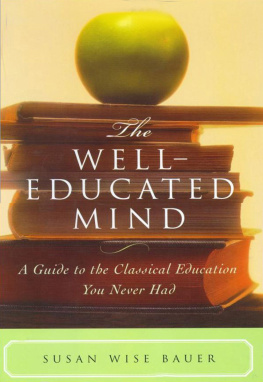

ALSO BY SUSAN WISE BAUER

The Story of Western Science: From the Writings of

Aristotle to the Big Bang Theory

(W. W. NORTON, 2015)

The History of the World Series

(W. W. NORTON)

The History of the Ancient World (2007)

The History of the Medieval World (2010)

The History of the Renaissance World (2013)

The Art of the Public Grovel

(PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2008)

The Story of the World: History for the Classical Child

(PEACE HILL PRESS)

Volume I: Ancient Times (2002)

Volume II: The Middle Ages (2003)

Volume III: Early Modern Times (2003)

Volume IV: The Modern World (2004)

The Writing With Ease Series

(PEACE HILL PRESS, 2008-2010)

The Writing With Skill Series

(PEACE HILL PRESS, 2012-2013)

WITH JESSIE WISE

The Well-Trained Mind:

A Guide to Classical Education at Home

(W. W. NORTON, 2009)

THE ORIGINAL EDITION of this book would never have been completed without the help of Sara Buffington, who worked on the thankless task of clearing permissions and kept Peace Hills own publishing efforts running seamlessly along; Justin Moore, who made endless library trips for me (including the ones in which he returned overdue books I was too embarrassed to show up with), checked facts, entered soul-destroying columns of ISBN numbers, introduced me to the music of The Proclaimers, compounded all this with intelligent readings (of the history chapter in particular), and helped me keep my in-box clear; Lauren Winner, scholar and writer, who read the history chapter and offered invaluable help; John Wilson, editor of Books & Culture; Maureen Fitzgerald of the College of William and Mary; and my parents, Jay and Jessie Wise, who gave me every moral and practical support imaginable.

For this revision, Im grateful as always to my editor at W. W. Norton, Starling Lawrence, who keeps reading what I write, and always knows of a better restaurant than the one Id planned on. Thanks also to Nortons Ryan Harrington, who answers his email promptly, always finds the answers, and does what he says hell do.

I am deeply indebted to Patricia Worth, executive assistant extraordinaire; Justin Moore (again); Richie Gunn, for the illustrations; the able and charming Michael Carlisle at Inkwell Management; the amazing Julia Kaziewicz, for help with permissions as well as expert advice on many subjects academic; Greg Smith, for his insights on the great texts of science (I didnt take all of his advice, so he gets credit but no blame for ); and, as always, my husband Peter.

For my mother

who taught me to read,

and my father

who gave me all of his favorite books

All civilization comes through literature now, especially in our country. A Greek got his civilization by talking and looking, and in some measure a Parisian may still do it. But we, who live remote from history and monuments, we must read or we must barbarise.

WILLIAM DEAN HOWELLS,

The Rise of Silas Lapham

T HE YEAR I turned thirty, I decided to go back to graduate school. Id taken years off from school to write, teach literature as an adjunct lecturer, have four children. Now I was back in the classroom, on the wrong side of the teachers desk. All the graduate students looked like teenagers. And graduate programs arent designed for grownups; I was expected to stuff my family into the schedule designed for me by American Studies, live off a stipend of six thousand dollars per year while forgoing all other gainful employment, and content myself with university-sponsored health insurance, which supplied bare-bones coverage and classified anesthesia during childbirth as a frill. And I found myself dreading the coming year of classes. Id been teaching and directing discussions for five years. I didnt think I could bear to be transformed back into a passive student, sitting and taking notes while a professor told me what I ought to know.

But to my relief, graduate seminars werent lectures during which I meekly received someone elses wisdom. Instead, the three-hour weekly sessions turned out to be the springboard of a self-education process. Over the next year and a half, I was directed toward lists of books and given advice about how to read them. But I was expected to teach myself. I read book after book, summarized the content of each, and tried to see whether the arguments were flawed. Were the conclusions overstated? Drawn from skimpy evidence? Did the writers ignore facts, or distort them to support a point? Where did their theories break down? It was great fun; trashing the arguments of senior scholars who are making eighty times your annual stipend is one of the few compensations of grad-student serfdom.

All of this reading was preparation for my seminars, in which graduate students sat around long tables and argued loudly about the book of the week. The professor in charge pointed out our sloppy reasoning, corrected our misuses of language, and threw water on the occasional flames. These (more or less) Socratic dialogues built on the foundation of the reading I was doing at home. On evenings when I would normally have been watching The X-Files or scrubbing the toilet, I read my way through lists of required books with concentrated attention. The housework suffered and I missed Mulders departure from spook hunting; but I found myself creating whole new structures of meaning in my mind, making connections between theories and building new theories of my own on top of the links. I wrote better, thought more clearly, read more.

I also drove myself into work-induced psychosis. I stayed up late at night to finish my papers and got up early with the baby; I wrote my dissertation proposal on the living room floor, with a Thomas the Tank Engine track in construction all around me; I spent the night before my required French exam washing my four-year-olds sheets and pillows after he caught the stomach flu; I sat through numerous required workshops in which nothing of value was said.

Here is the good news: You dont have to suffer through the graduate school wringer in order to train your mindunless you plan to get a job in university teaching (not a particularly strong employment prospect anyway). For centuries, women and men undertook this sort of learningreading, taking notes, discussing books and ideas with friendswithout subjecting themselves to graduate-school stipends and university health-insurance policies.

Indeed, university lectures were seen by Thomas Jefferson as unnecessary for the serious pursuit of historical reading. In 1786, Jefferson wrote to his college-age nephew Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr., advising him to pursue the larger part of his education independently. Go ahead and attend a course of lectures in science, Jefferson recommended. But he then added, While you are attending these courses, you can proceed by yourself in a regular series of historical reading. It would be a waste of time to attend a professor of this. It is to be acquired from books, and if you pursue it by yourself, you can accommodate it to your other reading so as to fill up those chasms of time not otherwise appropriated.

Next page