Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

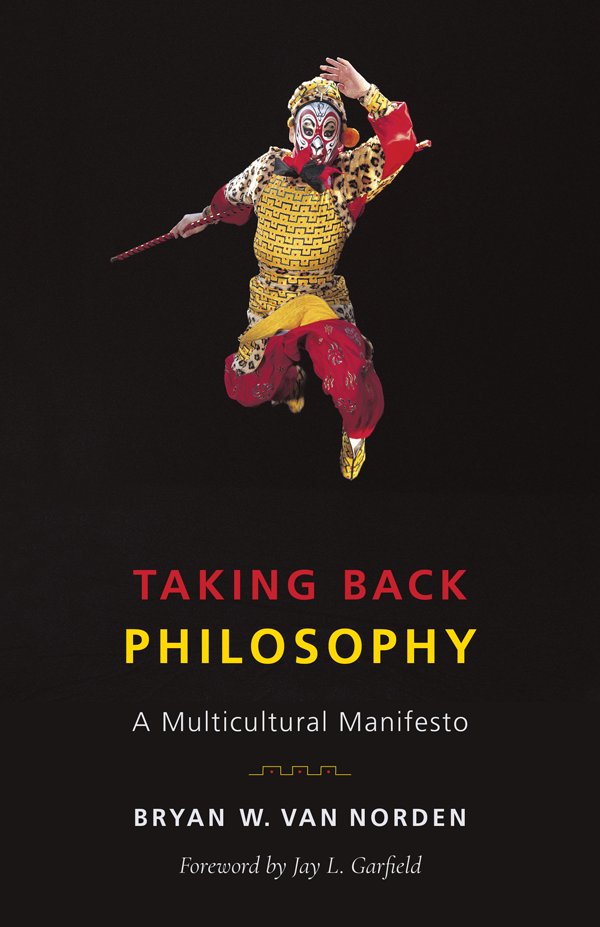

TAKING BACK PHILOSOPHY

TAKING BACK PHILOSOPHY

A MULTICULTURAL MANIFESTO

BRYAN W. VAN NORDEN

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2017 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54545-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Van Norden, Bryan W. (Bryan William), author.

Title: Taking back philosophy: a multicultural manifesto / Bryan W. Van Norden.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017031091 | ISBN 9780231184366 (cloth: acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780231184373 (pbk.: acid-free paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Philosophy.

Classification: LCC B53.V28 2017 | DDC 101dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017031091

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Cover photo: Herve BRUHAT/Gamma-Repho via Getty Images

To the Memory of

Rev. Charles E. Van Norden, DD (18431913)

our familys first philosopher

and

Warner Montaigne Van Norden (18731959)

our familys first Sinologist

I am a citizen of the world.

Diogenes

Only those who are petty regard themselves as separate from others solely because of the space between their bodies.

Wang Yangming

CONTENTS

JAY L. GARFIELD

JAY L. GARFIELD

T his book has its origins in what Bryan Van Norden and I had thought was an innocuous opinion piece in The Stone column of the New York Times , one we thought likely to be completely ignored, but which instead, to our astonishment, ignited a firestorm of controversy across the philosophy blogosphere. That column had its origin in a rather wonderful conference on minorities in philosophy, hosted by the University of Pennsylvania philosophy department, and organized by its graduate students. The graduate students and the many others who attended that conference were delightful.

Bryan and I were struck, however, by the fact that, despite including the keynote address in the regular department colloquium series, and even though the conference was held at the philosophy department, the Penn faculty almost entirely boycotted the proceedings. Most members of that department were simply not interested in hearing about non-Western philosophy, even if their own graduate students organized a conference on the topic in their own department.

We found that surprising. And out of that surprise came our short editorial, which is reproduced in of the present volume. From our previous experiences, we expected that most of our colleagues would roll their eyes and ignore it as one more lunatic fringe call for change in a field notoriously resistant to change. We hoped that a few would take us seriously and either bite the bullet and agree that their departments should be renamed or think about expanding their curriculum and hiring (and indeed a very few have taken the latter course).

We thought that a few more would offer the same tired arguments against change: It is too hard to cover the core, so how can we possibly devote scarce resources to the non-Western fringe? There just arent any good graduate programs training people in these areas, so how can we hire? We dont read the languages, so how can we seriously address these texts and traditions? We lack the expertise to determine what is good and what is bad in non-Western philosophy, so how can we hire or assess our colleagues work? What would we cut to make room for this?

We know how to respond to those rejoinders, and we find ourselves doing so all the time. Indeed, the present volume addresses these arguments carefully and in detail. But while there were a few of those in the eight hundred replies we received the first day on the Times website (a record for The Stone ) and in the thousands of others that quickly populated other philosophy sites, we were not prepared for the level of vitriol, personal attacks, and frank racism that characterized most of the replies, including many from within our own profession. Nor were we prepared for some of the spectacularly ill-informed essays that appeared subsequent to our editorial in response to it. On the one hand, we regretted having provided an occasion for some of this rhetoric; on the other hand, we are glad that it is out in the open, as it demonstrates clearly what is at stake as we consider the future of our profession. This book is a careful, if polemical, consideration of that future in response to this wave of hostility.

One philosopher wrote that Native Americans have not been literate long enough to produce philosophy; many connected Kongzi to fortune cookies; others tarred us with the brush of political correctness. (We think that it is in fact correct from a political point of view not to be explicitly racist, or even to perpetuate structural racism; we also think, perhaps charitably, that our opponents agree; one must then wonder how bad ones own position is if the best way to defend it is to concede that the opposition is correct, if only on matters of politics.) Many argued, either without citing any textual support or by providing a single snippet of some non-Western text out of context as evidence, that there simply is nothing valuable in any non-Western tradition. If this kind of argument were emblematic of the greatness of Western philosophy, then, quite frankly, we would think it is better off abandoned. Our colleagues in Asian traditions cant afford to offer such patently racist or lame arguments, and they dont.

Two responses stick in my mind. One scholar, who chose to remain anonymous, wrote that while Kongzi might have had some good philosophical ideas, China never produced a tradition of argument and commentary following his work, and so there was no real philosophical tradition in China. This is what White Privilege looks like. This author obviously knows absolutely nothing about the history of Chinese philosophy (which has a very rich and ongoing tradition of argument and commentary); she or he also presumably also knows that she or he knows nothing about that vast tradition; nonetheless, she or he feels perfectly comfortable pontificating about it in public. Imagine a Chinese scholar conceding that the West had produced Heraclitus, and that he is worth studying, but asserting that the West has no tradition of debate and argument after him.

And indeed this invocation of White Privilege is common not only among our recent critics, but among so many with whom I have discussed this issue over the years. It combines the assumption that being European, or being educated in the European tradition, authorizes one to pronounce on all things intellectual with the casual assumption that the ocean of texts with which one is unfamiliar contain nothing worthwhile, nothing worth studying, nothing worth teaching, and could not possibly measure up to Western philosophy in profundity or rigor, and even that they could not possibly be doing the same thing. One is reminded of Thomas Babington Macaulays infamous remarks: