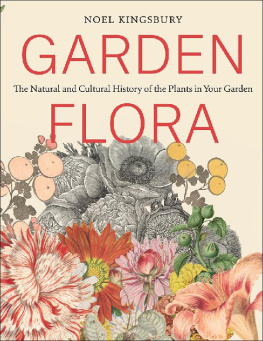

NOEL KINGSBURY

GARDEN

The Natural and Cultural History of the Plants in Your Garden

FLORA

In memory of Nicky Daw (19512016),

whose garden at Lower House, Cusop,

near Hay-on-Wye, Wales, created over many

years with her husband, Peter Daw,

gave inspiration to many.

Contents

Introduction

Read this first!!

Every garden plant comes from somewhere. It will have ancestral species growing on a mountainside or deep within a forest, or be part of some great remaining grassland. These ancestors may well have been put to some use by the local community, as food, medicine, or source of materials; they might have played a part in local mythology or spirituality. But at some point in history they were taken into cultivation and then truly become part of the human story. Some plants have been transformed by cultivationselected, crossed, and bred to a level where their wild ancestors can hardly be recognised. Others have stayed remarkably similar to what might still be found in the worlds diminishing wild spaces. But when were these plants introduced into cultivation? Where, when, and how did we end up with the range of cultivars we currently have down at the garden centre or nursery? This book is intended as an overview of the most widely grown genera of temperate zone garden plants, answering not just questions about origins and habitats but offering a broad outline of their history in cultivation as well.

Books on how to cultivate garden plants are plentiful, and many of these (as well as an increasing number of online sources) discuss the basic botanical characteristics of genera common in cultivation. These are two areas which are not dealt with here. What is much more difficult to access is information on the ecological aspects of garden plants and on their history in cultivationareas that this volume focusses on. In addition, to help fill out the picture and provide some extra colour to our experience of garden plants, some reference is also made to the mythological and folklore aspects of garden plants, where relevant, and to their traditional and modern uses outside the garden.

The information available on the ecological and historical aspects of garden plants is very patchy: there is a lot on some genera, very little on others. This is partly a reflection of geography and development; it is easy, for example, to find material on the ecology of European plants, very difficult for Chinese. In some cases very detailed studies have been made of some genera, whereas others have been ignored. What I have tried to do is the classic standing on the shoulders of giantsreflecting upon and making available scholarship that is not available elsewhere, in one volume. In most cases, the genus is the unit of discussion; the exceptions are a number of headings that discuss a larger taxonomic unit or a cluster of genera (e.g., asters, gesneriads, heathers).

This introduction is aimed at talking the reader through some basic concepts, using keywords, which are here emphasised in bold. These keywords will then be used throughout the book as a shorthand. In many cases these concepts can only be understood in a wider context; consequently, the content here will act as a very basic primer in plant ecology and in garden plant history. Certain key personalities (plant hunters, botanists, etc.) who are repeatedly referenced, often by surname only, will also be indicated here in bold. Readers should be able to refer back to this introduction to find explanations of keywords.

The Genus

The first part of each entry in this book is designed to give the reader a broad overview of the genus: the origin of its name, its size (in terms of species) and native range, and the form the plants take. For gardeners who have got beyond the basics, the name of a plant genus is a kind of keystone for our understanding of plants, of making some sort of sense of them in our minds and for communicating with others about them. With complex genera, of major garden importance, there follows a breakdown of the often bewildering array of subcategories, which gardeners and botanists have used to try to bring some order to what often seems like chaos.

Wild plants exist as species; each has a binomial scientific name (genus + species), initially developed by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (17071778). Many garden plants, however, are cultivars, not natural species. Cultivars are often selections from a single species, of which every individual is genetically identical; many cultivars are hybridsthe result of a cross between two or more distinct lineages (which could be species, cultivars, or other defined and distinct groupings below species level). Taxonomic unitsspecies, subspecies, cultivarare collectively referred to as taxa (singular, taxon).

Ok? With this little bit of knowledge, much of the apparent complexity of plant naming falls into place. We could go on: the family is another very useful categorisation concept, and this too is stated for each plant entry. Very useful categorisation conceptactually Im having second thoughts about this, as several times here I find myself referring to recent changes in families, a result of the advanced (and mind-numbingly complex) field of phylogeny (the study of evolutionary relationships), which is using DNA-based (and other) data to do a lot of reclassifying. Many familiar families are being reorganised in a way that goes against many of our deepest intuitions.

Plant growth habit

Trees, shrubs, climbers, annuals, biennialsall are well-understood words, although we will be discussing some qualifications. Perennial is a bit ambiguous, as technically it covers any plant form with a long lifespan; here we follow the popular parlance of using it for longer-lifespan herbaceous plants. Herbaceous refers to the habit of dying back every year in the winter, or the dry season, as opposed to woody plants, which accumulate growth from year to year. Subshrubs is not a botanical term but a very useful one for gardeners, as we seem to be drawn to these low-growing, semi-woody shrubs, with their pleasing rounded shapes and (nearly always) evergreen foliagelavender is perhaps the best example of one. Lianas are large climbers with woody stemseffectively, trees that cannot stand up straight. They are what Tarzan swings on.

Bulbs, corms, and tubers will be referred to collectively, using the technical term geophyte. This is one of those not-very-user-friendly words (try rephrasing Wordsworths famous poem about daffodils, When all at once I saw a crowd, / A host of golden geophytes), but it makes sense, a good way of describing all those plants which can be conveniently sold dried in packets at the garden centre. Similar, but not so easily packaged up, are spring ephemeralsperennials that have a short spring growth period but die back in summer. Geophytes and spring ephemerals maximise the benefits of a limited season of light, moisture, and nutrients before the competition of surrounding plants and the constraints of the environment reduce these key inputs to plant survival.

Most garden plants are terrestrial: they grow on the ground. In some warmer, humid climates or growing conditions, however,

Next page