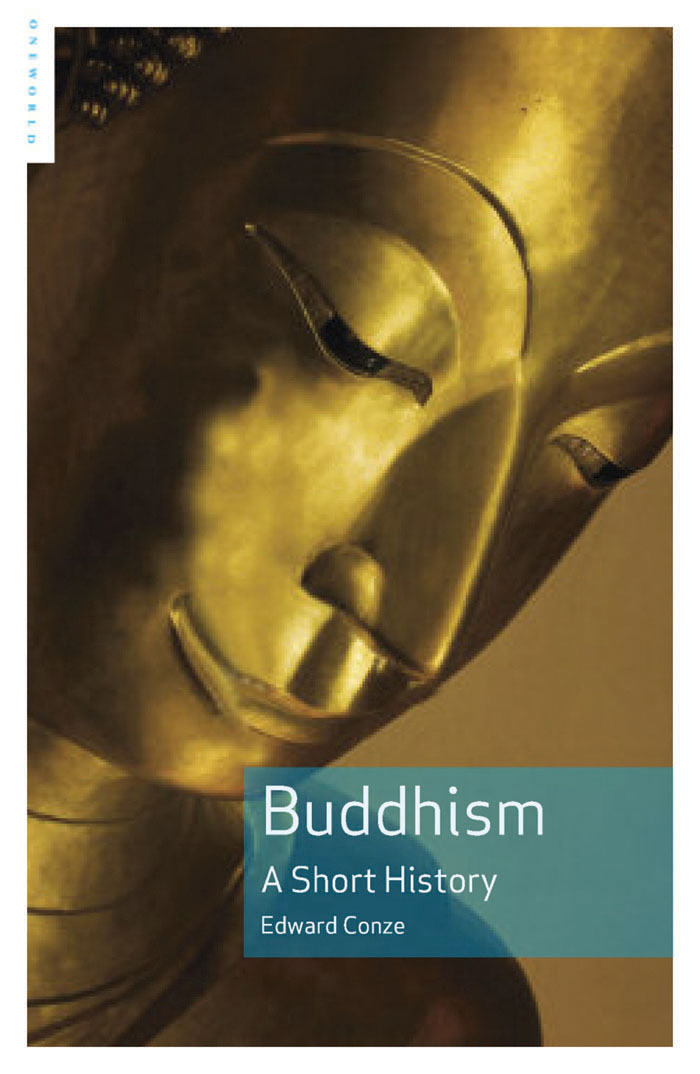

Buddhism

Buddhism

A Short History

EDWARD CONZE

A Oneworld Book

Copyright Muriel Conze 1980, 1982, 1993

First published by Oneworld Publications in 1993

This ebook edition published by Oneworld Publications in 2014

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 9781851685684

eISBN 9781780746692

Cover design by Simon McFadden

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

www.oneworld-publications.com

Stay up to date with the latest books,

special offers, and exclusive content from

Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

Contents

Introduction

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND THE EPOCHS OF BUDDHIST HISTORY

A. Buddhism claims that a person called The Buddha, or The Enlightened One, rediscovered a very ancient and longstanding, in fact an ageless, wisdom, and that he did so in Bihar in India, round about 600 or 400 BC the exact date is unknown. His re-formulation of the perennial wisdom was designed to counteract three evils.

1. Violence had to be avoided in all its forms, from the killing of humans and animals to the intellectual coercion of those who think otherwise.

2. The self, or the fact that one holds on to oneself as an individual personality, was held to be responsible for all pain and suffering, which would in the end be finally abolished by the attainment of a state of self-extinction, technically known as Nirvana.

3. Death was an error which could be overcome by those who entered the doors to the Deathless, the gates of the Undying.

Apart from providing antidotes to these three ills, the Buddha formulated no definite doctrines or creeds, but put his entire trust into the results obtained by training his disciples through a threefold process of moral restraint, secluded meditation and philosophical reflection.

As to the first point, that of violence the technical term for non-violence is ahims, which means the avoidance of harm to all life. In this respect Buddhism was one of the many movements which reacted against the technological tyrannies which had arisen about 3000 bc, whose technical projects and military operations had led to widespread and often senseless violence and destruction of life.

From its very beginning the growth of civilization has been accompanied by recurrent waves of disillusion with power and material wealth. About 600 BC onwards one such wave swept through the whole of Asia, through all parts of it, from China to the Greek islands on the coast of Asia Minor, mobilizing the resources of the spirit against the existing power system.

In India the reaction arose in a region devoted to rice culture, as distinct from the areas further West with their animal husbandry and cultivation of wheat. For the last two thousand years Buddhism has mainly flourished in rice-growing countries and little elsewhere. In addition, and that is much harder to explain, it has spread only into those countries which had previously had a cult of Serpents or Dragons, and never made headway in those parts of the world which view the killing of dragons as a meritorious deed or blame serpents for mankinds ills.

As to the second point, concerning the self, in offering a cure for individualism Buddhism addresses itself to an individualistic city population. It arose in a part of India where, round Benares and Patna, the iron age had thrown up ambitious warrior kings, who had established large kingdoms, with big cities, widespread trade, a fairly developed money economy and a rationally organized state. These cities replaced small-scale tribal societies by large-scale conurbations, with all the evils of depersonalization, specialization and social disorganization that that entails.

Most of the Buddhas public activity took place in cities and that helps to account for the intellectual character of his teachings, the urbanity of his utterances and the rational quality of his ideas. The Buddha always stressed that he was a guide, not an authority, and that all propositions must be tested, including his own. Having had the advantage of a liberal education, the Buddhists react to the unproven with a benevolent scepticism and so they have been able to accommodate themselves to every kind of popular belief, not only in India, but in all countries they moved into.

As to the third point, concerning death; there is something here which we do not quite understand. The Buddha obviously shared the conviction, widely held in the early stages of mankinds history, that death is not a necessary ingredient of our human constitution, but a sign that something has gone wrong with us. It is our own fault; essentially we are immortal and can conquer death and win eternal life by religious means. The Buddha attributed death to an evil force, called Mra, the Killer, who tempts us away from our true immortal selves and diverts us from the path which could lead us back to freedom. On the principle that it is the lesser part which dies we are tied to Mras realm through our cravings and through our attachment to an individual personality which is their visible embodiment. In shedding our attachments we move beyond deaths realm, beyond the death-kings sight and win relief from an endless series of repeated deaths, which each time rob us of the loot of a lifetime.

B. Buddhism has so far persisted for about 2,500 years and during that period it has undergone profound and radical changes. Its history can conveniently be divided into four periods. The first period is that of the old Buddhism, which largely coincided with what later came to be known as the Hnayna; the second is marked by the rise of the Mahyna; the third by that of the Tantra and Chan. This brings us to about AD 1000. After that Buddhism no longer renewed itself, but just persisted, and the last 1,000 years can be taken together as the fourth period.

Geographically, first period Buddhism remained almost purely Indian; during the second period it started on its conquest of Eastern Asia and was in its turn considerably influenced by non-Indian thought; during the third, creative centres of Buddhist thought were established outside India, particularly in China. Philosophically, the first period concentrated on psychological questions, the second on ontological, the third on cosmic. The first is concerned with individuals gaining control over their own minds, and psychological analysis is the method by which self-control is sought; the second turns to the nature (svabhva) of true reality and the realization in oneself of that true nature of things is held to be decisive for salvation; the third sees adjustment and harmony with the cosmos as the clue to enlightenment and uses age-old magical and occult methods to achieve it. Soteriologically, they differ in the conception of the type of man they try to produce. In the first period the ideal saint is an Arhat, or a person who has non-attachment, in whom all craving is extinct and who will no more be reborn in this world. In the second it is the Bodhisattva, a person who wishes to save all his fellow-beings and who hopes ultimately to become an omniscient Buddha. In the third it is a Siddha, a man who is so much in harmony with the cosmos that he is under no constraint whatsoever and as a free agent is able to manipulate the cosmic forces both inside and outside himself.