THE INFIDEL AND THE PROFESSOR

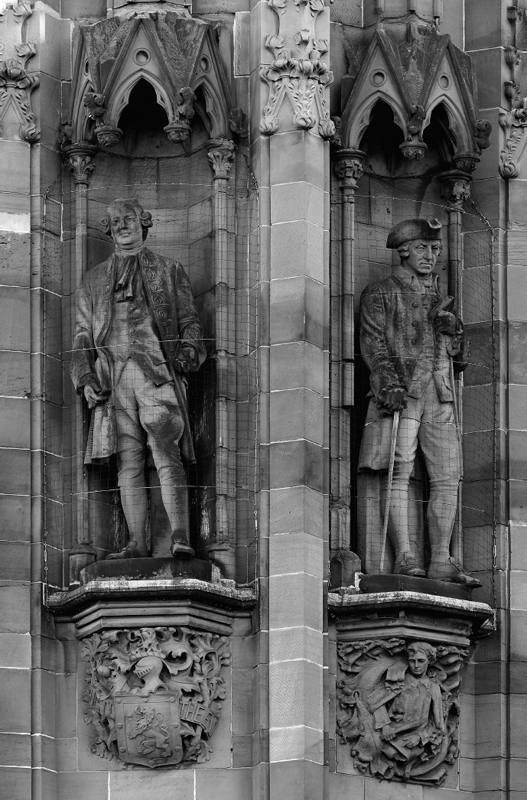

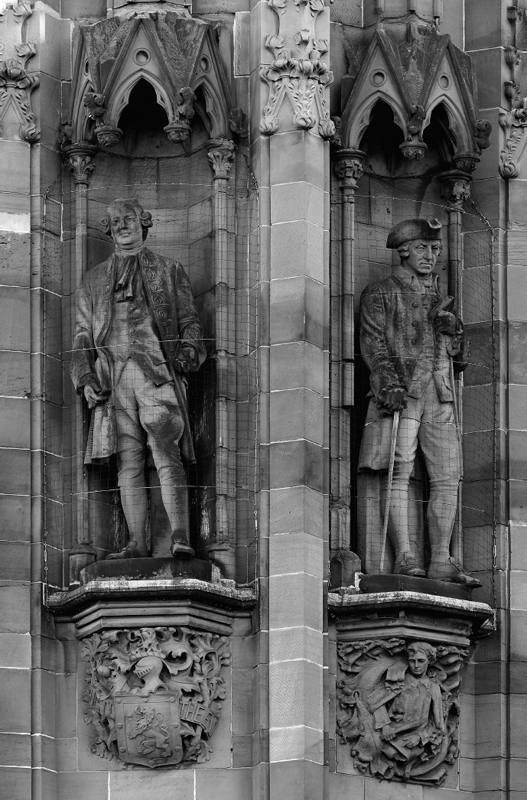

statues of Hume and Smith. Original photo taken by staff. Scottish National Portrait Gallery

THE

INFIDEL

AND THE

PROFESSOR

DAVID HUME,

ADAM SMITH,

AND THE

FRIENDSHIP

THAT

SHAPED

MODERN

THOUGHT

DENNIS C. RASMUSSEN

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

COPYRIGHT 2017 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

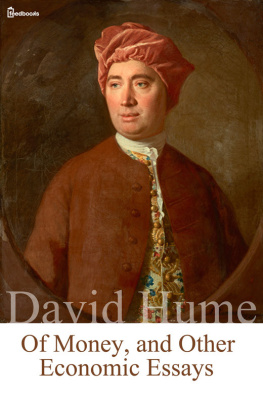

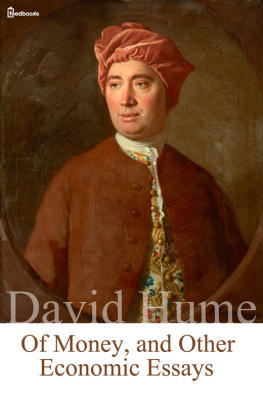

Jacket art: (Left) David Hume, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, (right) Adam Smith, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection; The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ISBN 978-0-691-17701-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017936619

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon and The Fell Types The Fell Types are digitally reproduced by Igino Marini.

www.iginomarini.com

Printed on acid-free paper.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Upon the whole, I have always considered him, both in his lifetime and since his death, as approaching as nearly to the idea of a perfectly wise and virtuous man, as perhaps the nature of human frailty will permit.

ADAM SMITH ON DAVID HUME

Without doubt you have read what is called the Life of David Hume, written by himself, with the letter from Dr. Adam Smith subjoined to it. Is not this an age of daring effrontery? My friend Mr. [John] Anderson paid me a visit lately; and after we had talked with indignation and contempt of the poisonous productions with which this age is infested, he said there was now an excellent opportunity for Dr. Johnson to step forth. I agreed with him that you might knock Humes and Smiths heads together, and make vain and ostentatious infidelity exceedingly ridiculous. Would it not be worth your while to crush such noxious weeds in the moral garden?

JAMES BOSWELL TO SAMUEL JOHNSON

Adam Smith, Letter from Adam Smith, LL.D. to William Strahan, Esq., in David Hume, Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary, ed. Eugene F. Miller (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, [1777] 1987), xlix.

James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (London: William Pickering, [1791] 1826), 1045.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

D AVID HUME IS widely regarded as the greatest philosopher ever to write in the English language, and Adam Smith is almost certainly historys most famous theorist of commercial society. Remarkably, the two were best friends for most of their adult lives. This book follows the course of their friendship from their first meeting in 1749 until Humes death more than a quarter of a century later, examining both their personal interactions and the impact that each had on the others outlook. We will see them comment on one anothers works, support one anothers careers and literary ambitions, and counsel one another when needed, such as in the aftermath of Humes dramatic quarrel with Jean-Jacques Rousseau. We will see them make many of the same friends (and enemies), join the same clubs, and strive constantlythough with less success than they always hopedto spend more time together. We will also see them adopt broadly similar views, but very different public postures, with respect to religion and the religious; indeed, this will be a running theme throughout the book.

Although I am a professor and hope that this book will contribute to the scholarly study of Hume and Smith, it was written not just for academics but for anyone interested in learning more about the lives and ideas of these two giants of the Enlightenment, and about what is arguably the greatest of all philosophical friendships.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T HIS BOOK WAS an absolute joy to write, and I am glad to have an opportunity to express my appreciation to some of those who helped to make it so. I must begin with a general word of thanks to Tufts University, particularly to the Department of Political Science for providing a congenial academic home and to the Faculty Research Awards Committee for generous funding. I am grateful to Bill Curtis, Emily Nacol, Rich Rasmussen, Michelle Schwarze, and two anonymous reviewers for reading a draft of the book and providing helpful comments, and to Felix Waldmann for pointing me toward useful resources. I have benefited enormously from the conversation, encouragement, and insight of many other scholars of Hume, Smith, and the Enlightenment more broadly. It would be impossible to name all of these individuals here, but I must single out Sam Fleischacker, Michael Frazer, Michael Gillespie, Ruth Grant, Charles Griswold, and Ryan Hanley. I am grateful for the assistance provided by the staffs of the Tisch Library at Tufts University, the Widener and Lamont Libraries at Harvard University, the Beinecke Library at Yale University, the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, the British Library and Dr. Williamss Library in London, the Edinburgh University Library and the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh, the University of Glasgow Library, and the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland in Belfast. I would also like to thank my editor, Rob Tempio, and the whole team at Princeton University Press for all of the effort and care that went into making the book as good as it could be.

As always, my deepest thanks go to my wife, Emily, and now also our son, Sam. Given that this book focuses on a friendship, however, this one is dedicated to my friends. I can think of few better wishes for Sam than that he be as fortunate in his friends as I have been.

THE INFIDEL AND THE PROFESSOR

INTRODUCTION

DEAREST FRIENDS

A S DAVID HUME lay on his deathbed in the summer of 1776, much of the British public, both north and south of the Tweed, waited expectantly for news of his passing. His writings had challenged their viewsphilosophical, political, and especially religiousfor the better part of four decades. He had experienced a lifetime of abuse and reproach from the pious, including a concerted effort to excommunicate him from the Church of Scotland, but he was now beyond their reach. Everyone wanted to know how the notorious infidel would face his end. Would he show remorse or perhaps even recant his skepticism? Would he die in a state of distress, having none of the usual consolations afforded by belief in an afterlife? In the event Hume died as he had lived, with remarkable good humor and without religion. The most prominent account of his calm and courageous end was penned by his best friend, a renowned philosopher in his own right who had just published a book that would soon change the world. While

Next page