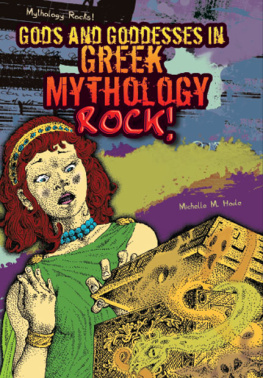

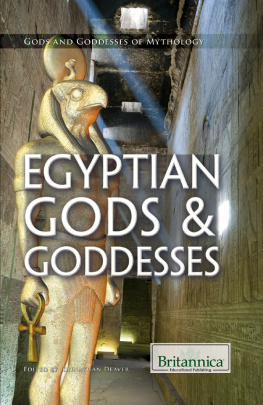

Published in 2015 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2015 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2015 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to http://www.rosenpublishing.com

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J. E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

Trenton Campbell: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Michael Moy: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Karen Huang: Photo Research

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Campbell, Trenton.

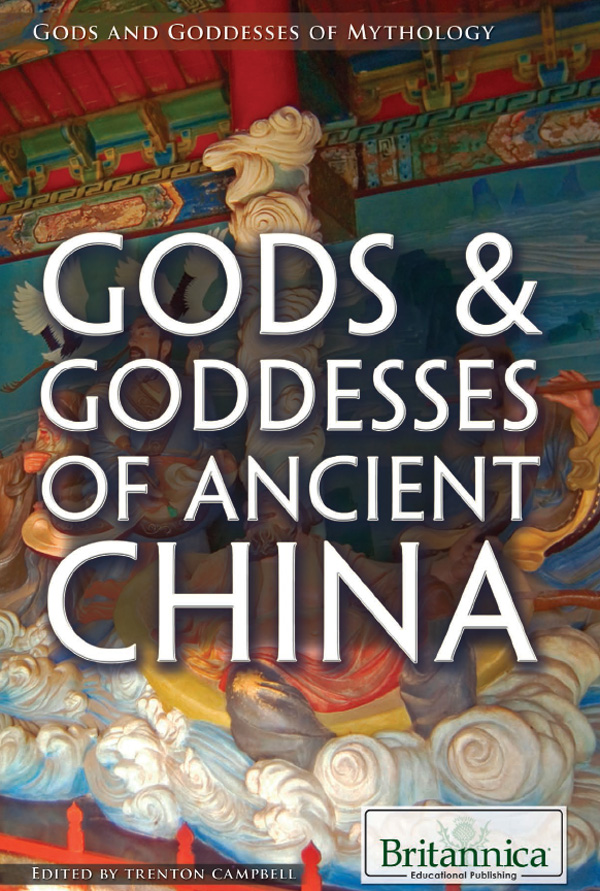

Gods & goddesses of ancient China/edited by Trenton Campbell.

pages cm. (Gods and goddesses of mythology)

Includes bibliographic references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62275-394-9 (eBook)

1. Gods, Chinese. 2. Goddesses, Chinese. 3. Mythology, Chinese Juvenile literature. I. Title.

BL1812.G63 C36 2015

299d23

On the cover: The Baxian are depicted in sculpture in the Eight Immortals Temple, Penglai City, Shandong province, China. One of the Eight Immortals has been cropped at the far left so that only seven are seen in this photograph. TAO Images Limited/Getty Images

Interior pages graphic iStockphoto.com/koey

CONTENTS

A wall sculpture of the legendary poet and statesman Qu Yuan in Beijings Millennium Monument Museum, which was built to commemorate the new millennium 2000 CE. Christian Kober/AWL Images/Getty Images

C hina is one of the great centres of world religious thought and practices. It is known especially as the birthplace of the religio-philosophical schools of Confucianism and Daoism (Taoism), belief systems that formed the basis of Chinese society and governance for centuries. Buddhism came to China perhaps as early as the 3rd century BCE and was a recognized presence there by the 1st century CE. The country became an incubator for many of the great present-day Buddhist sects, including Zen (Chan) and Pure Land, and, by its extension into Tibet, the source of Tibetan Buddhism. In addition, hundreds of animist, folk, and syncretic religious practices developed in China, including the movement that spawned the Taiping Rebellion of the mid-19th century.

Early Chinese literature does not present, as the literatures of certain other world cultures do, great epics embodying mythological lore. What information exists is sketchy and fragmentary and provides no clear evidence that an organic mythology ever existed; if it did, all traces have been lost. Attempts by scholars, Eastern and Western alike, to reconstruct the mythology of antiquity have consequently not advanced beyond probable theses. Shang dynasty material is limited. Zhou dynasty (c. 1046256 BCE) sources are more plentiful, but even these must at times be supplemented by writings of the Han period (206 BCE220 CE), which, however, must be read with great caution. This is the case because Han scholars reworked the ancient texts to such an extent that no one is quite sure, aside from evident forgeries, how much was deliberately reinterpreted and how much was changed in good faith in an attempt to clarify ambiguities or reconcile contradictions.

The early state of Chinese mythology was also molded by the religious situation that prevailed in China at least since the Zhou conquest (c. 11th century BCE), when religious observance connected with the cult of the dominant deities was proclaimed a royal prerogative. Because of his temporal position, the king alone was considered qualified to offer sacrifice and pray to these deities. Shangdi (Supreme Ruler), for example, one of the prime dispensers of change and fate, was inaccessible to persons of lower rank. The princes, the aristocracy, and the commoners were thus compelled, in descending order, to worship lesser gods and ancestors. Though this situation was greatly modified about the time of Confucius in the early part of the 5th century BCE, institutional inertia and a trend toward rationalism precluded the revival of a mythological world. Confucius prayed to Heaven (Tian) and was concerned about the great sacrifices, but he and his school had little use for genuine myths.

Nevertheless, during the latter centuries of the Zhou, Chinese mythology began to undergo a profound transformation. The old gods, to a great extent already forgotten, were gradually supplanted by a multitude of new ones, some of whom were imported from India with Buddhism or gained popular acceptance as Daoism spread throughout the empire. In the process, many early myths were totally reinterpreted to the extent that some deities and mythological figures were rationalized into abstract concepts and others were euhemerized into historical figures. Above all, a hierarchical order, resembling in many ways the institutional order of the empire, was imposed upon the world of the supernatural. Many of the archaic myths were lost; others survived only as fragments, and, in effect, an entirely new mythological world was created.

These new gods generally had clearly defined functions and definite personal characteristics and became prominent in literature and the other arts. The myth of the battles between Huangdi (The Yellow Emperor) and Chiyou (The Wormy Transgressor), for example, became a part of Daoist lore and eventually provided models for chapters of two works of vernacular fiction, Shuihuzhuan (The Water Margin, also translated as All Men Are Brothers) and Xiyouji (1592; Journey to the West, also partially translated as Monkey). Other mythological figures such as Kuafu and the Xiwangmu subsequently provided motifs for numerous poems and stories.

Historical personages were also commonly taken into the pantheon, for Chinese popular imagination has been quick to endow the biography of a beloved hero with legendary and eventually mythological traits. Qu Yuan, the ill-fated minister of the state of Chu (771221 BCE), is the most notable example. Mythmaking consequently became a constant, living process in China. It was also true that historical heroes and would-be heroes arranged their biographies in a way that lent themselves to mythologizing.

Gods & Goddesses of Ancient China examines the two main faiths that developed before China had meaningful contact with the rest of the world, Confucianism and Daoism, neither of which were formed around monotheism. Rather, they incorporate the worship of polytheism, the belief in many diverse deities and mythological beings. When Buddhism became popular in China, aspects of it joined features of the other two faiths to form the major elements of Chinese ideology and, together with the beliefs in immortals and the worship of ancestors, they lead to a Chinese popular religion. These pages introduce many of the gods and goddesses that dominated the mythology, folk culture, and religious worship of the people of ancient China, roughly from the 3rd millennium to 221 BCE.