A Natural History of Wine

A NATURAL HISTORY OF

Wine

IAN TATTERSALL AND ROB DESALLE

Illustrated by Patricia J. Wynne

Copyright 2015 by Ian Tattersall and Rob DeSalle. Illustrations copyright 2015 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Caecilia and Torino types by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in China.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015933803

ISBN 978-0-300-21102-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To our favorite oenophiles: Jeanne, Erin, and Maceo

Contents

Preface

The book youre holding is the result of an unusual collaboration between a molecular biologist and an anthropologist. As colleagues at the American Museum of Natural History, we have worked together on a number of books on topics relevant to our humanity, including the evolution of the brain and the concept of race. All of this work, of course, involved a lot of hanging out together, and since inspiration is always at a premium when we are writing a book, our head-scratching sessions have tended to be over copious quantities of wine. And once we have started drinking wine, at least a good one, the conversation naturally tends toward what we happen to be imbibing. Wine is like that: it appeals so comprehensively to the senses that it has trouble staying in the background. All those dreadful wine-and-cheese receptions notwithstanding, in its better incarnations wine is anything but a wallpaper beverage, and learning about it should not be the self-conscious, joyless burden portrayed in the movie Somm. It should at once be a fascinating, satisfying, and above all relaxing experience.

As we talked, we realized that wine holds a place in virtually every major area of sciencefrom physics and chemistry to molecular genetics and systematic biology, and on through evolution, paleontology, neurobiology, and ecology, to archaeology, primatology, and anthropology. We also came to realize how much knowing about this complex beveragewhat it is, where it comes from, and how we respond to itenhances our enjoyment of it. Hence this book, the initially unintended product of the many conversations we have had about wine, which, it turns out, has many more dimensions than either of us had suspected previously.

Of course, a book like this one is never written in a vacuum. We have benefited over the years from interactions with many wine professionals and oenophiles. On the professional side, among many others we would like especially to acknowledge our debt to Patrick McGovern, the preeminent authority on ancient wine and its composition, and to Rory Callahan, whose knowledge of wines worldwide is as vast as its dispensation is understated. Among amateur oenophiles (in the literal sense of that term), we would like to express our particular appreciation to Neil Tyson, Mike Dirzulaitis, and Marty Gomberg, all of whom have introduced us to many fabulous wines to which we would otherwise never have had access. Vivian Schwartz and Jeanne Kelly were kind enough to read and comment on the manuscript, as, very usefully, were three anonymous reviewers. The book itself could never have come about without the enthusiastic support and input of Jean Thomson Black, our editor at Yale University Press, and the patience and forbearance of Samantha Ostrowski, who shepherded it through the production process. We are indebted also to our manuscript editor, Susan Laity, who rigorously tightened up our text; and on the visual side our immense gratitude goes to Patricia Wynne, illustrator par excellence, with whom it has, as always, been a pleasure to work. We also thank Nancy Ovedovitz for the books elegant design.

A Natural History of Wine

1

Vinous Roots

Wine and People

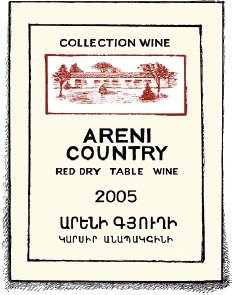

The label on the bottle didnt look like much. Areni Country Red Dry Table Wine, it said. On a wintry morning in New York City our expectations were, frankly, not too high for this obscure wine, produced in a tiny village in a remote corner of Armenia. So imagine our delight when it leapt from our glasses, all bright red fruit and black cherries, with just enough texture to leave a lingering memory that made us eager for more. Even better, it had been produced a mere kilo-meter or so up the road from the place where wine arguably began.

To find the worlds oldest winery, leave the Armenian capital of Yerevan behind you in the shadow of looming Mount Ararat and drive fast for two hours southwest. The meandering road will take you across some pretty unforgiving terrain, part of the harsh and rugged volcanic plateau that lies at the foot of the Lesser Caucasus Mountains. This is hardly the most promising of territories for an oenophile, and before too long you may find yourself despairing of ever spotting a vine amid the waste of short brown grass and eroded hillsides that stretches to the horizon in all directions. But after a while, a small green oasis will open up in front of you: a cluster of orchards and vineyards and beehives, all given life by a narrow, chattering river that seems to spring from nowhere. In the center of this lonely agricultural outpost lies the village of Areni, a small cluster of buildings that is mostly hidden by the lush vegetation surrounding it. And although the village itself is as obscure as it is tiny, its name is not. Youll see that name on bottles of wine sold all over Armenia, not because Areni itself is nowadays a major wine producer but because centuries ago this little village gave its name to what some consider Armenias finest wine grape.

Almost every wine-drinking visitor to Armenia will at some point taste a bottle or two of the deep-ruby Areni wine; and if that visitor is fortunate enough to get a really good one, its light fragrance, backed up by a firm texture, lingering ripe plum and dark cherry flavors, and, in the best of them, a hint of black pepper in the finish, will not soon be forgotten. Even an ordinary Areni is typically delicious on a hot day, poured straight from a jug kept in the refrigerator and preferably enjoyed while relaxing in the shade of one of the overflowing grape arbors with which Armenia is so generously endowed. But the people of Areni village know their wine, and they know their grape, and they probably correctly doubt that it can be grown to the same advantage anywhere else. After all, they will tell you, they have been growing these vines for centuriesfor so long, indeed, that the memory of winemaking in these parts fades back into the mists of time.

Next page