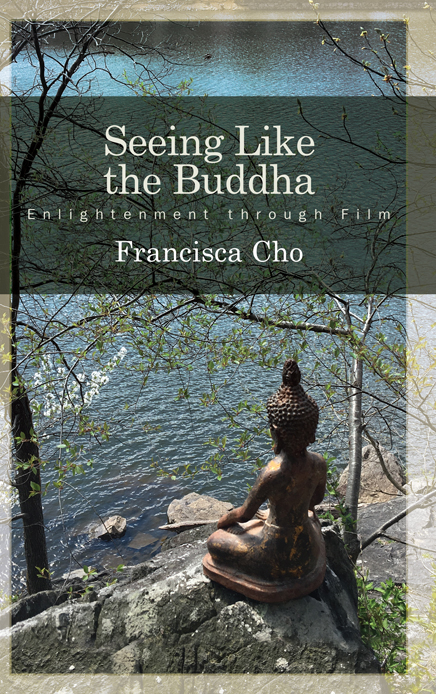

Seeing Like the Buddha

Seeing Like the Buddha

Enlightenment through Film

Francisca Cho

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2017 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Ryan Morris

Marketing, Kate R. Seburyamo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cho, Francisca, author.

Title: Seeing like the Buddha : enlightenment through film / Francisca Cho.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016031461 (print) | LCCN 2017001011 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438464398 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438464404 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Buddhism in motion pictures.

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.B795 C46 2017 (print) | LCC PN1995.9.B795 (ebook) | DDC 791.43/682943dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016031461

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgment

For the students of my Buddhism and Film course offered in the Spring semesters of 2010, 2012, and 2014: It has been a privilege to share my ideas with you and you have inspired me with your amazing insights in turn.

Abbreviations

| A | Anguttara Nikya. Translated by Bhikkhu Bodhi as The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2012. |

| AdS | Amityurdhyna Stra . Translated by Hisao Inagaki in collaboration with Harold Stewart as The Sutra on Contemplation of Amityus . In The Three Pure Land Sutras . Revised Second Edition. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation, 2003. |

| D | Digha Nikya . Translated by Maurice Walshe as The Long Discourses of the Buddha. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1995. |

| M | Majjhima Nikya . Translated by Bhikkhu amoli and Bhikkhu Bodhi as The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1995. |

| PraS | Pratyutpanna-Buddha-Samukhvasthita-Samdhi-Stra . Translated by Paul Harrison. Tokyo: The International Institute for Buddhist Studies, 1990. |

| S | Samyutta Nikya . Translated by Bhikkhu Bodhi as The Connected Discourses of the Buddha. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2000. |

| SN | Sutta Nipta . Translated by H. Saddhatissa. London: Curzon, 1985. |

| Vm | Visuddhimagga . Translated by Bhikkhu yamoli as The Path of Purification. Boulder and London: Shambhala, 1976. |

CHAPTER 1

Seeing Like the Buddha

Erasing the Buddha

T he objective of this book is to demonstrate that films can take on the role that has been played by traditional Buddhist icons and images. Film can articulate Buddhist teachings and, more significantly, put them into practice. This means taking film seriously as a medium for cultivating certain ways of being in the world that have previously been attained through ritual and contemplative practices. Both traditional and filmic practices can be put under the rubric of seeing like the Buddha, which is intimately tied to the desire of Buddhists to see the Buddha himself. As a founded religion, Buddhists express devotion and piety toward the historical Siddhrtha Gautama of the akya clan (kyamuni). This means keeping him alive through images and narratives about his life, similar to the way Jesus is kept in mind by Christians. And parallel to Christology, theoretical understandings about the nature of the Buddha as both a historical and transcendent being have allowed Buddhists to see him in multiple ways, as well as in multiple things. But throughout Buddhist history, the project of seeing the Buddha has entailed a mandate to see like the Buddha, which, paradoxically, erases the individual form of Siddhrtha. The emphasis shifts from what is seen to how one sees, which in turn renders art and aesthetic experiences into equivalents of the Buddha himself.

This drift toward erasing the Buddha in favor of seeing like the Buddha is the central aesthetic and soteriological theme of this book, and the organizational principle behind the films that have been selected for There are other kinds of Buddhist icons such as representations of bodhisattvas (Buddhas-to-be) and maala Buddhas that are endowed with fixed symbolic attributes. But there are also open form images that exhibit the layering and substitution of motifs (Shimizu 1992, 207). In such images, the Buddha is present primarily as a reference point that deliberately raises the question of what and whom else can be seen as the Buddha.

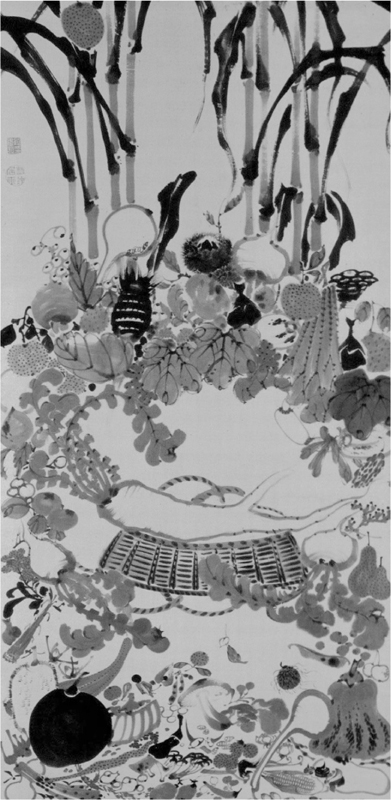

It Jakuchs (17161800) painting entitled Yasai Nehan (vegetable nirvana), for example, takes the traditional image of the reclining kyamuni passing into his parinirvana and replaces him with a daikon radish surrounded by other vegetables that stand in for the various elements of this iconic scene. Eight corn stalks take the place of the la trees under which the Buddha died, and the daikon radish is surrounded by an array of turnips, gourds, mushrooms, melons, chestnuts, and other vegetables to form the assembly of mourners who witness the Buddhas passing. Jakuchs well-attested Buddhist piety eliminates the possibility that the painting is a mere parody, and the image must be understood in the context of Japanese Buddhist and culinary history. Relevant factors include the tradition of monastic vegetarianism, the association of the daikon with the pure and rustic life, and quite importantly, the Tendai Buddhist creed that even plants and trees attain Buddhahood due to the inherent Buddha-nature in all things. It is this notion that allowed the interchangeability between the original subject (kyamuni) and other subjects, be they poets or mendicant monksor even vegetables (Shimizu 1992, 211).

The doctrine of Buddha-nature was not espoused by all Japanese Buddhists, let alone the entire Buddhist world, but it is dominant in the Mahyna-leaning regions of East Asia and Tibet. According to the rmldevsihanda Stra (The Lions Roar of Queen rml), when the tathgatagarbha is covered by defilements then it is in an embryo state, and when it is not covered by defilements then Buddhahood is a present and actualized reality (Wayman and Wayman 1974, 45). The critical idea here is that even when it is covered with defilements, the tathgatagarbha is nevertheless present. Buddha-nature is actually a translation of the term buddhadhatu (Buddha element), which is one of many synonyms for tathgatagarbha, and which emphasizes this idea that it is a quality possessed by and present in all things.

F IGURE 1.1. It Jakuch (17161800), Yasai Nehan (vegetable nirvana), ca. 1792. (Courtesy of Kyoto National Museum)

Tathgatagarbha thought is closely linked to the doctrine of emptiness ( unyat ), which deems that the dependently arising nature of all phenomena makes everything empty of inherent essence and identity. To be empty of an inherent essence may sound negative, but it is understood as the quality that enables beings to transform into a BuddhaBuddhahood is possible precisely because suffering and delusion are not inherent to human being and existence. This openness to becoming and change in a felicitous direction may be understood as the quality of the Buddha himselfthe tathgatagarbha. Understanding the truth of emptiness is a necessary precondition of the realization of tathgatagarbha and the idea of tathgatagarbha in turn corrects a one-sidedly negative perspective on the teaching of emptiness (King 1991, 16). Functioning as positive and negative formulations of the same insight, respectively, Buddha-nature and emptiness both erase the separation between the enlightened realm of nirvana and the tainted world of samsara, at least in their earlier interpretation as incalculably distant spatial and temporal domains. This also eliminates the distinction between the Buddha and other beings, and sanctions the idea that even secular aesthetic works can function as serious religious practice. This history is notable because it refrains from some characteristic anxieties regarding religious images in our more immediate monotheistic traditions.