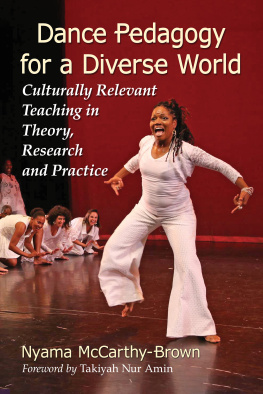

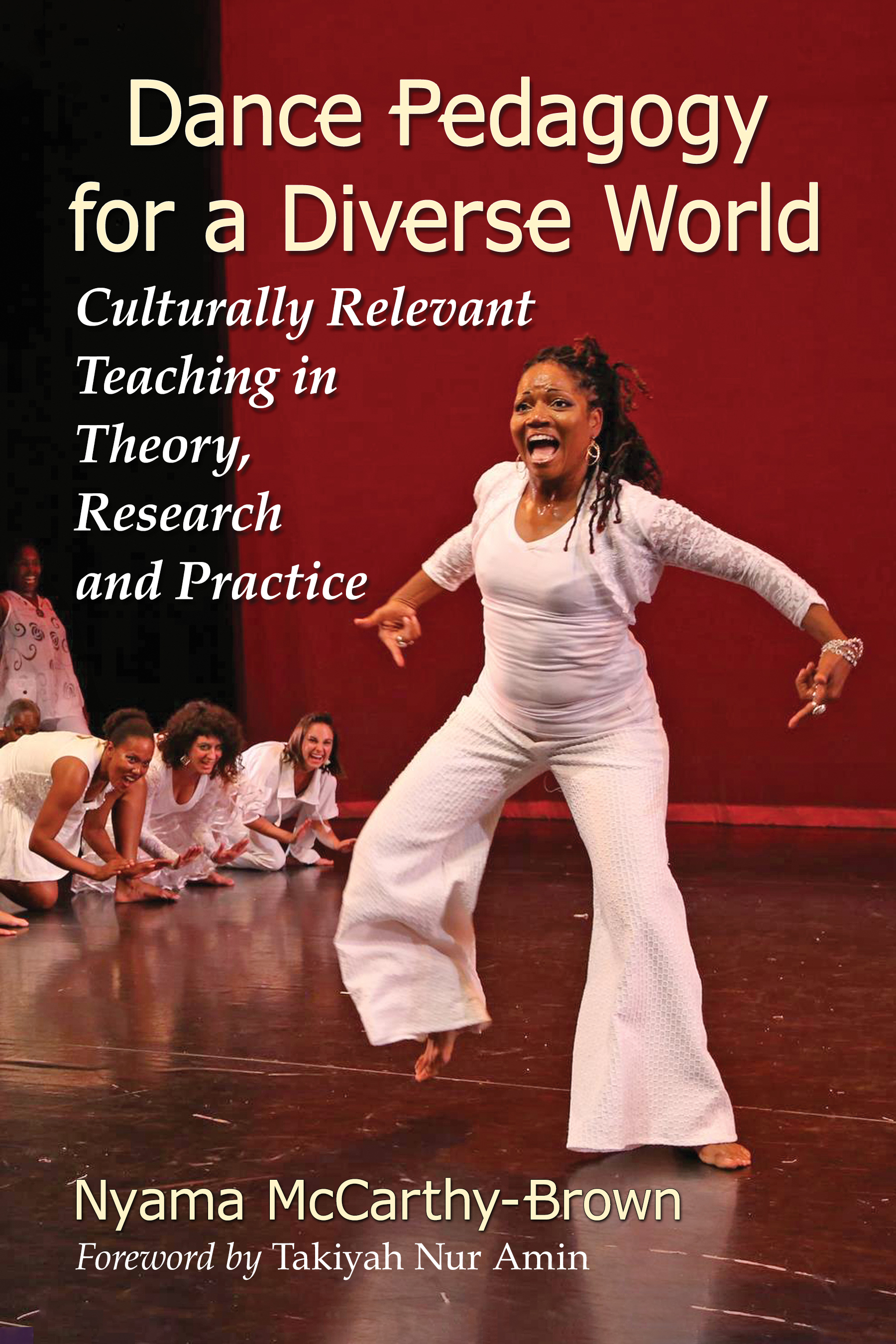

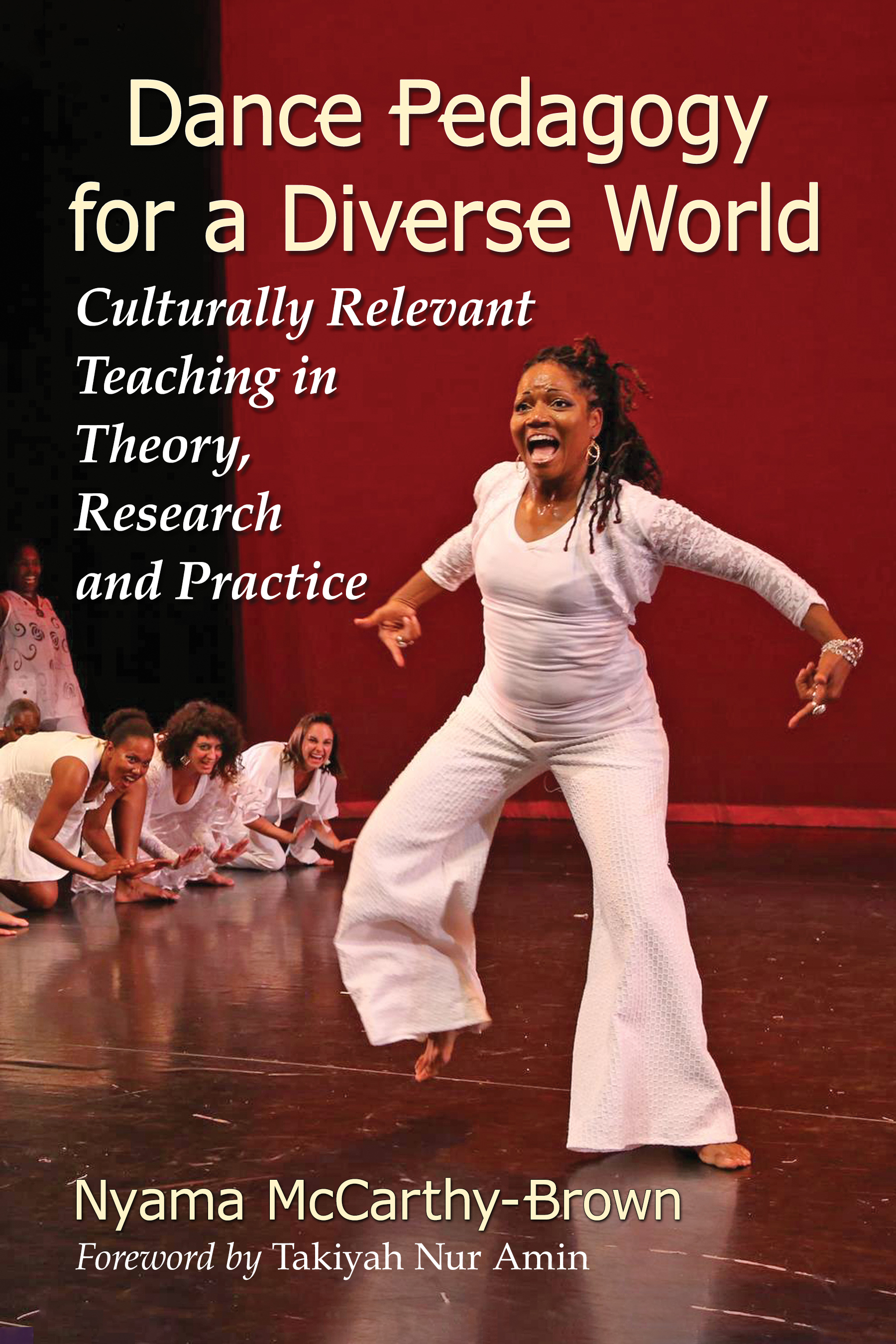

Dance Pedagogy for a Diverse World

Culturally Relevant Teaching in Theory, Research and Practice

Nyama McCarthy-Brown

Foreword by Takiyah Nur Amin

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2607-9

2017 Nyama McCarthy-Brown. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover in front Magi Ross, kneeling front row left to right Janira Bremner, Fania Tsakalakos, Kiera Mersky, second row Rhonda Moore, third row Cheryl Hinton (photographer Bill Hebert)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To those who unapologetically dance the dances

of their ancestors: May you dance on, and may

those who watch know that they bore witness

to the essence of humanity.

Acknowledgments

As I come to the close of my time preparing this manuscript, I am struck with gratitude thinking of the many people who have invested energy into this book. I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge the support of countless people, friends, family, and colleagues who stimulated and propelled this work. Dialogues with students and teachers in the field of dance and education inspired many of the ideas developed herein as well as the investigations of my graduate school classmates both at the University of Michigan and Temple University. Sherrie Barr was the developing editor, without whom this text would not present the rigor and balance of ideas it does. Kariamu Welsh was instrumental in sharing insights on Dance Education and the publication process. Mentorship was extended to me by Tommy DeFrantz in responding to the work as well as colleagues Karen Schupp, Stephanie Power-Carter, Selene Carter, and the Mellon Dance Studies Seminar Community of fellows and advisors.

My deepest gratitude is extended to my number one and first supporter, my mother, who spent hundreds of hours reading every draft of every chapter, again and again, often because she was unable to save on her computer or the file she revised did not attach or send when emailed to me. Without complaint or a hint of annoyance, she graciously read, re-read, and read again, providing needed feedback with each revision.

I offer sincere appreciation to each of the contributors to this text: Takiyah Nur Amin, Selene Carter, Julie Kerr-Berry, Kelly Fayard and Corrine Nagata. These individuals generously shared their research and teaching discoveries through the creation of an original essay for this book. Their commitment to the field is evident in their scholarship.

Finally, I wish to extend a special thanks to my students, who taught me the value of critical dance pedagogy and culturally relevant teaching. Without my students this work would not be possible, and it is for dance students everywhere that this work was created.

Foreword by Takiyah Nur Amin

Whether I am interacting with colleagues at my university, chatting with family members at social gatherings or engaging with friends near and far on social media, I am confronted by one simple, oft-repeated and taken-for-granted refrain. The world is changing.

In the wake of consistent and highly visible protest aimed at racist social policies in the communities of Ferguson, Baltimore, Charleston and across the country, it seems that friends, family and colleagues alike are convinced that we are moving into a new eraa new world, one that requires a reorienting of our relationship to both self and other. As the democratization of information proliferates through online mediums like Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook, and other platforms, the possibilities for growing awareness of social and political change and consequently global action have become increasingly commonplace. I marvel at how quickly informationwhether it is an article that synthesizes the commonalities between youth protests in Palestine and the #blacklivesmatter protests in the U.S. or tweets that amplify the lived experiences of native-born black women in Africahas become a part of not only my regular information diet but is also referenced easily by students, family and peers. Perhaps the world is changing. I remain unconvinced.

Sure, the social and political landscape around us is different than it was a decade ago. One can point to everything from shifting demographics, rising protests, the toppling of long-standing regimes and changing public sentiment around symbols once believed benign by many to see that yesterday and today are not the same. Still, I am not sure its the world that is changing as much as our understanding of the complexity around us that is in flux. It feels more accurate to suggest that with increased access to media and information for many and the possibility for communication across perceived boundaries, our ever-changing world requires that we make space for nuance, challenge assumptions, assimilate information once overlooked and engage in the re-making of ourselves to attend to this re-making of our world.

If this is true, how are those of us committed to Dance Education going to equip ourselves to engage students meaningfully as we strive to make sense of the relevance of our practice in this new context? What do we need to do as educators to ensure that this changing world does not leave us behind in a heap of outdated methods and ways of thinking, best suited to some other time and place? How do we help our dance students make sense of living in an increasingly mediated, intensely diverse world, with all of its ambiguity, messiness, unrealized ideals and untapped potential?

An anecdote: Ive been teaching in higher education settings for over a decade and in community settings before that. I am always struck when students enter my classroom with a palpable enthusiasm and obvious anxiety about being in the course. It isnt because of what theyve heard about my reputation as a professor or some concern about the syllabus. These students articulate that they are really excited about taking my class and looking forward to the course but they dont know anything about dance. Once I probe deeper, what becomes apparent is that not know[ing] anything abut dance means they have not studied and been trained to proficiency in Western and historically privileged dance forms. Not knowing modern dance or ballet has become shorthand for not knowing anything about dance at all. These students, quick to dismiss their own embodied experience and cultural knowledge in favor of what they think my university classroom and role as a professor will privilege, has become a sad and all too familiar experience for me as a dance educator. I do my best to disrupt this faulty notion and assure the students that not only are they welcome in the class, they are also encouraged to bring themselvesincluding their lived experiences with dance and movementto the course we are endeavoring through together.

Heres the thing: as dance educators, we have to do more than disrupt this kind of faulty thinking that disregards ones own cultural experience in favor of something deemed of higher value. Sure, many of us may have lived in this field for decades referencing our own training experiences that upheld similar value judgments. Sometimes weve celebrated our own teachers who, no matter how well-intentioned, were in many instances neither considerate of nor committed to teaching in a manner that held an emancipatory ethic or even considered the possibility that the movement vocabularies of their studentsacross race, class, gender, sexuality, region, and nationcould be of merit, except as the occasional accent to the serious work of their classrooms. Even some of us who champion bringing forward less lauded movement vocabularies and their attendant philosophies into our classrooms need to do a better job of considering how to value the lived, embodied knowledge our students carry and how it connects with and can inform whatever it is we are endeavoring to share with them.

Next page