BETWEEN

EAST AND WEST

T HE O RIGINS OF M ODERN R USSIA : 8621953

R. D. CHARQUES

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK LONDON

CHAPTER I

THE EURASIAN

BACKGROUND AND THE SLAVS

A N AREA OF NINE million square miles, almost a sixth of the earths land surface, and a population of appreciably more than two hundred million of whom three-quarters are Slav but who comprise some sixty different nationalities and more than twice as many ethnic groups of smaller size: such was the mighty Union of Soviet Socialist Republics at its apex. How did it come into being?

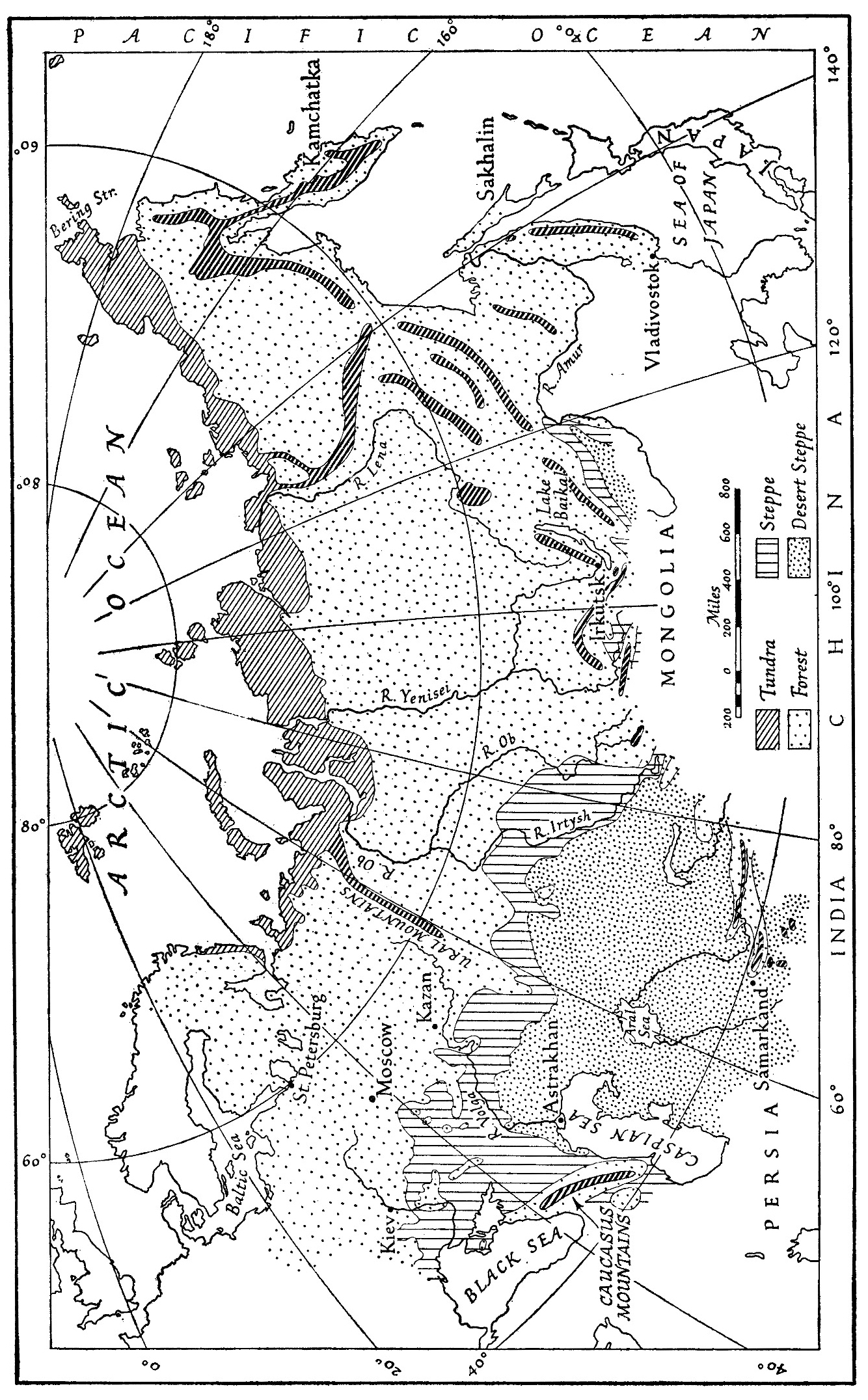

Look at the map. Geography, which moulds the life of nations, has been a constant determinant of Russian history. In one sense, it still is.

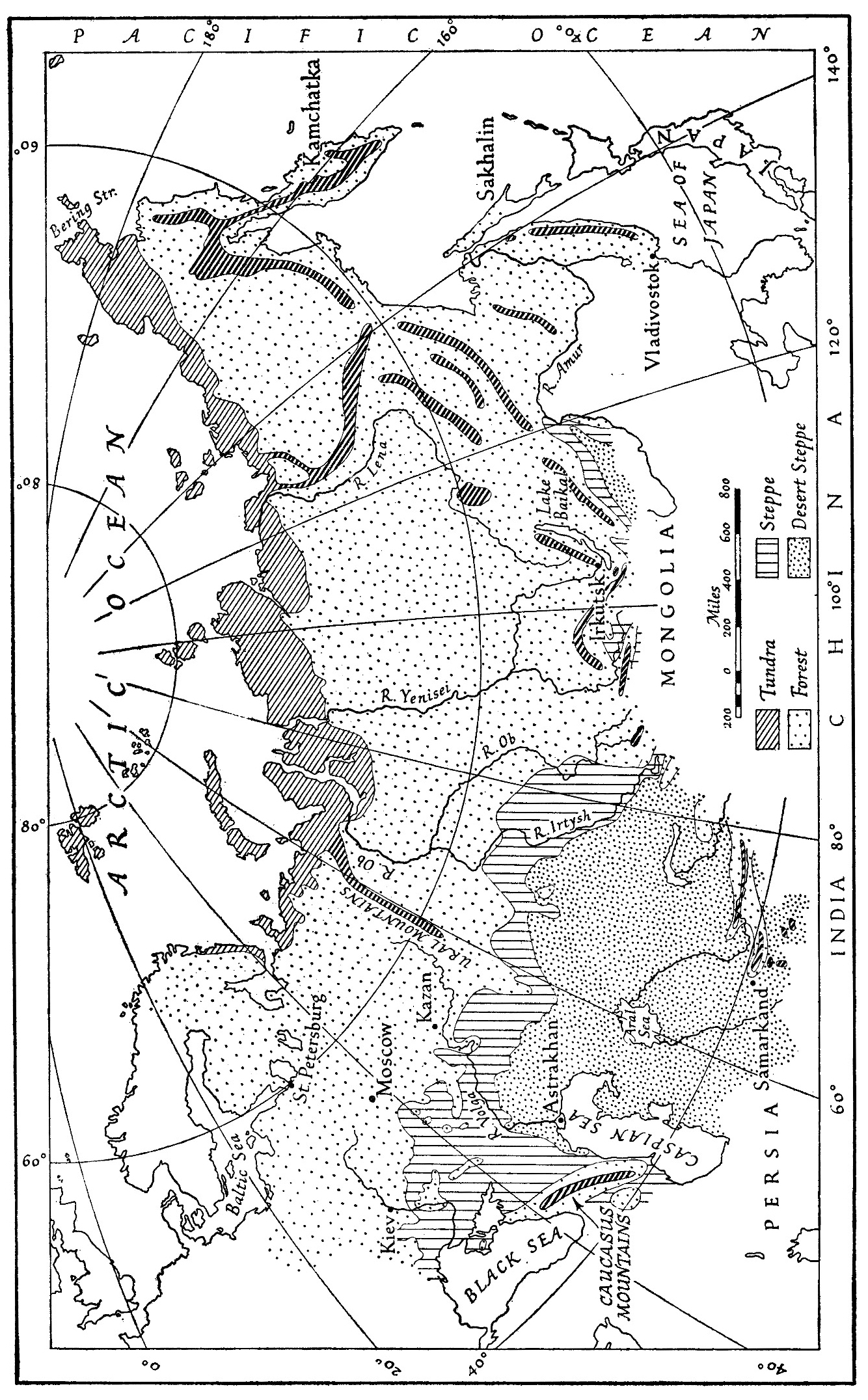

Look at the three basic maps of the physical geography of Russia: the continuous, all but illimitable plain, or series of adjoining plains, the distribution of soil and vegetation, the rivers of western Russia. On these maps are written the commonplaces of eleven centuries of the historical development of the Russian state.

First, the vast level land stretching from the Baltic and the Carpathians across Siberia to the Pacific. East and south on the far rim of the plain are high mountain ranges, but, except for the narrow chain of the Urals running across it from north to south, within all that immensity of space the land is scarcely anywhere more than a few hundred feet above sea level. This is the unbroken mass of Russia in Europe and Russia in Asia. The Ural Mountains, which in the atlas still serve to divide Europe from Asia, are in no sense a natural barrier, since from gradual foothills they rise to a mean altitude of no more than 1,500 feet. Nor, apart from greater extremes of winter cold and storm in the east, does the atlas division mark any natural difference. On either side of the Urals the distinguishing features of soil and vegetation are identical. And through the wide southern passage between the Urals and the Caspian Sea, in historical and pre-historical witness to the geographical unity of the plain, the waves of migration from Asia have flowed westwards across those treeless expanses known as the steppes, their distant horizon evoking in other than landlocked eyes an irresistible image of the expanses of the ocean.

From this absence of any significant natural barrier to stem the tide of internal migration springs the motive force of the Russian past. The history of the Russian people derives in the first place from a continuous and still uncompleted process of colonization. Wanderers in vast and all but empty lands, they extended the boundaries of settlement with what can only be called the sanction of geography. It is this sanction which makes them wanderers still. Where other nations expanded oversea the Russian empire grew by migration into endlessly contiguous territories. The price of empire-building on so vast a scale was eventually paid in the maintenance of autocracy and serfdomin the ultimate reckoning, in the Russian revolutionbut in historical retrospect the whole evolutionary process wears a simple and fateful logic.

Not unlike the United States, Russia has evolved, through still wider spaces and over a larger stretch of time, from an advancing frontier. Northward to the Arctic Circle and beyond to the ice of the ocean, reaching in the easternmost corner the tongue of land separated by only seventy miles of the Bering straits from the American continent; southward to the Black Sea and the Caspian and the Caucasus between; eastward to the Sea of Japan and the border regions of China and India, the frontiers were pushed forward almost entirely by settlement and only in the last resort secured by war. In the west alone, where expansion met the eastward drive of other peoples, was the frontier for so long unsettleda condition reflecting the age-long problem of the cultural boundary between Russia and Europe.

Next, across the whole of the Eurasian land mass, there is the regular latitudinal succession of distinctive zones of vegetation: tundra, forest, fertile steppe, desert steppe. The zones expand or shrink in depth between the eastern and western extremities and often overlap. In the west, below the forest region which presents to the foreign travellers eyes the characteristic Russian landscape of pine, fir and birch, the central deciduous forest meets arable steppe in a wide belt of wooded open country which is the vital scene of political growth in Russian history; in the east, the desolation of the tundra merges into the impenetrable northern stretches of the Siberian taiga. But over the whole land the same succession of vegetation zones prevails, with the great stretch of chernozem, the famous black earth, at the agricultural heart of the steppe. This natural scheme has dominated the course of internal Russian development through the centuries.

From the monotony of the infinite plain and its severities of climate came the endurance of the Russian people. And more than all else from the short season between seed-time and harvest came economic backwardness.

The tundra of the northern zone is vast and all but empty still. A wilderness of frozen marsh, over which move the reindeer herds, it has played little part in the march of Russian civilization. Soviet development in the Arctic for strategic ends, however, appears to have brought with it here and there dramatic hints of a transformed scene.

Vegetation Zones of Russia

The zone of arid steppe in the east and south-east, equally vast, includes the regions of many ancient cultures of central Asia, destroyed by barbarian war and conquest. Here modern technique has most sharply modified the old complex of geographical factors. Soviet development in these salt wastes, following on tsarist attempts to sow the desert, seems to prefigure a process of radical transformation. In the swift rise of industry, the growth of communications and the promise of ambitious works of irrigation the present appears to be joining hands with the remote past. For it was from these plains that the pastoral culture of the nomads reached across the fertile steppe to the agricultural settlements and commercial centres at the forest edge of the nascent Russian state, leaving in their passage to and fro enduring marks upon the whole order of Russian society.

Forest and steppe; steppe and forest. It is the shifting of the seat of power between them which points the logic of Russian political development. The original line of demarcation, which in the west reached from Kiev to just south of Moscow and thence to Kazan, near the junction of the Volga with the Kama, has long been obliterated in the creation of a single tract of agriculture. But it represents the axis upon which internal growth revolved. For long centuries forest and steppe constantly collided in war and as constantly met in commerce. They contributed twin and mutually conflicting impulses to the evolution of a migrant society. The Russia of the forest lived in constant peril from the Russia of the steppe, and the political institutions originating in the one were shaped by struggle with the menace from the other. Yet at the same time it was out of the exchanges between them that, first, Kievan Rus, the earliest but abortive Russian state, and then Muscovy, its successor, proceeded to develop a social habit and tradition of their own. In the formative phases of the unification of the east Slavs the nomads alone served as a link between the widely separated centres of an embryonic Russian civilization.