Gautama Buddha

Also by Meher McArthur

Reading Buddhist Art:

An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols

The Arts of Asia: Materials, Techniques, Styles

Gods and Goblins: Japanese Folk Paintings from Otsu

Japanese Buddhist and Shinto Prints from the collection of Manly P. Hall

An ABC of What Art Can Be

Gautama Buddha

Vishvapani Blomfield

New York London

2011 by Vishvapani Blomfield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to Permissions c/o Quercus Publishing Inc., 31 West 57th Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10019, or to .

ISBN 978-1-62365-240-1

Distributed in the United States and Canada by Random House Publisher Services

c/o Random House, 1745 Broadway

New York, NY 10019

www.quercus.com

For Leo

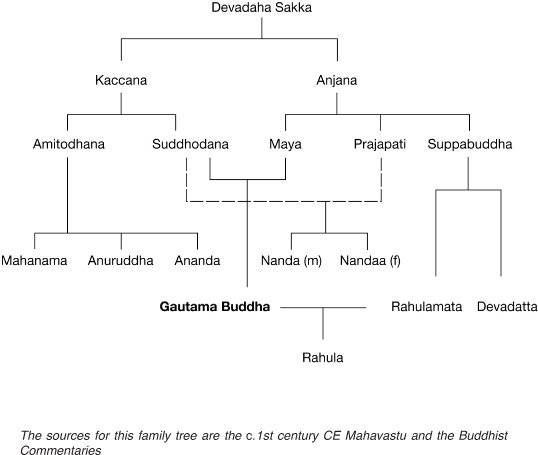

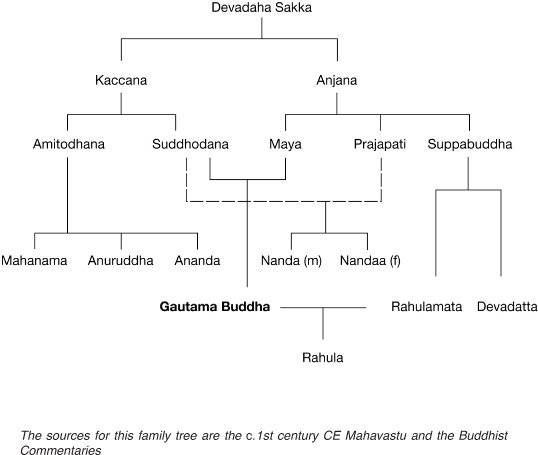

GAUTAMAS FAMILY TREE

Contents

Acknowledgments

Despite the limitations brought by his health, Sangharakshita offered advice and encouragement throughout the period of writing whenever I asked, and kindly read two completed chapters and offered his comments. For all my efforts to find fresh insights, my approach to the Buddha is essentially learned from him. Ven Analayo also read several chapters, and offered penetrating critiques in three languages, informed by his considerable knowledge of both the Nikayas and the Agamas. Dharmachari Subhuti read through the whole manuscript and, with characteristic incisiveness, illuminated many points of dharma and pointed out numerous shortcomings in my text. This book would have been very different without his generous help. Alan Sponberg (Saramati) read the final chapter and appendix and offered helpful comments from his perspective as a Buddhist historian.

I am also grateful to Dhivan and Nagabodhi, who read chapters relatively early in the writing process, and to Jayarava for his perceptive comments via email. Many other friends helped by listening to me talking about the Buddha and responding helpfully, when they could get a word in edgeways. I learned much from speaking with Stephen Batchelor, who was writing his own account of Gautamas life as I wrote this one, and highlighted for me two key issues the material throws up: how to treat the chronology of the Buddhas post-Enlightenment career, and how to present the teachings in a way that is integrated with the life. My understanding of a third issuethe need to do justice to both the human and the more-than-human aspects of the Buddhacomes from Sangharakshita. I should add that my overall understanding of Buddhism itself has developed over many years thanks to my other teachers, colleagues, friends and students in the Triratna Buddhist Order. I am also grateful to Tony Morris, who commissioned the book, and my editors at Quercus.

The house style for notes permits only direct citations, rather than acknowledgments of the scholars who have influenced my presentation. At times the debt is so considerable that this limitation is an embarrassment. The Select Bibliography cites the works from which I have learned most, but I wish to acknowledge, among recent scholars, my particular debts to Richard Gombrich, Johannes Bronkhorst, Rupert Gethin, Sue Hamilton, Geoffrey Samuel and Bhikkhu Analayo.

Over the last two decades new translations have revolutionized the relationship of English speakers to the Pali texts. I am deeply indebted to Bhikkhu Bodhi for his immense labors in translation and for the commentary and scholarship that accompanies his texts. I have also benefited from the admirable efforts of Thanissaro Bhikkhu and the staff of Access to Insight and the other internet sites that are making Buddhist texts far more easily available. Translations of Rupert Gethin, Andrew Olendzki and others are bringing a new literary subtlety to English translations of key Pali texts and I have used these wherever possible.

Finally, my heartfelt love and thanks go to Kamalagita for her support while I was writing, even when she was pregnant and caring for a new baby, and to Leo, who joined us near the end.

INTRODUCTION

Gautama and the Buddha

It is morning; the sun is hot but not yet overwhelming and a man named Bahiya scours the streets of Shravasti. His gaunt frame is covered by a rough tunic that is stitched together from pieces of tree bark and he is weary after walking night and day from Indias west coast. But he draws little attention from the townspeople, who recognize him as a holy man: a part of the tide of spiritual seekers that washes constantly through the city.

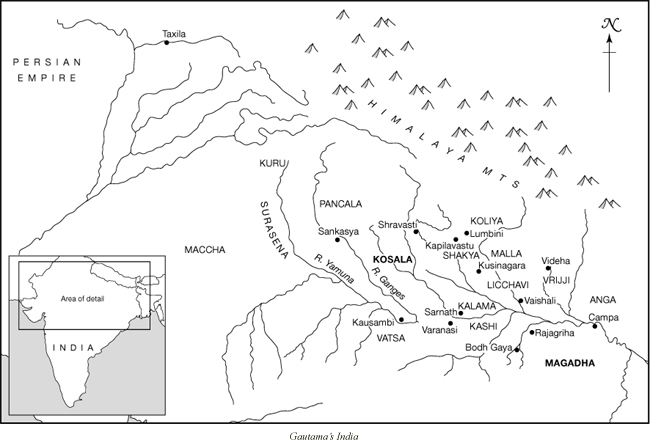

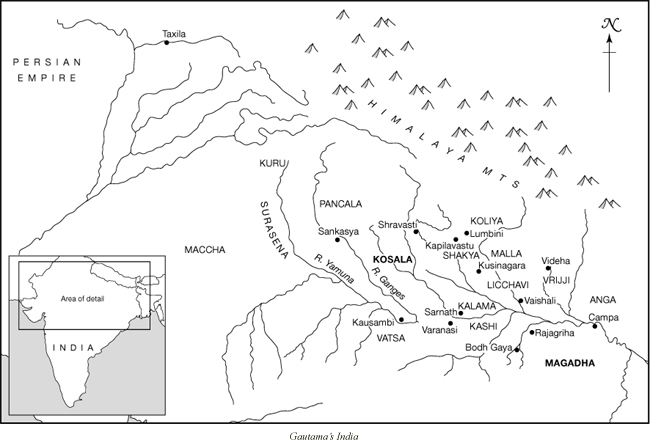

Shravasti is the capital of the kingdom of Kosala and a major metropolis of the culture that thrives in the central Ganges Valley. We have no detailed descriptions of its streets to fill out the scene, but the citys ruins have been partially unearthed and reveal that it was a large town, guarded by huge ramparts, at the junction of three important trade routes. A slightly later text evokes the profusion of such a city:

furnished with solid foundations and with many gateways and walls behold the drinking shops and taverns, the slaughterhouses and cooks shops, the harlots and wantons the garland-weavers, the washermen, the astrologers, the cloth merchants, the gold workers and the jewelers.

With such clues we may imagine the scene that confronted Bahiya: the wattle-and-daub houses with domed roofs of tiles or thatch, the sturdier brick-built civic buildings and homes of the wealthy; the main streets clogged with mules, oxen, chariots and pedestrians; the elephants lumbering impassively along the roadway laden with produce; the alleys spidering out from the main thoroughfare, thick with smells and resounding with the cries of food-sellers.

As Bahiya jostles through the press, he catches sight of a singular figure and knows instantly that it is the man he seeks. He is in the middle years of his life and the Bahiya Suttathe account of this meeting in the ancient Buddhist scripturesdescribes him as pleasing, lovely to see, with calmed senses and tranquil mind, possessing perfect poise and calm.and Buddhathe Awakened.

The encounter is intense and dramatic. Bahiya throws himself at Gautamas feet and cries: Please teach me! Teach me the Truth that will be for my lasting benefit. Gautama spoke to no one when he was collecting food, so he tells Bahiya, Come to me later and I will answer your questions. But Bahiya insists he cannot wait. It is hard to know how long you or I will live! At the third time of asking, Gautama turns to face Bahiya and speaks a few spare words:

Next page