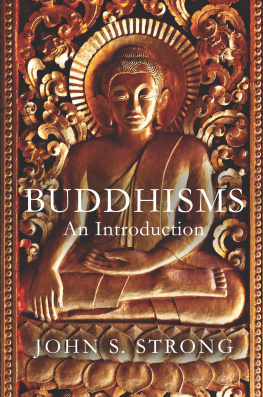

A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications, 2015

This eBook edition published 2015

Copyright John S. Strong 2015

The moral right of John S. Strong to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-505-3

ISBN 978-1-78074-506-0 (eBook)

Typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Preface

In 2005, the fifth edition of a much-used college textbook on Buddhism was published under a new title. Originally authored in 1970 by Richard Robinson, and then repeatedly expanded and significantly revised by Willard Johnson and Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey DeGraff), it had long been called The Buddhist Religion: A Historical Introduction. But with the new edition it was given a new name: Buddhist Religions: A Historical Introduction. The move from the singular to the plural in the title raises and reflects a question of primary importance in the writing of a book such as this one: is there one or are there many Buddhisms? Is the Buddhism found today in Sri Lanka (for example) similar enough to the Buddhism found in Japan, or Western Europe, or Tibet, or any other place, for them all to be said to be somehow part of the same religion?

The question is a real one. General courses on Buddhism typically start with the life of the Buddha and try to set him in his ancient Indian context. Then they talk about his teachings and the foundation of his monastic order. Then, at some point, they explain how, from Northern India, the religion that the Buddha founded gradually spread through the Indian subcontinent, to Sri Lanka, to Southeast Asia, and to Gandhra in the Northwest (in present day Pakistan and Afghanistan), and thence, via ancient trade routes, to Central Asia and China, and the rest of East Asia. However, at least in my experience, by the time the course gets to the Pure Land tradition in Japan with its stress on faithful dependence on the grace of the Buddha Amida and salvation by rebirth in his Western Paradise, and with its tradition of married priests inheriting their temples from their fathers some student inevitably asks: How is this still Buddhism? Isnt this a drastic departure from everything we learned about the religion in India at the start of the semester? It is and it isnt. And by the time the class visits Vajrayna Buddhism in Tibet with its immense pantheon of buddhas and bodhisattvas, wrathful and benign; with its kinetic visualizations of mind-made realities; with its emphases on ritual and on scholarship, and a plethora of lineages of incarnate lamas again, the question is posed: Is this still the same Buddhism? It is and it isnt. In this book, I will try to do justice to both the multiplicity and the unity of the tradition.

I wanted to try to signal this double intent by entitling my work Buddhism/s: an Introduction. Alas, in this I failed, and had to settle for the plural Buddhisms; it turns out that a slash-s runs the risk of confusing the computers that need to list this book online. (An s in parentheses is no better.) Nevertheless, although our electronics may be antipathetic to ambiguity, safe within the pages that follow I will attempt to restore that ambiguity by using the double form.

It is sometimes said that one of the things that holds Buddhism/s together is the fact that, either explicitly or implicitly, Buddhists all turn to the three refuges or triple gem of the tradition: the Buddha, his Teaching (called the Dharma), and his community (called the Sagha). At the same time, however, it must be recognized that the Buddha, Dharma, and Sagha can mean different things to different Buddhists, so that while the three refuges may unite Buddhists everywhere, they also divide them. Some, for example, see the Buddha as a singular historical personage, the human teacher who lived in India over two millennia ago and founded the religion called Buddhism. Others see him as but the most recent of a long line of masters who have periodically appeared to renew the teaching (Dharma) and reestablish the community (Sagha). Still others espouse the notion that there are an almost infinite number of buddhas spread out through space, all expedient manifestations of a transcendent truth. Or they find the Buddha (or at least the Buddha-nature) in themselves, or in things of this world such as rivers, rocks, and trees. In other words, who (or what) the Buddha was (or is) has varied radically from place to place, school to school, tradition to tradition, and time to time in Buddhist history. As we shall see, much the same sorts of things can be said about the Dharma and the Sagha. Accordingly, I will occasionally extend the ambiguity embodied in the notion of Buddhism/s and speak of Buddha/s, Dharma/s, and Sagha/s.

Schemes and Themes

With these points in mind, let me say a bit more about my approach in this book and some of its recurrent themes. Like many other authors of works such as this, I will use the three refuges mentioned above as a basic organizational scheme, but make two passes through them. After an introductory chapter (see below), I will start with some chapters on the Buddha: I will first examine, in chapter 2, not only what little we know about the Buddha historically and the world he lived in, but also varying legends about him; and in chapter 3, I will present different ways Buddhists have continued to venerate the Buddha after his passing something I call overcoming the Buddhas absence by means of relics, pilgrimages, Buddha images, and by honoring the future Buddha, Maitreya, who is yet to come. Then I will turn to look at the Dharma, examining in some detail the contexts and contents of the Buddhas very first sermon, focusing on the notion of the Middle Way (chapter 4), and on the Four (Noble) Truths (chapter 5). In chapter 6, I will start a section on the Sagha, talking about the role of laypersons and the establishment and basic structure of the monastic community, and then, in chapter 7, various kinds of divisions in that community. Following this, in part II of the book, I will begin my second pass through the three refuges, first cycling back to the Buddha, in chapter 8, to look at various ways Mahyna Buddhists have sought to find the Buddha/s not only in India, but in East Asia and Tibet as well. Then, in the next two chapters, I will pick up the story of the Dharma/s, with a look at Mahyna developments, again in India, East Asia, and Tibet (chapter 9), and with an examination of the bodhisattva path (in chapter 10). Finally, I will return to the theme of the sagha/s, by presenting a series of vignettes what I call sagha situations illustrative of the practice of three Buddhism/s: the Thai, Japanese, and Tibetan traditions (in chapters 11, 12, and 13). In each of these final chapters, I will end with an example of the presence of these traditions in the West Europe and the United States as a reminder that, in the twenty-first century, Buddhism is no longer just an Asian phenomenon.