Introduction

A hymn is a song to a god, originally sung, usually to a lyre. The meaning of hymn is unclear and it may have a foreign origin. The word occurs only once in Homer ( Odyssey 8.429), and Hesiod speaks of winning a prize for a hymnos ( Works and Days 651), but it is unclear what he meant by hymnos . Early hymns seem to have been composed in hexameters (see below), but later poems appear in other meters. The standard form was to list the gods names, thus invoking his or her presence, then to continue with some event from the gods career, often the gods birth, and to conclude with a prayer, a reference to the god, or a declaration that the hymnist would now proceed to another song. Hymns to the gods must have been widely circulated in antiquity but, puzzlingly, they are not often referred to by other ancient writers.

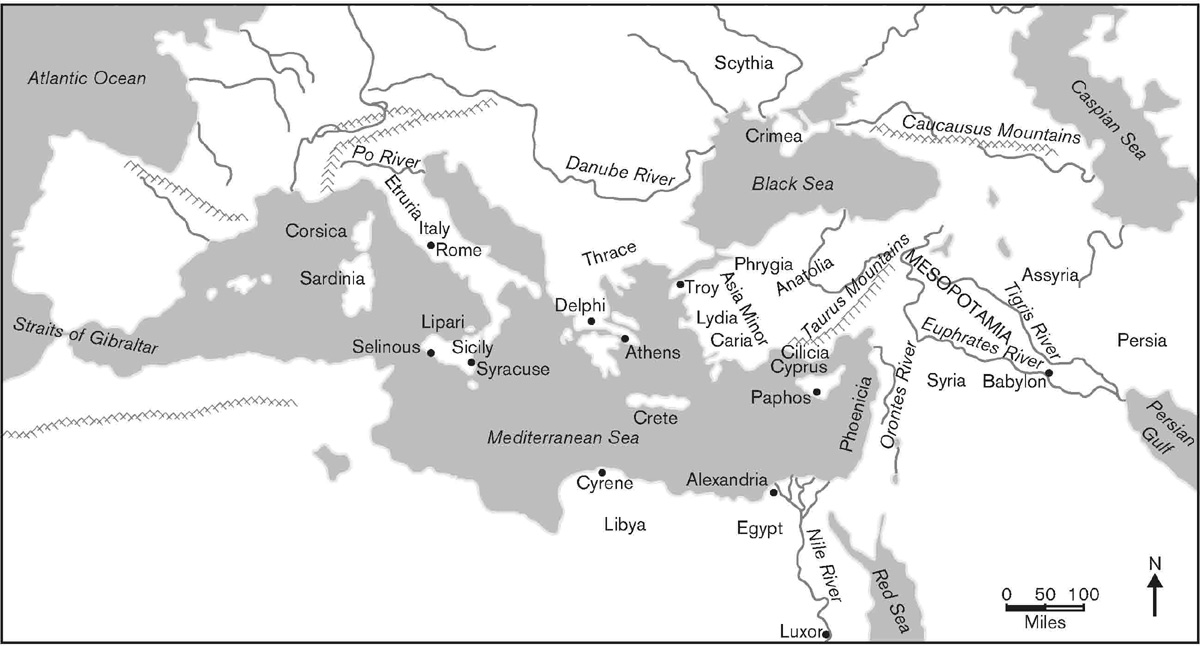

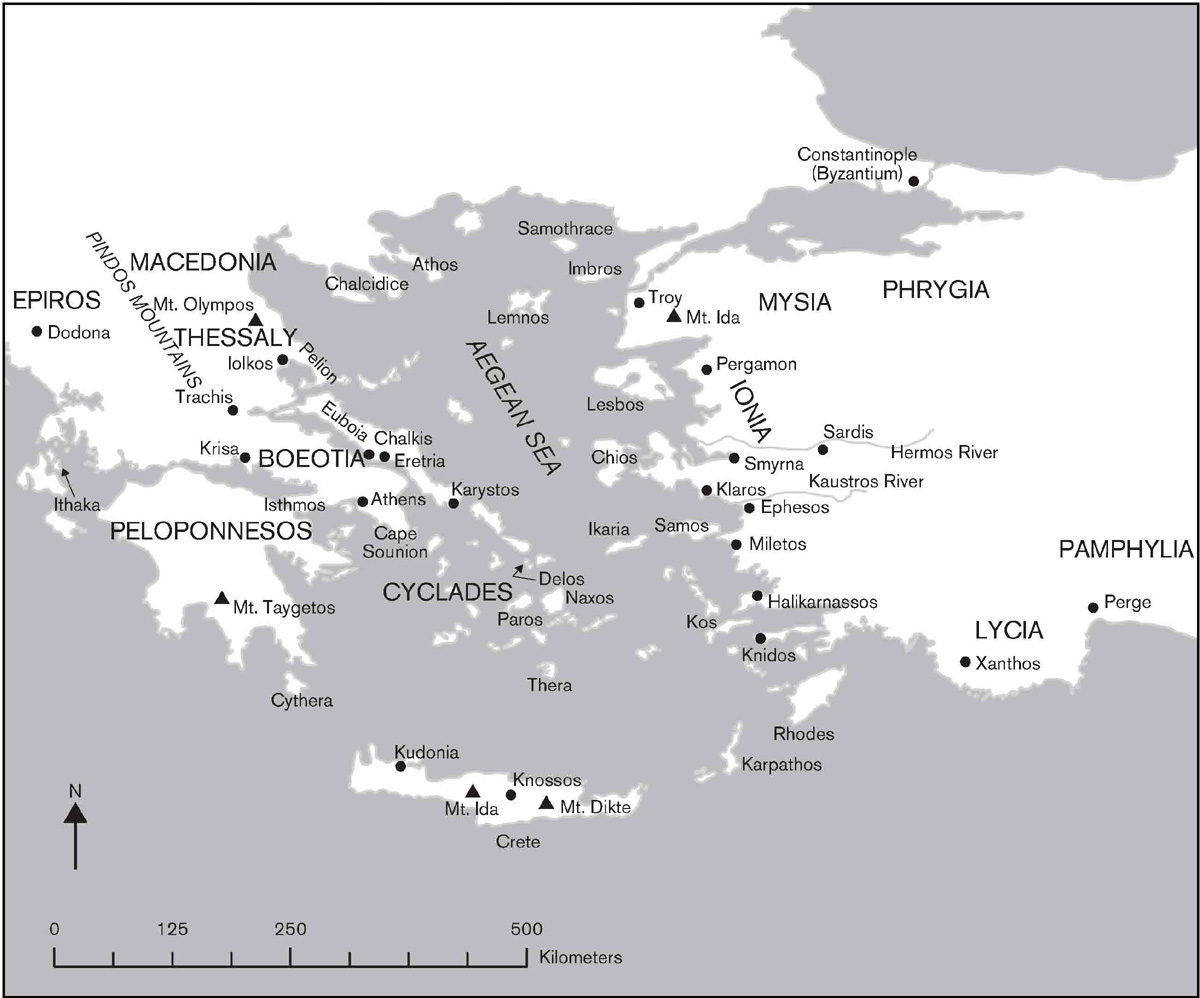

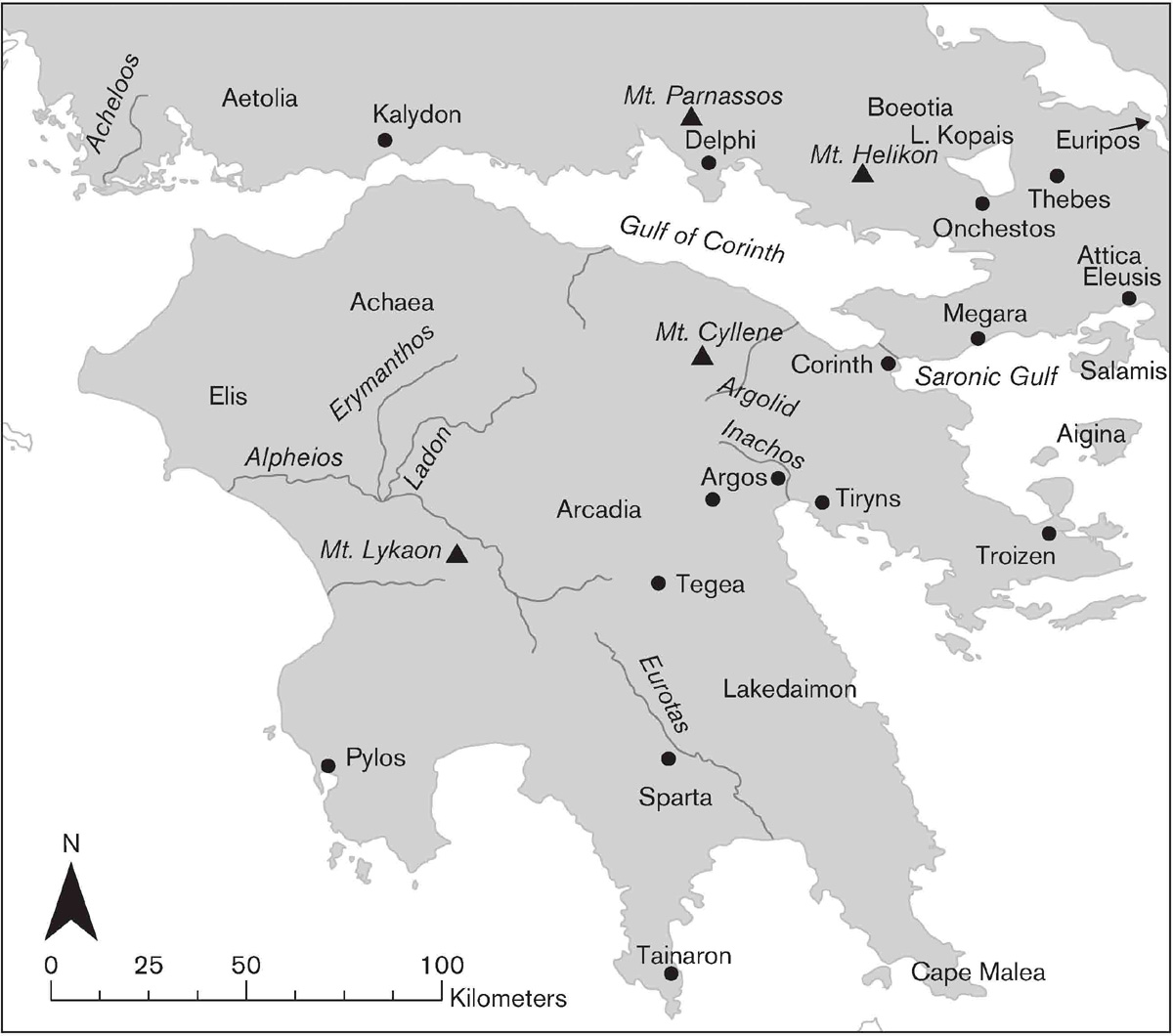

A remarkable collection of Greek hymns, by a range of authors, survives in twenty-nine manuscripts, none older than the fifteenth century AD. They are among our most important sources for our knowledge of Greek myth. The collection was evidently made in the early Middle Ages and included, in this order: the anonymous Orphic Hymns (c. AD second/third century?); the Hymns of Proclus, an important Neoplatonist philosopher of late antiquity (AD 412485); the anonymous Homeric Hymns (eighth/seventh centuries BCfifth century BC, with one exception), our earliest surviving hymns; and the Hymns of Callimachus (c. 310c. 240 BC), from the Hellenistic Age (323-c. 30 BC); Callimachus was a poet, critic, and scholar at the Library of ALEXANDRIA (see map 1; place-names that appear in the maps are in small caps), one of the most influential intellectuals of his day. The collection also includes an anonymous Orphic Argonautica from the fifth or sixth centuries AD that tells the story of Jason with an emphasis on the role of Orpheus, but it is not a hymn and is not translated here.

One of these manuscripts, discovered in Moscow in 1777 and now in Leiden, is unique in containing a portion of a Homeric Hymn to Dionysos and the long Homeric Hymn to Demeter, poems not included in other versions of the collection. Several papyrus fragments also preserve portions of the Homeric Hymns. The manuscripts of the collection are not nearly so well preserved as texts of the Iliad and the Odyssey and there are many corruptions, some incurable, and occasionally misplaced lines. The collection (missing only the hymns to Dionysos and Demeter) was printed in the editio princeps of Homers Iliad and Odyssey, published in Florence in 1488 by Demetrios Chalkokondyles, one of the most eminent Greek scholars working in the West, tutor to the sons of Lorenzo de Medici.

This book will contain translations of most of these hymns, arranged not as they are in the collection, but according to each individual deity. In this way the reader can see how Greek poets, during a period of over one thousand years, conceived and celebrated their gods, allowing the reader to form an impression of how notions of each god evolved over nearly a millennium. All the hymns of Callimachus and Proclus are included, together with twenty-eight of the thirty-four Homeric Hymns , and thirty-two of the seventy-eight Orphic Hymns ; hymns to minor gods, such as the Orphic Hymns to Justice, Mis, the Seasons, Leukothea, and the like, are omitted. The hymns will be cited in rough chronological order: first the Homeric Hymns; then the Hymns of Callimachus; then the Orphic Hymns; then the Hymns of Proclus.

METER AND PERFORMANCE

The hymns are mostly composed in a Greek meter that modern scholars call dactylic hexameter, the same meter used in the Iliad and the Odyssey. Each line consists of six feet, each of which may be a dactyl (a long and two shorts, , like the knuckles on a finger, hence the name, which means finger), or a spondee (two longs, ; the name means libation, being characteristic of poetry that accompanied libations). The last foot is always a spondee. Vergil (7019 BC) imitates this meter in his Latin Aeneid:

/ / / / /

Arma virumque cano, Troiae qui primus ab oris ...

I sing of arms and the man who first from the shores of Troy ...

as does, in English, Longfellow in his Evangeline (1847):

/ / / / /

This is the forest primeval, the murmuring pines and the hemlocks ...

This was the meter of Greek oral poets, really an unconscious rhythm. Rhyme is avoided. The oral poet was not conscious of any division of the line into its constituent feet, as indicated above. Such schematization is a result of modern analysis of written texts. Probably, however, the poet felt the line as a whole, as a unit. Early inscriptions, based on oral delivery, though very short, seem to divide the text into lines, though the words are run together.

The origin of this complex meter has been the subject of intense speculation because the natural rhythm of spoken Greek is iambic (). Some scholars have thought that dactylic hexameter was adopted from a foreign language; others describe it as a native formation. In fact its origin is not known, but it was already old in antiquity and the oral poet learned it by apprenticeship to a master of the tradition. Dactylic hexameter does not work well in English, and I abandon it entirely in this translation, preferring a rough five-beat iambic line that accurately preserves the meaning of the Greek.

Because the oral poet, always a male entertainer as far as we know, composed in this meter on the fly and at a rapid pace he made use of such formulas as flashing-eyed Athena or Artemis of the golden shafts or the wine-dark sea. Such preset phrases filled out his line so that he did not have to recreate appropriate metrical locutions every time from scratch. They also provide, in the case of epithets attached to names, a capsule summary of the qualities of the god, person, or thing. We might think of this oral poetry as composed in a special language in which, to a remarkable extent, phrases, rather than words, were the units of expression. Such was the nature of dactylic hexameter in the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Homeric Hymns. The later, written poetry of Callimachus, the Orphic Hymns, and Proclus imitated this rhythm, although it had lost its function as an aid to oral performance. So great was the prestige of the Homeric poems.