InterVarsity Press

P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426

2016 by Makoto Fujimura

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Press is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, visit intervarsity.org.

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from THE HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION, NIV Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Cover design: Cindy Kiple

Author photo: Brad Guise

ISBN 978-0-8308-9435-2 (digital)

ISBN 978-0-8308-4459-3 (print)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fujimura, Makoto, 1960- author.

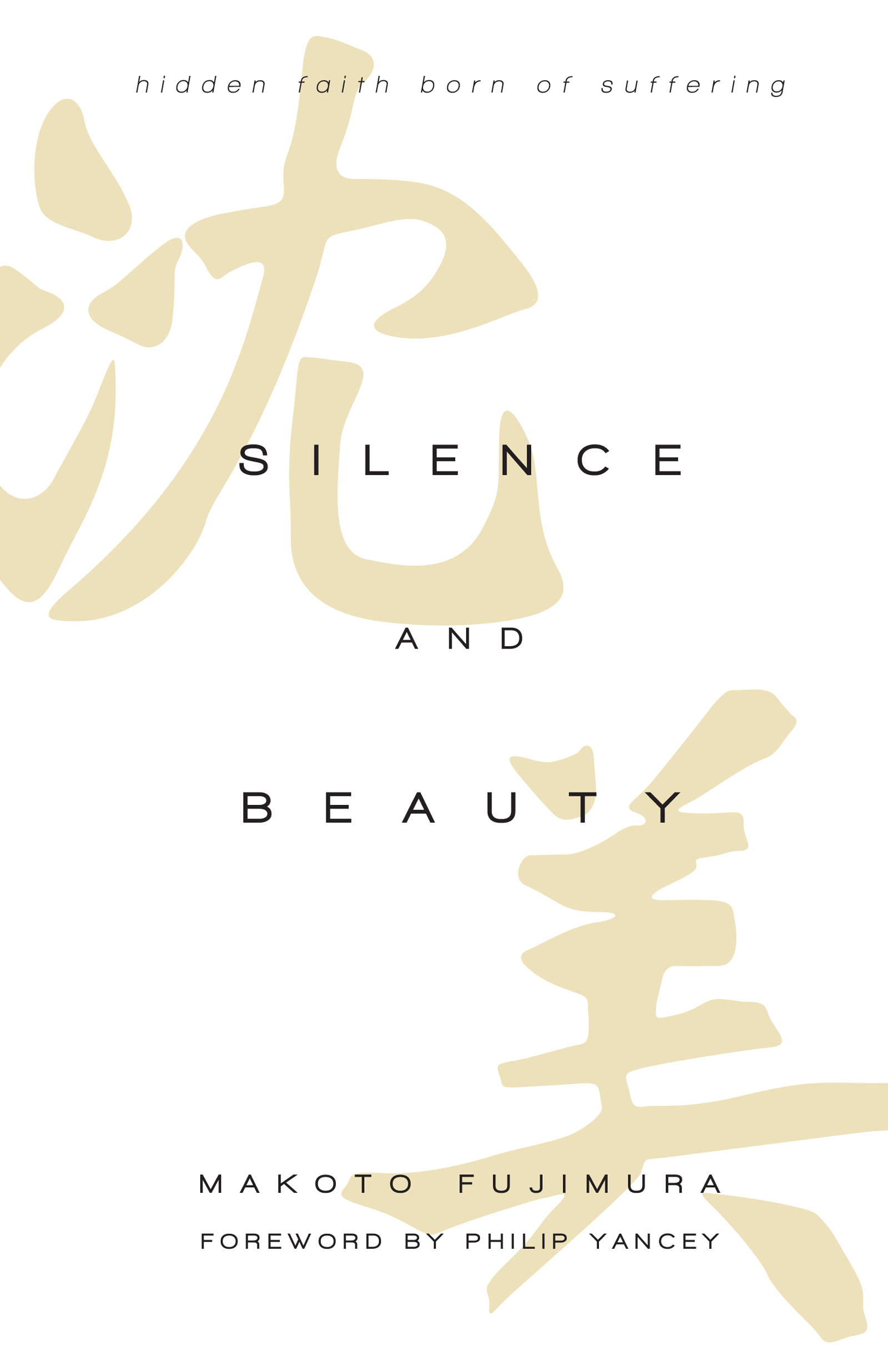

Title: Silence and beauty : hidden faith born of suffering / Makoto Fujimura.

Description: Downers Grove, IL : InterVarsity Press, 2016. | Includes

bibliographical references and indexes.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015050888 (print) | LCCN 2016011075 (ebook) | ISBN

9780830844593 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780830894352 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Endo, Shusaku, 1923-1996. Chinmoku. | Religion in

literature. | Persecution in literature. | Religion and literatureJapan.

| Aesthetics, Japanese. | Christianity and the artsJapan. |

SufferingReligious aspectsChristianity.

Classification: LCC PL849.N4 C535 2016 (print) | LCC PL849.N4 (ebook) | DDC

895.63/5--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015050888

Foreword

Philip Yancey

Christian martyrs regularly make the news. From places like Nigeria, Iraq and Syria, the media report on believers persecuted and killed by the Islamic State and other radical groups. And who can forget the scene of orange-clad Egyptian Christians kneeling by the Libyan surf, mouthing prayers, just before jihadists slash their heads from their bodies. All these join a host of martyrs from the twentieth century, which produced more martyrs than all previous centuries combined.

The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church, wrote the early church father Tertullian, and indeed in many places persecution gave rise to times of remarkable growth. But what of those who recant? In Rome, in Nazi Germany, in Stalinist Russia and Maoist China, some pastors and ordinary believers either publicly renounced their deepest beliefs or stayed silent. Who tells their stories?

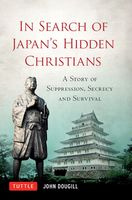

In Japan the blood of the martyrs led to the near annihilation of the church. Francis Xavier, one of the seven original Jesuits, landed there in 1549 and planted a church that within a generation had swelled to 300,000 members. Xavier called Japan the country in the Orient most suited to Christianity. Before long, however, the Japanese warlords grew wary of foreign influence. They decided to expel the Jesuits and require that all Christians repudiate their faith and register as Buddhists. To dramatize the change in policy, in 1597 they arrested twenty-six Christianssix foreign missionaries and twenty Japanese Christians, including three young boysmutilated their ears and noses, and force-marched them some five hundred miles. Upon arrival in Nagasaki, the focal point of Japans Christian community, the prisoners were led to a hill, crucified and pierced with spears. The era of persecution had begun, on what became known as Martyrs Hill.

Japanese culture deemed suicide an honorable act, and rulers feared that too many martyrs might enhance the churchs reputation and spread its influence. Instead, in a society that values loyalty and saving face, the warlords gave priority to making the Christians renounce their faith in a public display. They must trample on the fumi-e, a bronze portrait of Jesus or Mary mounted on a wooden frame, and thus deface their most revered symbols. Not just once, they had to step on the fumi-e every New Years Day in order to prove they had decisively left the outlawed religion.

The Japanese who stepped on the fumi-e were pronounced apostate Christians and set free. Those who refused, the magistrates hunted down and killed. Some were tied to stakes in the sea to await high tides that would slowly drown them, while others were bound and tossed off rafts; some were scalded in boiling hot springs, and still others were hung upside down over a pit full of dead bodies and excrement.

Mako Fujimura writes of standing on Martyrs Hill, a mile from Nagasakis Ground Zero. In one of historys cruel ironies, the second atomic bomb exploded directly above Japans largest congregation of Christians, many of whom had gathered for mass at the cathedral. (Clouds obscured the intended city, forcing the bombing crew to select an alternate target.) In the end, more Christians died in the atomic destruction of Nagasaki than in the centuries of persecution that followed the deaths of the twenty-six martyrs in 1597, for over the years by far the majority of believers had apostatized.

In the 1950s a young writer named Shusaku Endo visited a nearby museum to begin research on his next novel, which he planned to set in the devastation of postwar Nagasaki. He stood gazing at one particular glass case, which displayed a fumi-e from the seventeenth century. Blackened marks on the wooden frame surrounding the bronze portrait of Mary and Jesus, itself worn smooth, gave haunting evidence of the thousands of Christians who had betrayed their Lord by stepping on it.

The fumi-e obsessed Endo. Would I have stepped on it? he wondered. What did those people feel as they apostatized? Who were they? History books at his Catholic school recorded only the brave, glorious martyrs, not the cowards who forsook the faith. The traitors were twice damned: first by the silence of God at the time of torture and later by the silence of history. Instead of writing his intended novel, Endo began work on Silence, which tells the story of the apostates of the seventeenth century.

Shusaku Endo went on to become Japans best-known writer, his name making the short list for the Nobel Prize for Literature. Graham Greene called him one of the finest living novelists, and luminaries like John Updike joined the chorus of praise. Remarkably, in a nation where Christians comprise less than 1 percent of the population, Endos major books, all centering on Christian themes, landed on Japans bestseller lists. Now a major motion picture directed by Martin Scorsese will bring Silence, his most powerful story, to a worldwide audience.

Bicultural in upbringing and sensibility, Mako Fujimura understands the nuances of Japan, and his knowledge of the language sheds light on Endos original source material. At the same time, Makos years of living in New York have given him a contemporary, global perspective. On that visit to Nagasaki, he could not help reliving another Ground Zero experience, for on September 11, 2001, Mako was working in his studio a few blocks from the World Trade Center. And on the very day he stood on Martyrs Hill, news outlets were featuring photos of two Japanese journalists kneeling before sword-wielding jihadists, shortly before their executions. One of the two, Kenji Goto, was an outspoken Christian. Though the perpetrators may change, the age of religious martyrdom endures.