American Heretics

Catholics, Jews, Muslims, and the History of Religious Intolerance

Peter Gottschalk

Foreword by Martin E. Marty

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

AMERICAN HERETICS

Copyright Peter Gottschalk, 2013

All rights reserved.

For information, address St. Martins Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

First published in 2013 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN in the U.S.a division of St. Martins Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

ISBN: 978-1-137-27829-6

Our eBooks may be purchased in bulk for promotional, educational, or business use. Please contact the Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at 1-800-221-7945, ext. 5442, or by e-mail at .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gottschalk, Peter, 1963

American heretics: Catholics, Jews, Muslims, and the history of religious intolerance / Peter Gottschalk.

pages cm

1. United StatesReligionHistory. 2. Religious discriminationUnited StatesHistory. 3. Religious toleranceUnited StatesHistory. 4. ReligionsRelations. I. Title.

BL2525.G687 2013

305.60973dc23

2013019003

A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library.

Design by Letra Libre

First edition: November 2013

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America.

This book is dedicated to all the generations of my family

especially my parents

Rudolf and Babette Gottschalk

who taught me

to question

and care

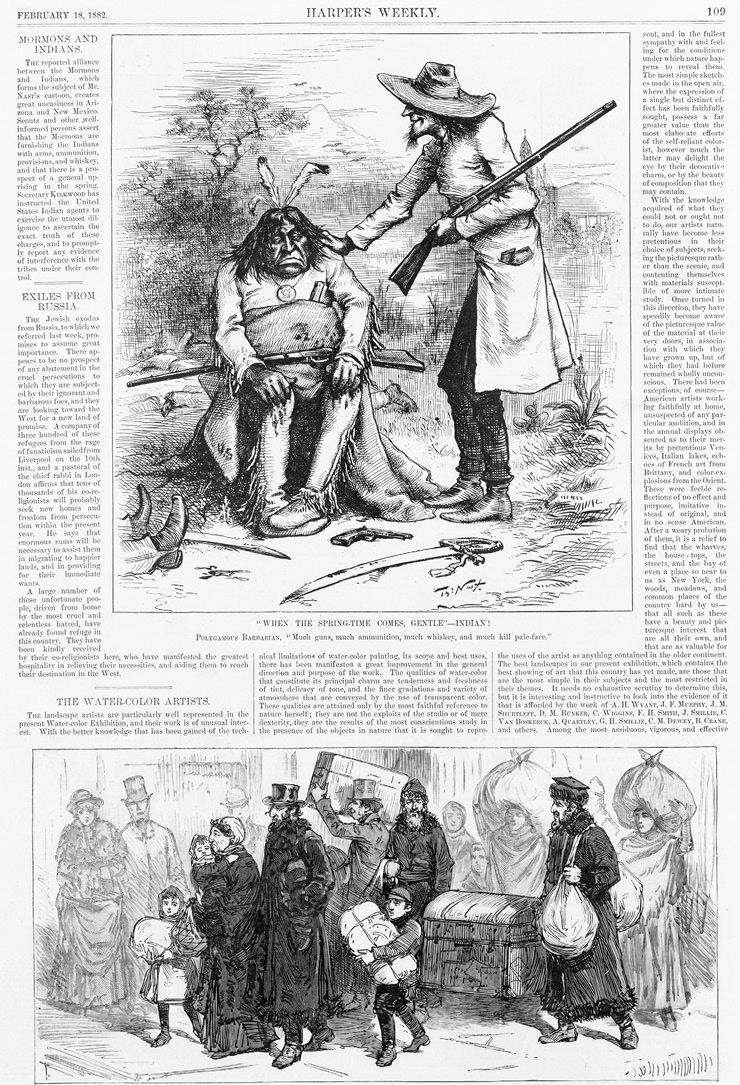

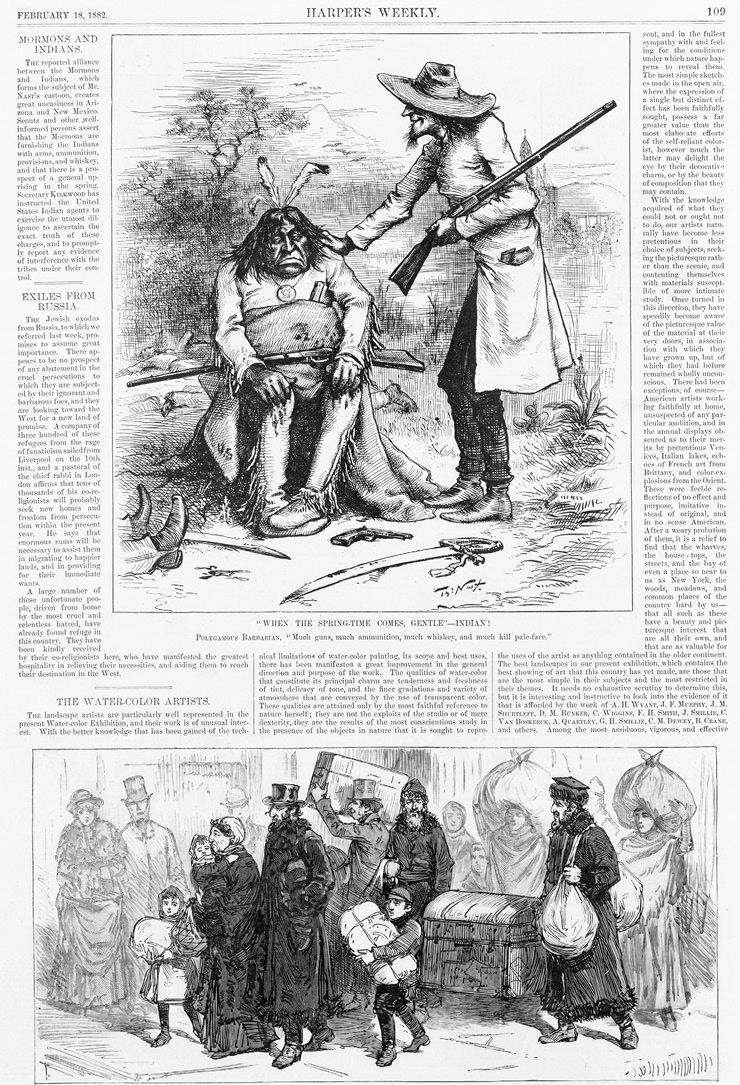

Mormons, Indians, and Jews, as depicted in Harpers Weekly (February 18, 1882). Courtesy of Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-105116.

Contents

List of Illustrations

The wording of an illustration label given in quotes derives from the original artist, photographer, or publisher.

Foreword

Since heresy derives from the Greek word for choosing or choice, we may think of heretics as choosers. Americans in this sense are all choosy, since, however they got to where they are, be it religiously or anti-religiously, they are free to be something else, and millions put that freedom to work. On those terms, every American, even one who chooses to stay put with an inherited, established faith or converts to a new faith community or a non-faith, can be a heretic in the eyes and minds of those who have made other choices.

That word other is what gets us heretics into trouble. In this book that other may be a witch or a Quaker, a Sioux who dances the Ghost Dance or the Irish Catholic, who dances to her own tunes. Jews have been the other to American Christians for more than three centuries, so, in Gottschalks observation and analysis, they were long victims because they had made the wrong choice of parents. To complete his mini-roll-call of choosersthe author chose his examples wellhe focuses on those who really upset neighbors who were settled into what they had considered to be sameness. The upsetters were different, often apart in their sects or cultsnow politically classified as NRMs, members of New Religious Movements.

To majorities who feared them, wished they would go away, or victimized them, it was usually the intensity of the faith of the other that agitated them. So they were labeled fanatics. Peter Finley Dunne, an Irish-American humorist, defined a fanatic is a man that does what he thinks the Lord would do if He knew the facts of the case.those who opposed such fanatics took up the weapons of fanaticism themselves.

With myriad examples for a religion-scholar like Gottschalk to choose from, we who read him will judge the book in part by the choices he made and his explanation of why all this matters. His stories are attractive, but the author has a serious purpose and little time to call readers attention to it. We re-learn that there is trouble whenever we as citizens are prejudiced and intolerant, especially when we put our prejudices to work at the expense of others. Ignorance and hatred of others are dangerous in our crowded, weapon-filled world.

Just when readers are ready to ask how can we do better? Gottschalk accommodates them with a capital-lettered version of that question: How Can We Do Better? It heads the last chapter which the author and many others of us hope can become the impetus to find new ways to move beyond the suspicion and hatred that plague the republic time and again. To reinforce his point, lets try italics: We Can Do Better. And that chapter suggests how.

Martin E. Marty

Fairfax M. Cone Distinguished Professor Emeritus,

The University of Chicago

Acknowledgments

I am first and foremost indebted to Marissa Napolitano and Kayla Reiman, whose persistent and insightful work as research assistants provided many of the materials and insights that inform this book. During my research, the staff of Wesleyan Universitys library system and the Library of Congress proved invaluable, especially Eric Frazier in Rare Books and Jeff Bridgers in Prints and Photographs. I also thank my daughter, Ariadne Skoufos, for her contributions in editing parts of the manuscript.

A number of colleagues offered crucial, critical readings of chapters of this book, including Sumbul Ali-Karamali, J. Spencer Fluhman, Eugene Gallagher, Anne Greene, Bruce Lawrence, Edward T. ODonnell, Annalise Glauz-Todrank, David Walker, andmost especiallyJeremy Zwelling. Others provided feedback on various elements of the argument, including Mathew N. Schmalz, Elizabeth McAlister, John Esposito, Winnifred Fallers Sullivan, and Raymond J. DeMallie. As always, my gratitude also goes to my students, whose comments in our seminars help shape my thinking and introduce new perspectives.

The administration at Wesleyan University have been responsible for the financial and sabbatical assistance that made this volume possible. I especially appreciate the support of Dean Gary Shaw and Provost Rob Rosenthal.

I thank all of the staff at Palgrave Macmillan who helped steer this project from idea to manuscript to book. Special appreciation goes to Laura Lancaster, Katherine Haigler, and Georgia Maas, for their detailed editing and Burke Gerstenschlager for his continued support.

Parts of chapters six and seven appeared in Religion Out of Place: Islam and Cults as Perceived Threats in the United States, published in From Moral Panic to Permanent War: Lessons and Legacies of the War on Terror, edited by Gershon Shafir, Everard Meade, and William Aceves. The material is used with the permission of Routledge Press.

Finally, as ever, I am always in the debt of my family and friends, who saw less of me as I wrote this book yet continued to show unselfish support despite my absence. Beginning with my daughter and radiating outward across the bonds of love, I assure you that your presence, support, and affection run as lifeblood through these words.

Introduction

I was raised an Islamophobe.

I was brought up to be scared of Muslims and of Islam. When I imagined Muslims, I pictured men with beards, wearing flowing white garments, sometimes with guns in their hands.

When I write that I was raised this way, I dont mean that my parents instilled these lessons in my head (in fact, they would be responsible for important experiences that undermined my stereotypes). Children are not only brought up by their parents and immediate family, but by larger society as well. The society in which I was raised in the 1960s and 70s saw Muslims through the lens of a series of conflicts: the 1973 oil embargo by OPEC, the 1979 Iranian hostage crisis, and the various Arab-Israeli conflicts. It communicated these negative stereotypes about Arabs and Muslims (usually and incorrectly depicting one as necessarily the other) through entertainment and news media: scimitar-wielding oil ministers in political cartoons, ill-shaven terrorists in television dramas, leering men lusting to add women to their harems in Hollywood films, and perennially violent Muslim-majority countries in newspaper and news reports.

Next page