BOLLINGEN SERIES XLI

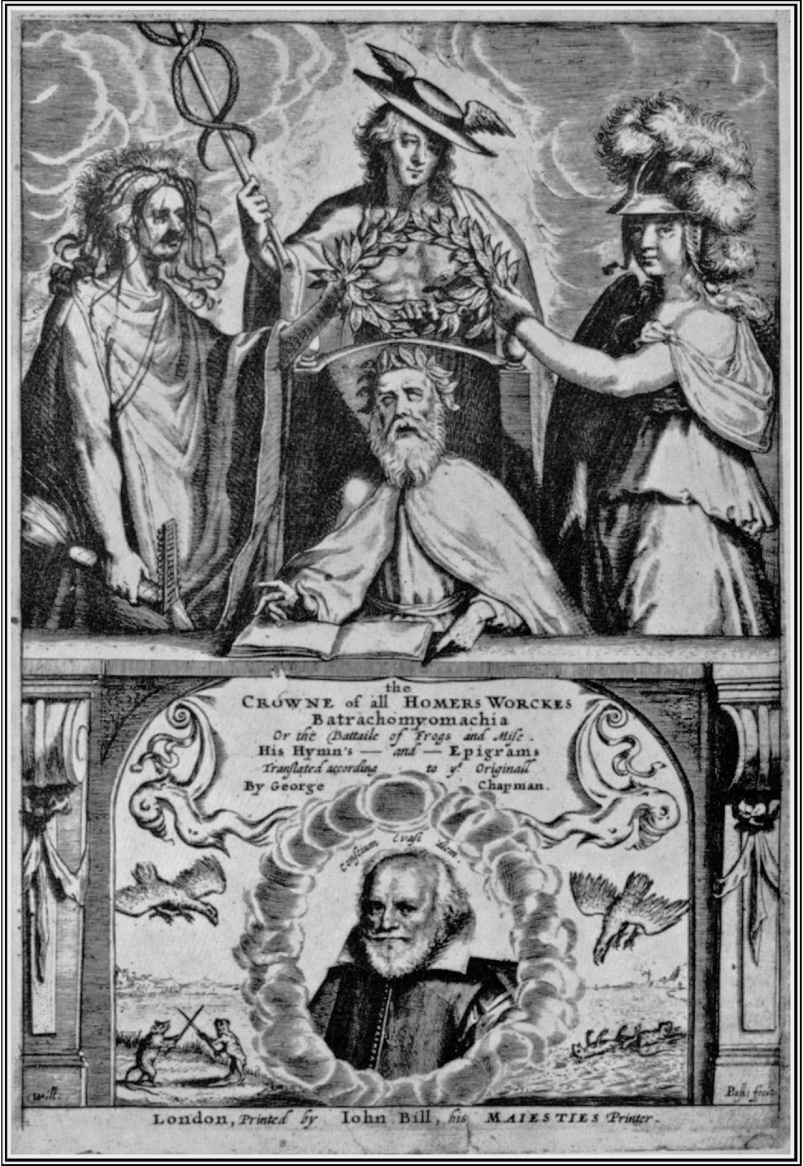

CHAPMANS

HOMERIC HYMNS

AND OTHER HOMERICA

Edited by

ALLARDYCE NICOLL

With a New Introduction by STEPHEN SCULLY

BOLLINGEN SERIES XLI

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2008 by Princeton University Press Copyright 1956 by Bollingen Foundation, Inc., New York, NY

Copyright renewed 1984 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

First paperback printing 2008

THE ORIGINAL EDITION, TITLED,

CHAPMANS HOMER: THE ILIAD, THE ODYSSEY AND THE LESSER HOMERICA, WAS THE FORTY-FIRST IN A SERIES OF WORKS SPONSORED BY AND PUBLISHED FOR BOLLINGEN FOUNDATION

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Homeric hymns. English

Chapmans Homeric hymns and other Homerica / edited by Allardyce Nicoll ; with a new introduction by Stephen Scully.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-691-13675-2 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-691-13676-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Hymns, Greek (Classical)Translations into English. 2. Gods, GreekPoetry. I. Homer. II. Chapman, George, 1559?1634. III. Nicoll, Allardyce, 18941976. IV. Scully, Stephen, 1947 V. Title.

PA4025.H8C48 2008

883'.0108dc22 2008002024

press.princeton.edu

eISBN: 978-0-691-22753-5

R0

CONTENTS

by Stephen Scully 1

THE HOMERIC HYMNS AND GEORGE CHAPMANS TRANSLATION

Stephen Scully

George Chapmans Renaissance translation of the Homeric Hymns is its first rendering into English. Chapmans efforts stride with robust Shakespearean vigor and are a source of delight even for modern readers, both as poems in our tongue and as lovely stories of the Greek gods. The Hymns are a collection of thirty-three poems celebrating the gods and goddesses of the Greek Pantheon from Mother Earth, the Sun, and Moon to Zeus, his children, and his childrens children. Though gathered under Homers name, they are anonymous compositions, varying in length and excellence, the best having the concentration and splendor of Homers own achievements. Like all Greek narrative poems, they are composed to entertain and enthrall even as they also reveal and honor a deitys deeds and powers. The many modern translations of these hymns testify to the pleasure they continue to bring both to students of Greek literature and to the general reader.

The Hymns, like the poems of Homer and Hesiod, are epea: epic songs in dactylic hexameter in an artificial poetic dialect. The hybrid collection, consisting of five long poems followed by twenty-nine short ones, vary in length from six hundred lines to just three. Yet, even within such variation, most of the poems exhibit a common form: (1) a formulaic opening identifies the god invoked and draws attention to the poem itself as a beginning; (2) the middle describes the gods birth or a telling attributein brief or at length; (3) a formulaic close bids farewell to the deity and again draws attention to the activity of singing as the composer indicates that he is about to move on to a new song. Often in this context the singer will ask the god to favor him over other poets in a competitive performance. To the best of our knowledge, the form is very old, invoking both a god and the performative nature of the song.

The date of the collection is uncertain. It appears to be late, compiled by scholars at the Library of Alexandria in the second century BCE. In all likelihood, the compilers were also the first to attribute the multiple hymns to Homer, although variations in diction, style, and geographical perspective indicate that most of the poems were composed at different times and places on the Asia Minor coast and the Greek mainland roughly between 675 and 450 BCE in the Archaic and Classical periods. The earliest extant references to the collection come from two very different authors in the first century BCE, the Epicurean teacher of philosophy Philodemus and the historian Diodorus Siculus, both of whom refer to Homer in the hymns. Even though shared dialect, meter, and certain elements of style, especially in the splendor of the long narratives, might serve to remind later audiences of Homer, there were certainly many in this period who questioned the Homeric authorship of these poems. Such may be inferred from the scant reference to the collection in antiquity, including the surprising absence of any allusion to the Hymns in the ancient commentaries to the Iliad or Odyssey. But if not to Homer, the source of the poems could reasonably have been attributed to the Homeridae (Sons of Homer), a clan or school of rhapsodes in the Archaic and Classical periods who claimed descent from Homer; or, even more appropriately, attributed to Hesiod, Homers contemporary, who in his Theogony and Catalogue of Women wrote about the gods, their births, attributes, and love affairs.

While the collection itself is late, the genre of these hymns almost certainly dates back to Homersand Hesiodstime. When quoting from what he calls the Hymn to Apollo (with no reference to Homer), Thucydides refers to the song as a prooimion, or prelude (3.104). Plato uses the same term to describe a song that Socrates composes to Apollo while waiting in prison to drink the hemlock (Phaedo 60d). Pindar refers to something of the sort as a prelude: Just as the Homeridae, singers of woven stories, very often began with a prooimion from Zeus, so this man... (Nemean 2.13). It was the custom in ancient recitations of long narrative epic about heroes, sometimes called an oim (literally, a path or poem), to begin with a short poem to a god, a pro-oim.

Even if the Homeric Hymns seem to have seen themselves as fulfilling that introductory function, they do not refer to themselves as prooimia. Rather, they call themselves songs (aoidai), and their composers singers (aoidoi) who sing (aeidein), also commonplace terms in Homer and Hesiod for epic singing. On rare occasions, the Homeric Hymns also identify themselves as hymns (humnoi), a term used rather vaguely once in Homer to refer to an after-dinner song and also found once in Hesiod. More pointed perhaps is the verb to hymn (humnein) [a song in praise of] a god, which is found in Hesiod and often in the Homeric Hymns but never in Homer. It is from the verb that the noun came to specify a song in celebration of a god or goddess.

Even the shortest of the Hymns, a three-liner to Demeter, manages to convey much of the genres formulaic structure:

Of Demeter, golden-haired, revered goddess, I begin to sing,

both her and her daughter, the exceedingly beautiful Persephone.

Hail and farewell, goddess, and save this city here, and begin my song.

(Homeric Hymn to Demeter #13)

The lovely six-line Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite

Next page