About the Book

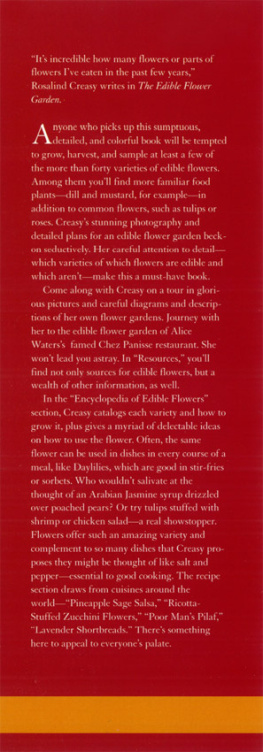

In high-end restaurants and in the home, more and more cooks have discovered the joy of using natural, foraged ingredients. But what few realise is that you dont necessarily have to go rootling in hedgerows or woodlands to find them.

Many of our own gardens contain an abundance of edible and medicinal plants, grown mainly for their ornamental appearance. Most gardeners are completely unaware that what they have actually planted is a rather exotic kitchen garden.

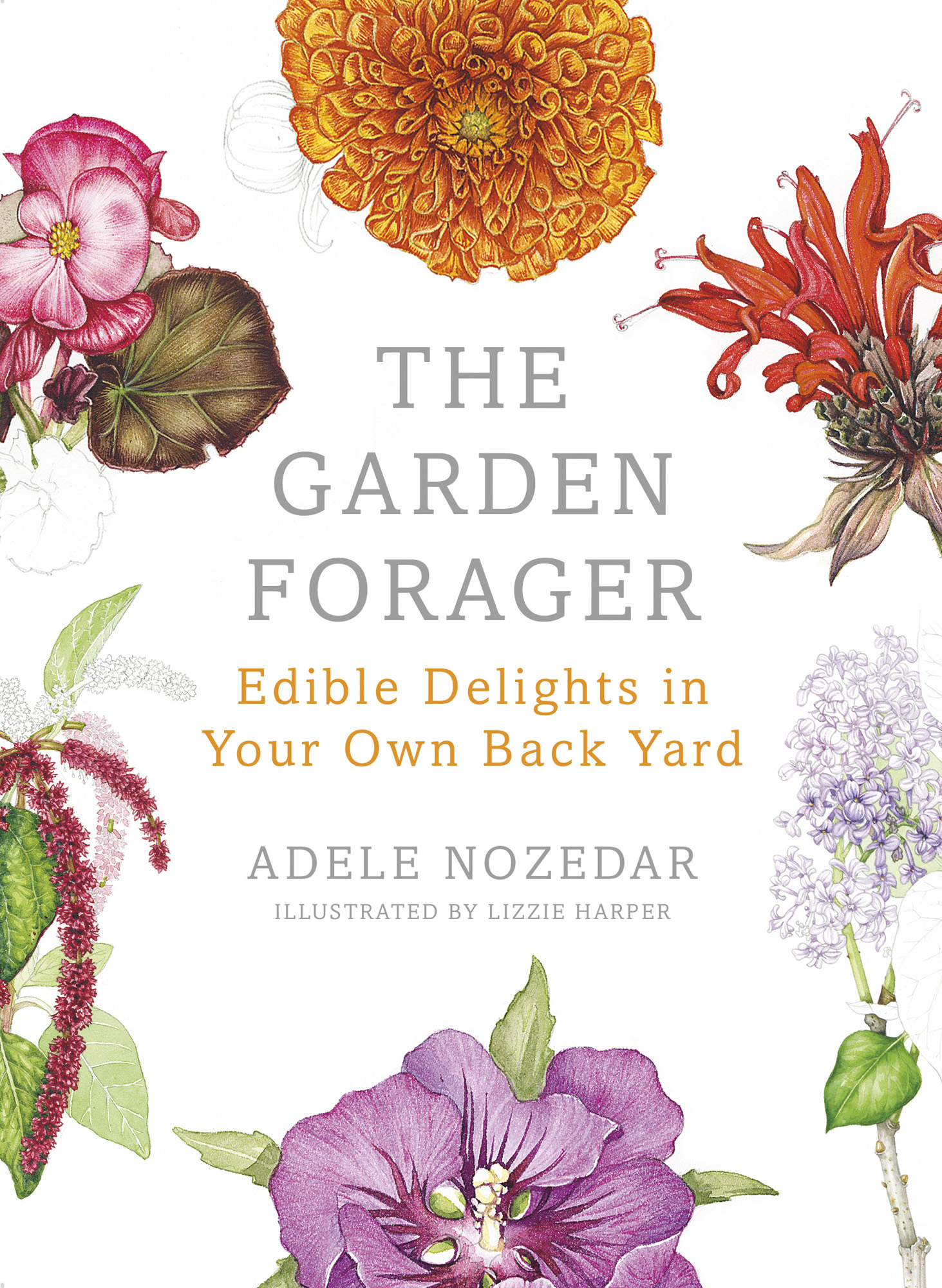

The Garden Forager explores over 40 of the most popular garden plants that have edible, medicinal or even cosmetic potential, accompanied by recipes, remedies, and interesting facts, and illustrated throughout in exquisite watercolours by Lizzie Harper.

This beautifully illustrated book redefines how we look at our gardens and unleashes the unknown potential of everyday plants making it a must-have for anyone interested in gardening, cooking, or foraging.

About the Author

Adele Nozedar is the author of The Hedgerow Handbook. She regularly leads foraging workshops and tours at major festivals across the UK. Previously, she was in a cult indie band, then ran her own indie record label and became A&R Director/General Manager of a major record company. Her wide-ranging passions are reflected in her books, which include The Hedgerow Handbook (2012), The Signs and Symbols Sourcebook (2011), The Secret Language of Birds (2006) and The Element Encyclopedia of Native Americans (2013).

Putting in the Seed

Robert Frost

You come to fetch me from my work to-night

When suppers on the table, and well see

If I can leave off burying the white

Soft petals fallen from the apple tree

(Soft petals, yes, but not so barren quite,

Mingled with these, smooth bean and wrinkled pea;)

And go along with you ere you lose sight

Of what you came for and become like me,

Slave to a springtime passion for the earth.

How Love burns through the Putting in the Seed

On through the watching for that early birth

When, just as the soil tarnishes with weed,

The sturdy seedling with arched body comes

Shouldering its way and shedding the earth crumbs.

No fences in Eden

If you take a short drive out of Abergavenny into the rolling, folded hills of the old industrial part of South Wales around the small town of Blaenavon, youll come to an amazing place, dubbed the Forgotten Landscapes. This is a designated UNESCO World Heritage site and therefore in the same league as more famous landmarks such as the Pyramids or the Great Wall of China. This particular stretch of the landscape is significant because the hidden hollows of these hills are the crucible in which the Industrial Revolution was founded. Around Blaenavon, the old iron works with their blast furnaces stand, still erect but derelict, bleak, disused, a humbling reminder that the works of mankind are barely a speck of dust in the greater picture. And growing out of a fissure in the side of a grim, tumbledown tram bridge is a lush, lavish, lovely but rather exotic (for this neck of the woods) fig tree.

How on earth did it get there? Did some homesick Italian immigrant, come to work in the furnaces over 200 years ago, sit on the bridge one day, legs dangling over the edge, forlornly eating the very last fig that hed brought from Tuscany and thinking of the sunny home hed never return to? Plants tell stories; this particular fig is a mute piece of living archaeology. Well never know how it got there, but its fun to try and guess.

Native to Western Asia and the Middle East, this sprawling fig tree couldnt have chosen many places quite so dissimilar to the arid dryness of its original sunny home. The higher hills of Wales are notorious for their weeks of snow, determined frosts and for the winds that whip the breath from your lungs and polish your nose and cheeks shiny red. Luckily, lots of the plants that have successfully spread themselves around the planet via various means wind, water, the migrations of mammals and birds, even on the soles of our shoes are extremely adaptable to alien habitats; jasmine, for example, which started out in the exotic East, but grows so well in Switzerland that plant collectors at one time thought that it must be indigenous to that country. Ah, plant collectors! Lets not forget the contribution these pioneers made, in helping plants to cross boundaries political, cultural and horticultural.

Many of our common cultivated garden plants shared similarly exotic, exciting and adventurous pasts before they became part of our domestic landscape. Its also a bit of an eye-opener to find that many of the plants that we now cultivate purely because theyre ornamental were once highly regarded not for their looks but for their flavour. Many of our garden favourites, primped and pushed and preened and trained not to slouch at county shows, are equally at home in dishes in other parts of the world. Hosta, for example, is known as urui in Japan and served with sesame sauce; sumac, a lovely ornamental tree seen in many gardens, yields an exotic spice that can be bought in the souks of Istanbul. Pyracantha (fire-thorn), so common that Id happily bet youve got one growing within a few metres of your house, yields berries which were once a popular ingredient in both sweet and savoury dishes in the UK. Much of this, I suspect, is down to fashion; food fads come and go.

Where our indigenous wild plants carry with them charming stories and superstitions, and have old wives tales and folk names attached to them which give a clue as to their uses and form part of our genetic memory, the plants that we think of as cultivated, and which the major part of this book deals with, tend to come from other, foreign places and dont have quite the same threads of nostalgia for us. And yet they too have their stories, though they belong to different times and to different peoples. After all, every plant on this planet started life as a wild thing; its when the plant is unfamiliar that it becomes exotic. Having said that, I have included a small number of plants native to the British Isles that are possibly overlooked or misunderstood, such as the strawberry tree ( Arbutus unedo ).

To garden or to cook?

I hope that this book will be a journey of discovery for people who enjoy their garden and cooking. It may not fundamentally alter the way you work either in your garden or in your kitchen, but I do hope it will make you look at things in a different way, and maybe, in your mind, youll step into the footsteps of different people in different places. And what youll learn about the plants included here should enhance both your cooking and your gardening, as well as contribute to your general health and well-being. Nutritionists tell us that we need to eat 30 different foodstuffs per day, and if a small handful of these can come from your garden or window box, then so much the better.