USA | Canada / UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

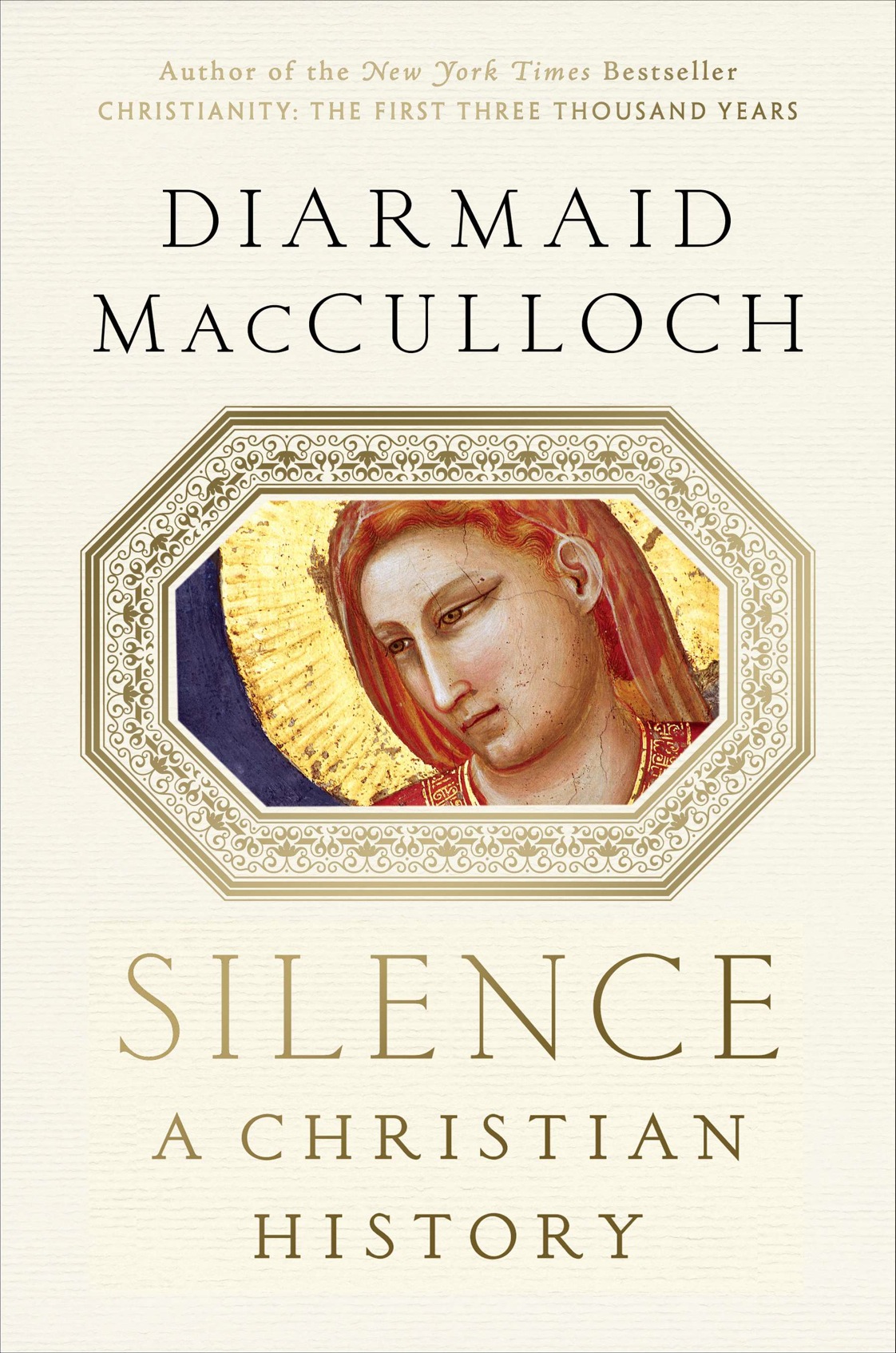

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books Ltd.

Preface and Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Trustees of the Gifford Lectures for their initial invitation to me in 2006 to give the lectures from which this book has sprung, and for their enthusiastic acceptance of my temerity in departing from their initial suggestion as to a topic for the lectures. Their hospitality in Edinburgh, one of my favourites among the worlds great cities, home to my paternal family in my youth, was much appreciated, together with the hospitality of friends who enlivened my stay during the lectures, and stimulation from the audiences who enriched the sessions with their questions and comments. I am also very grateful to the Institute of Advanced Studies at the University of Edinburgh for generously giving me an Honorary Fellowship and a study for the duration of my visit, and to the Royal Society of Edinburgh for affording me the chance of a further evening in which to engage with those interested in talking further.

In previous books, I have relegated dates of births and deaths of people mentioned in the text to the index. Here I have felt it necessary to include them in the main text, since very frequently my narrative jumps around history at some speed, and it may be helpful for some to have a sense of where they are being taken chronologically. Similarly, as in my History of Christianity, I give readers a short cut at many points by referring them back to the pages in the book where they may find a fuller explanation of what is under discussion. I apologize to those for whom it interferes with the flow of the text. Some readers may object to my frequent footnoting of my own work. I was determined to keep this book at a readable length, unlike some among my previous oeuvre, the better to reflect the texture of the lectures from which it has sprung. Self-reference is a way of saving the detailed recapitulation of arguments I have already made elsewhere, and, perhaps more importantly, avoiding needless repetition of source citations. All biblical quotations are taken from the Ecumenical Edition Revised Standard Version of the Bible (New York, 1973), including the Apocrypha/Deuterocanonical books, unless otherwise stated. I use the Hebrew and Protestant numbering of the Psalms.

As usual, in creating a book from the lectures, I have much benefited from the warm support and encouragement of my indulgent and generous publisher Stuart Proffitt and my energizing literary agent Felicity Bryan. Both Stuart and Joy de Menil, my American editor, have immeasurably improved the text by their candid scrutiny and discriminating feel for what I should have said if I had but realized it, and once more, Sam Baddeley has also brought his sure instinct for language and his sub-editing skills to the book, to excellent effect. Professor Christopher Rowland performed a great service by his reading of the resulting text and providing friendly but searching criticism. Thanks go to a mighty host for sharing their knowledge and for their generous suggestions on reading and topics on which to reflect: principal among them are Sam Baddeley, Matthew Bemand-Qureshi, Kenneth Carveley, Anna Chrysostomides, Simon Cuff, Jane Dawson, James Dunn, Mark Edwards, Philip Endean SJ, Massimo Firpo, Derek Jay, Christopher Jones, Colum Kenny, Nick King SJ, Anik Laferrire, Philip Lindholm, Jolyon Mitchell, Maggie Ross, Chris Rowland, Elizabeth Koepping, Guy Stroumsa and Ronald Trueman. Dr Hudson Davis most generously made his doctoral dissertation available to me at short notice. To those friends and colleagues I will add one now alas dead: Robert Runcie, 102nd Archbishop of Canterbury. At a time when my feelings towards institutional Christianity were not very positive, he gave me an example of cheerful, practical spirituality, rueful self-knowledge and sheer joie de vivre which all leaders in the Church would do well to ponder. His friendship was one of the most important, enlightening and enjoyable that I have known.

The most important person to thank is Sameer, who had to put up with my selfish absorption in writing this book, and who provided tireless loving encouragement in my frequent moments of despair at the task.

Diarmaid MacCulloch

Octave of the Feast of Saint Enurchus,2012

Introduction: The Witness of Holmess Dog

My favourite dog in detective fiction is the dog that did not bark in the night-time, thus affording Sherlock Holmes the vital clue for solving Sir Arthur Conan Doyles little mystery Silver Blaze. The dog who guarded the stable of the racehorse Silver Blaze did not bark, because [o]bviously the midnight visitor was someone whom the dog knew well; it was in fact the racehorses trainer, intent on villainy. I am also fond of another dog, probably a deliberate hommage to Holmes, created by G. K. Chesterton in his Father Brown story The Oracle of the Dog. The supposed oracle in question was the anguished howl of a dog who had swum out to sea to retrieve a walking stick, apparently at the exact time that the murder had taken place. Father Brown cheerily debunked the illusion that the dog had supernatural knowledge: the dog howled because it was cheated of its natural presuppositions about the walking stick. The object was in reality a sword stick, the murder weapon, and so it had sunk beneath the waves and could not be retrieved as a dog would expect of a stick. And the illusion that the howl coincided with the time of death was in fact a human contrivance.

The two tales come to the same conclusion. Conan Doyle reminds us that often one of the most significant scraps of evidence to illuminate a particular historical question is what is not actually done or said. Chestertons premise might seem the reverse of Holmess, since what is important is what the dog did, not what it did not do, but it is really the same: as he spells it out, A dog is a devil of a ritualist. He is as particular about the precise routine of a game as a child about the precise repetition of a fairy-tale. Chestertons insight is as much about human anthropology as canine psychology. Like dogs, we are pattern-making animals. The historians main task is to dig down to find these patterns, to reconstruct the crystalline structures in the actions and the pronouncements of people and to explain their meaning, as far as fragile and pattern-making human beings are capable of doing so. Only when we know the patterns well can we point out what is missing; what should be there, but is not.

Silence, then, is a vital part of what is missing in history, a necessary tool to help us make sense of the written and visual evidence that we possess. The novelist Margaret Atwood has observed that two and two doesnt necessarily get you the truth. Two and two equals a voice outside the window... The living bird is not its labelled bones. Silence is a major part of that flesh in which the bones of positive historical evidence need clothing. An example of a silence which has always fascinated me, from my first historical specialization in the sixteenth century, is the almost total absence of the Christian name Mark in late medieval and Tudor England, when the names of two of his fellow-Evangelists are common, and another, John, is overwhelmingly present. The one obvious exception which proves the rule, Anne Boleyns unfortunate musician Mark Smeaton, might explain later Tudor silence by discrediting the name because he was executed for treasonous adultery with the queen, but does not account for what went before. This is one silence, apparently trivial, yet surely significant, for which so far I have found no good explanation. If we were to solve it, we might learn something new about the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.