First published in 2004 by

Nicolas-Hays, Inc.

P. O. Box 1126

Berwick, ME 03901-1126

www.nicolashays.com

Distributed to the trade by

Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC

P. O. Box 612

York Beach, ME 03910-0612

www.redwheelweiser.com

Foreword copyright 2004 R. A. Gilbert.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Nicolas-Hays, Inc. Reviewers may quote brief passages.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

Cover and text design by Kathryn Sky-Peck.

Typeset in Caslon

VG

Printed in the United States of America

10 09 08 07 06 05 04

7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481992 (R1997).

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

FOREWORD

Mysticism has been succinctly defined as the art of union with Reality, a process that involves the mystic, in a greater or lesser degree, in a direct experience of God, as he or she strives to attain the goal of such union. By its very nature, the experience, which is common to the mystics of all religious faiths, cannot be conveyed in everyday language. The manner of its expressionand its interpretationwill vary according to the culture of which the mystic is a part. Within Judaism the theory and practice of mystical experience are encapsulated in written form in the Kabbalah, a complex system of teachings, both descriptive and prescriptive, received by divine inspiration, preserved in a series of ancient texts, and supplemented by an immense number of commentaries upon them.

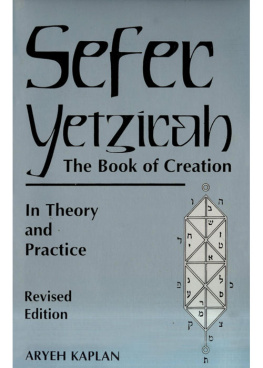

Among the earliest of these texts is the Sepher Yetzirah, or Book of Creation, that is generally, but inaccurately, known today as the Book of Formation. Gershom Scholem, the greatest of modern kabbalistic scholars, wrote of the Sepher Yetzirah that it is a book, small in size but enormous in influence. This it unquestionably is, but whether or not it relates to mystical experience is another matter. It is, essentially, a speculative text on the mysteries of creation, or, in Scholem's words, a compact discourse on cosmology and cosmogony.

The six brief chapters that make up the text present their author's cosmology by way of the magical powers and symbolism of numbers, and the numerical values and sounds of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. At the very beginning of the first chapter, the nature of the divine creative process is set out: it is mediated by thirty-two mysterious Paths of Wisdom, which comprise the twenty-two letters and ten ineffable Sephiroth, a name derived from the Hebrew word for counting. This concept of the sephiroth as agents of creation is striking and originaland it has pervaded the symbolic structures of Western esoteric thought since the 16th century, when Latin translations of the Sepher Yetzirah began to appear.

Although the text does not make their origin explicit, the sephiroth are emanationsoutpouringsthat descend or unfold from the Spirit of the Living God to gross matter. The first four are elements: spirit, water, air, and fire; while the remaining six represent directions in space: above and below, and the four cardinal points. Both the process of emanation and the nature of the sephiroth themselves have been the subject of endless speculation since the Sepher Yetzirah first appeared. One of the earliest commentaries on the text is The Thirty-Two Paths of Wisdom, which has, since the 17th century, almost invariably accompanied translations from the Hebrew.

In its essence, then, the Sepher Yetzirah is a pre-scientific attempt to describe and explain the creative acts of God. It is not descriptive of human experience of God and thus cannot be classified as a mystical text. And yet it is an integral part of the literature of the Kabbalah, which is certainly in the province of mysticism. How can this apparent paradox be resolved? First, by considering the origins of the text: who composed it, and when?

Estimates of both range widely and wildly. Before the advent of critical scholarshipand because of the references to him in the Sepher Yetzirah was ascribed to the patriarch Abraham, and even now there are those who cling to this improbable belief. liphas Lvi happily subscribed to it, but he lived in a fantastic dream world and it is impossible to separate what he truly believed from what he propagated as myths suitable for his system. More surprising is the support for a patriarchal origin given by Aryeh Kaplan, perhaps the most profound of recent students of the Kabbalah. In his edition of the Sepher Yetzirah, he states categorically that,

Fortunately, he also tabulates the dates of origin proposed by the most important kabbalistic scholars of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Adolphe Franck placed the origins of the book at the beginning of the Christian era but felt unable to suggest an author, who was, he felt, as yet not discovered. He was, however, quite satisfied that the famous Talmudist Rabbi Akiba, who was traditionally the most favored candidate after Abraham, had not compiled it. Isidore Kalisch, the first translator of the Sepher Yetzirah into English (1877) proposed a similar date, with which Knut Stenring concurs. He also accepted Akiba as the authorthus earning the dubious distinction of being the last serious student to hold this view.

Other scholars concluded that the text was more recent both Joshua Abelson and Leo Baeck placed it in the 6th century A.D.and in his introduction to the present version A. E. Waite tends to agree with them. Elsewhere, in The Holy Kabbalah (1929), Waite admits that there can be no certainty over dating the Sepher Yetzirah and evades the issue by stating that, We must be content therefore to say that the first Christian reference to Sepher Yetzirah may belong to the ninth century (p. 98).

The most thorough recent analysis of the origins of the text was made by Gershom Scholem, who concluded that, We can only be sure that [the Sepher Yetzirah] was written by a Jewish Neo-Pythagorean some time between the third and the sixth century.

What remains entirely unknown is the identity of the author, but we can speculate as to what he was attempting to achieve with his cosmological text.

Throughout the Sepher Yetzirah, the importance of certain numbers is stressed continually. The ten sephiroth are related to the digits of the two human hands, but no moral parallels are drawn (as with, e.g., the Ten Commandments), and there are three other significant numbers: 3, 7, and 12. These relate to the different types of Hebrew letters: mothers (3); double (7); and simple (12). The natures and correspondences of the letters are analyzed in detail, with emphases on the sounds of their pronunciation as well as on the numerical value. All of this has long been associated with magic, although the early academic students of the Kabbalah did not believe that this was the original intention of the unknown author. Thus Franck saw the magical use of the text as illustrating how ignorance and superstition abused later this principle... and how the so-called practical Kabbalah was formed, which gives to numbers and letters the power to change the course of nature.

It is probable, however, that this view of the author as a pious proto-scientist coming to grips with the problem of creation

Next page