Egyptian Belly Dance in Transition

The Raq Sharq Revolution, 18901930

Heather D. Ward

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2963-6

2018 Heather D. Ward. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

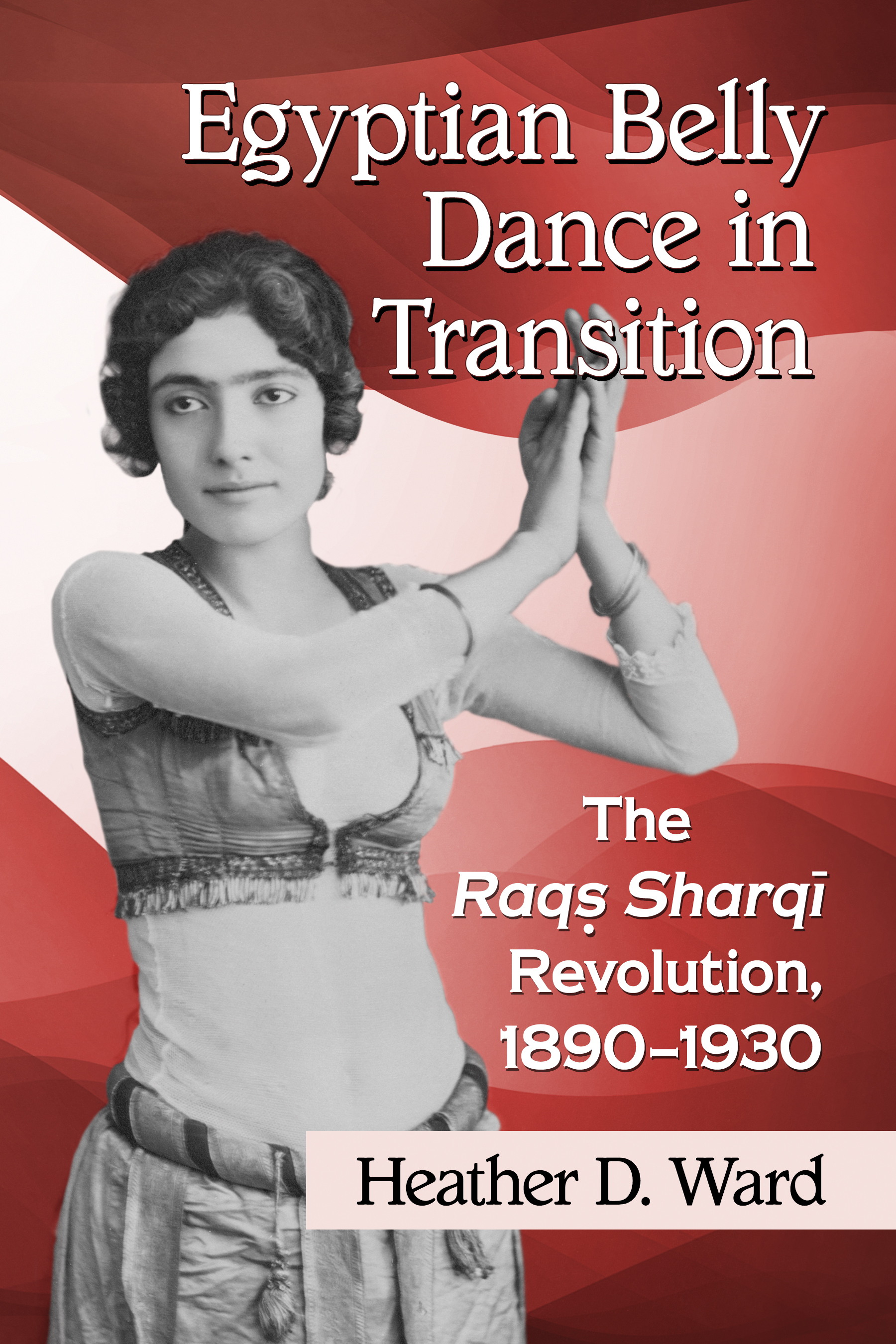

Front cover image: Danseuse circa 18601929 (G. Lkgian & Cie., photographer, New York Public Library)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Preface

My involvement with raq sharq, i.e., belly dance, began in 1999, while I was a graduate student in anthropology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. My story begins in a manner quite similar to that of other American women who find their way into the dance. I knew very little about itI was primarily drawn to it for its exoticism, and because it provided me with an escape from a personal life that was in turmoil and an academic life that was stretching my coping mechanisms to their breaking point. As someone who was not particularly at home in my own body and who had never really felt comfortable with physical activities like dance and sport, belly dance was tremendously liberating, allowing me to connect with my body and to claim it, in a sense. In my mind and in my heart, the dance existed for me and for my personal fulfillment, and for the first nine months or so of private lessons, I kept my hobby a secret, even from family and close friends.

Because of the manner in which I entered the world of belly dance, my academic training and my dance training did not really intersect in any meaningful way for several yearseven as my involvement with the dance deepened to the point that I began teaching classes for others. I accepted, without analysis, the information provided to me by well-meaning instructors, who proclaimed that belly dance was by women, for women, an ancient dance, a dance born out of a sacred connection to the mysteries of womanhood and femininity, and I gobbled up popular belly dance literature that reified these assertions. Not coincidentally, these narratives aligned well with my emotional and psychological needs at the time.

By 2005, the dance was integral to my life. It had been an anchor for me through several of the most troubling years of my life, and had helped me to emerge from the chaos a more stable and self-assured person. However, as I settled into this new era of clarity and stability, I had time to reassess my understandings of the dance that had led me to this place. Doubts about the common knowledge that I had long accepted began to nag at me, and for the first time, I began to apply my academic training to an examination of what I (thought I) knew. I was disturbed and distressed to find little evidential support for a lot of what I had been taught and what I had unquestioningly repeated to my own students. Moreover, I was deeply troubled by the fact that, in using belly dance to satisfy my own needs, I had carelessly embraced self-serving Orientalist narratives about the dance and its history, while neglecting the perspectives of Egyptians regarding their own dance.

As I leveraged my academic background toward a better understanding of the dance I loved, I found that my affection for belly dance became deeper, richer, and more authentic to my personality. I started to delve into what little academic work on the dance that I could find, and I discovered the reality of the dance to be even more captivating than the fantasy vision that I had previously embraced. I began listening in earnest to the voices of Egyptians and Arabsnot only professional dancers, but also ordinary individualsin order to grasp their perspectives on belly dance, which turned out to be complex and, in many cases, conflicted. I started corresponding with Priscilla Adum and the late Dr. Hishm al-Ajam, individuals who shared my interests and who inspired me to turn my attention toward exploring Arabic-language sources.

As I entered this new and exciting phase of my involvement with belly dance, I heard of a new course being offered by the well-known dancer and researcher Sahra C. Kent. This course, which she christened Journey through Egypt, was intended to be precisely thatan academic foray into the diverse dance traditions of Egypt, combining lecture, discussion, demonstration, practice, and, ultimately, on-site study in Egypt. I was immediately interested, and I scrimped and saved in order to attend the first level of this course. In 2009, I set off to Escondido, California, nervous and unsure what to expect. When the course began, I knew I had made the right decision. I was spellbound: here we were, discussing Egyptian dancesincluding belly dancefrom an academic, empirically-based perspective. The portions of the course that discussed the awlim and the ghawz, Egypts original professional dancing women, sent my mind racing with thoughts and questions regarding the history of belly dance. How and when did the dance styles of these women come to be transformed into the belly dance that I recognized? And why? I was determined to get answers to these questions.

I commenced with my own focused research into belly dance history, and I continued with Sahras course, eventually completing levels two through four, a process that at long last brought me to Egypt. As I stood on Egyptian soil, I felt that I had found myselfI was not only a belly dancer, but I was a belly dance researcher. My academic training and my dance training had finally been woven together, and I had a clear missionto seek out the evidence that would at long last allow an empirically based examination of the emergence of raq sharq.

My research interest in early raq sharq prompted me to dive headlong into nineteenth and early twentieth century primary sources such as turn-of-the century travel guide books and Arabic-language newspapers and magazines. It also had the side-effect of initiating my hobby of collecting period photographs, postcards, prints, and ephemera related to Egyptian entertainers and entertainment venues. These items have proven to be a boon to my investigations.

I did not initially plan to write a book based on my research. However, around five years into my investigations, I realized that I had collected sufficient information to draw the various lines of evidence together into a coherent and detailed narrative regarding the origin and early development of raq sharq. I began to feel a sense of obligation to share what I had learned. I recalled my own beginnings in the dance, and I realized I did not want another student to have to stumble through a forest of misinformation for years before finally arriving at some factual information about the dance. Moreover, my own early experience with belly dance reminded me how casually commonplace it has been, among non-Egyptian practitioners of this dance, to detach the dance from its cultural context and to manipulate and distort its history. I felt a responsibility to draw attention to Arabic-language primary sources, and in doing so, to the perspectives of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century Egyptians who created this dance form. For these reasons, I made the decision to start writing, and this book came to be.

Next page