In the beginning, Eurynome, the Goddess of All Things, rose naked from Chaos, but found nothing substantial for her feet to rest upon, and therefore divided the seas from the sky, dancing lonely upon its waves. She danced towards the south, and the wind set in motion behind her seemed nothing new and apart with which to begin a work of creation. Wheeling about, she caught hold of the north wind, rubbed it between her hands, and behold! the great serpent Ophion. Eurynome danced to warm herself, wildly and more wildly, until Ophion, grown lustful, coiled about those divine limbs and was moved to couple with her. So Eurynome was got with child. Next, she assumed the form of a dove, brooding on the waves, and, in due process of time, laid the Universal Egg. At her bidding, Ophion coiled several times about this egg until it hatched and split in two. Out tumbled all things that exist, her children: sun, moon, planets, stars, the earth with its mountains and rivers, its trees, herbs, and living creatures. (The Pelasgian Creation Myth, Greek Myths, Robert Graves, 1955.)

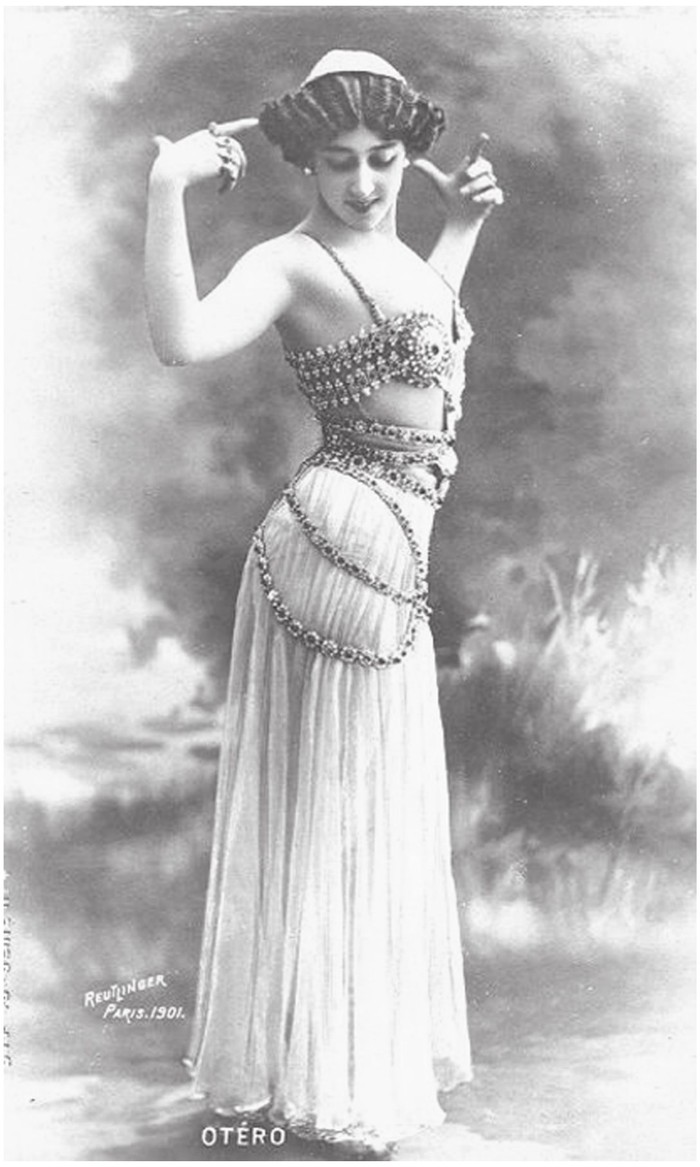

Throughout history, human beings have used dance to sustain their link with the cosmos and to communicate with their gods as they celebrated the life force and renewal of nature. Evidence tracing the earliest recognisable dance forms back as far as 13000 BCE is provided by the famous cave paintings of Chauvet in France, for example, which depict a sorcerer with arms raised and legs set apart, apparently dancing. Together with more recent depictions, such as the Dance of the Goddess and Young God Beside The Tree of Life from the Mycenaean Ring at the Tholos Tomb of Vapheio 1450 BCE, such evidence enables us to trace the evolution of fledgling dance forms (The Myth of The Goddess, Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, 1991). From such representations we can conceive of the basic rhythmic motion used by early practitioners to worship the gods and chart the development of these primitive dance forms into complex mystical, magical and religious cults involving a variety of ceremonies.

Early dance movements were imitative, achieved through the dancers awareness of their environment and through their observations of the birds and animals around them. By mimicking the characteristic movements of these indigenous species, such as their mating rituals, an imitative dance form was created that forged a rhythmic release of energy through which the dancers displayed an involuntary expression of emotions such as ecstasy and pleasure.

It is easy to visualise how imitative and mimetic dances were performed by our ancestors when basic movements such as leaping, jumping, lunging, squatting and circling are all familiar characteristics of animal behaviour. The uniquely human aspect, however, is that through imitative dance human beings found themselves able to express their joy, grief and physical desires in order to re-live the daily dramas of their lives. Subsequently, over time movements became more complex, varied and rhythmic, creating art forms that Curt Sachs described in his book, World History of the Dance (1937), as the mother of all arts.

The various representations of dancing figures found in cave paintings suggest that primitive dance forms played an extremely important role in the social life of our ancestors, who believed that spirits and demons surrounded them and were capable of doing great harm. Without the benefit of science, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and hurricanes, thunder and lightning, rain, floods and winds, the rising and setting of the sun, the waxing and waning of the moon and even the occurrence of night and day would have remained mysterious. To these ancient people the volatile nature of the cosmos and the natural world was both inexplicable and frightening.

In consequence, humans used magic rites and witchcraft to worship the gods, and, with the help of sorcerers, attempted to appease the angry or hostile gods they believed had caused the catastrophic natural changes they endured. They believed that the gods had inflicted terrible diseases on them, injuries, sickness and hardship that resulted in disability or death. Magicians or medicine men were revered almost universally in early societies as the healers of disease and the leaders of men. In fact, in certain societies where shamanism remains prominent today, in some Inuit and Siberian cultures for example, sorcerers continue to be regarded as the most powerful members of their community (The Myth of The Goddess, Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, 1991).

The first dances were an essential part of worship through which human beings felt they were able to establish their relationship with divinity and a unification of the earth with a higher, spiritual world. Through dance they manifested the ethereal sphere of gods, spirits and demons in a form of ritual worship from which it is said religion was born (Greek Myths, Robert Graves, 1955).

For our ancient ancestors, nothing equalled the power of dance as a form of ritual worship and magical representation. Dance was also a means of establishing divine intervention, to enable good to be distinguished from evil, and a means of protecting themselves from destructive influences. As the primary concern was the cycle of life, dances were performed ecstatically for all occasions. They celebrated birth, death, rebirth, planting and harvesting, as well as victory in war and a successful hunt. The sacred dance was also a way of evoking the animal soul of humanity, for it was considered vital to maintain a healthy relationship with the unseen powers of life believed to be embodied in the animals surrounding them (The Myth of The Goddess, Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, 1991). To this end our ancestors often wore the skins of the animals they had hunted, depending on which animal a ritual focused on. Dance was necessary for initiating the young on reaching puberty and for courtship rituals and fertility rites, which sometimes exploited the hormonal changes induced by lunar activity. C. Knight suggests in his book, Blood Relations (1991), it is possible that, by using the moon as a clock and by dancing in time with it, palaeolithic women succeeded in keeping in synchrony with one another, thus regulating menstruation and ovulation. So early dance forms included rain dances, sun and moon worship and supplication to the gods. Dance enabled these humans to enhance the structure and quality of their lives and ritual ceremonies were linked with magical, religious and cultural beliefs.

There is evidence of circle dances and double-circle dances in which the women formed the outer circle and the men the inner circle. In depictions of Stone Age dances from the caves of Tuc DAubert and Montespau in South West France, for example, a clear imprint of feet forming a circle have been found. These dances were thought to represent the celestial motion of the moon and the sun and to protect a divine space from intrusion. Spiral dances represented death and rebirth, mimicking the journey of the dead by weaving along a winding path that represented the wandering of the soul.

Circle dances were followed by line dances in which men and women faced each other in rows and repetitively danced towards and then back from one another. In its more recent manifestations the circle dance has altered so that the dancers should not actually take the hand of their fellow dancers but instead link together by holding the corner of a handkerchief (