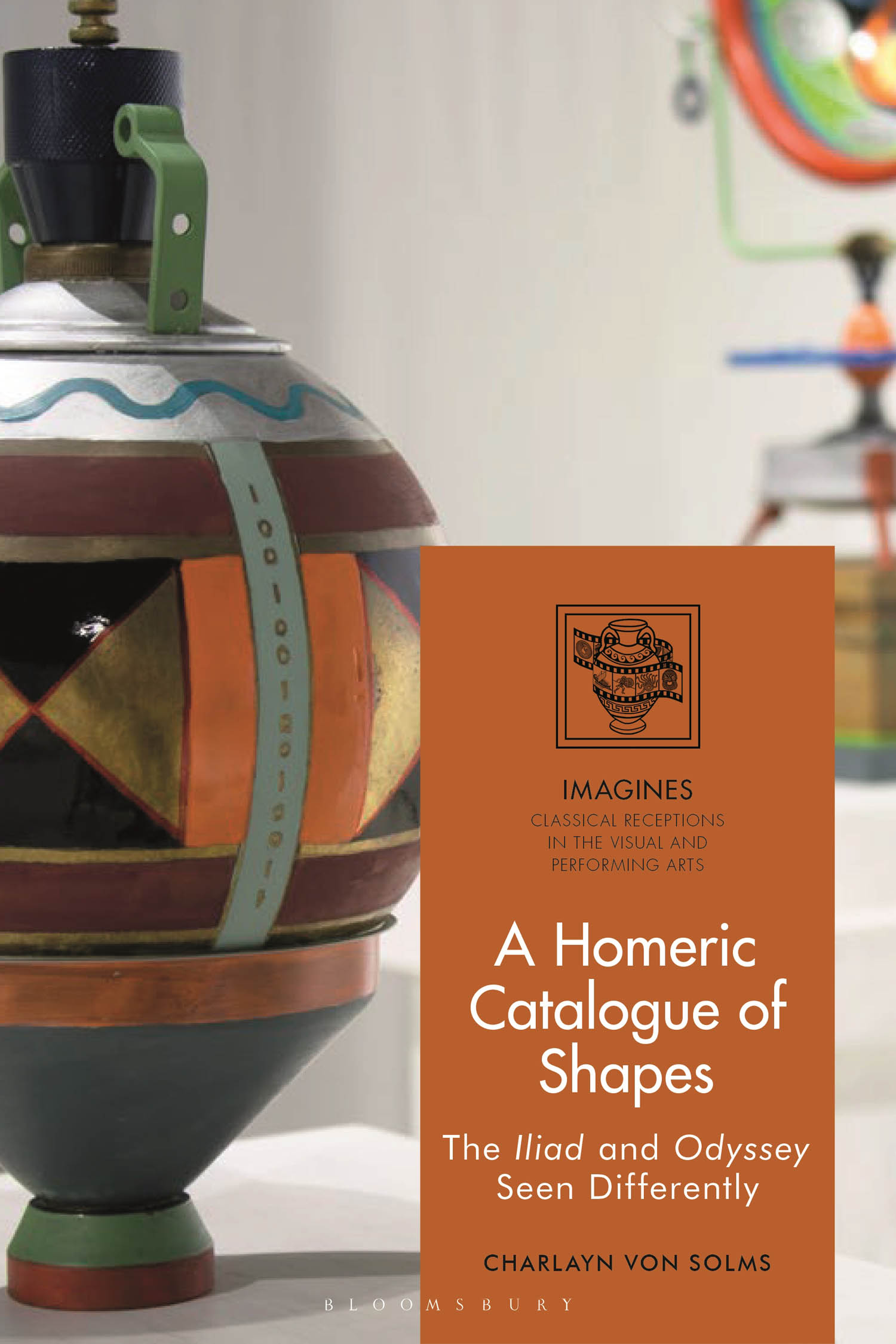

The sculptural project described in this book was inspired not just by the idea of Homer as described by these scholars, but also the nature of the scholarship itself. In my opinion, both these constructs deserve a much larger audience: they must be seen, and my expertise lies in showing. This book charts the thinking that underpinned the making of A Catalogue of Shapes. As such, it does not provide a comprehensive overview of the theory of an oral-formulaic Homer, but the ideas I most respond to. At its core, the book describes both methodology and interpretation. I hope that I have managed to achieve a balance between these, but there are areas where I have admittedly indulged in technical details.

As this publications forms part of an academic series, the budget could not stretch to colour images. Colour is however, an important signifying feature of the sculptures that comprise A Catalogue of Shapes. Fortunately, this is a digital age, and colour versions can be found in cyberspace. The ideal way to view them though, is to walk amongst the sculptures themselves (schematics showing the arrangement of the works appear in Chapter 4). My aim was to create a physical environment where the viewer, like a rhapsode, composes the epics by finding allusions, similes and visual puns; establishing points of correlation and disjunction; and tracing the various interrelationships between characters and plot-points. Here the slow process of circumvention, searching, discovering, and making connections serve as metaphor for creative and interpretive construction.

I thank Professors Clive Chandler and Bruce Murray Arnott for their enthusiasm, guidance and willingness to brave parts unknown; the members of the Western Cape chapter of the Classical Association of South Africa for their warm reception; and Isabelle Grobler for the photographs and her company on all those trips to Milnerton flea-market. I gratefully acknowledge the generous financial assistance of The South African National Research Foundation and the University of Cape Town Scholarships Committee.

The series of twelve sculptures entitled A Catalogue of Shapes resulted from an exploration of an equivalence between two seemingly disparate art-forms Homeric poetry (the Iliad and the Odyssey) and sculptural assemblage. While sculptural assemblage is a visual, and largely abstract, art-form, the Homeric epics are literary works that developed from oral traditions to encompass vivid narratives, characterization, similes and metaphors. Superficially, these two forms of expression seem antithetical to one another. However, comparisons of compositional methods reveal surprising similarities. Sculptural assemblage developed from two-dimensional

Next page