Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

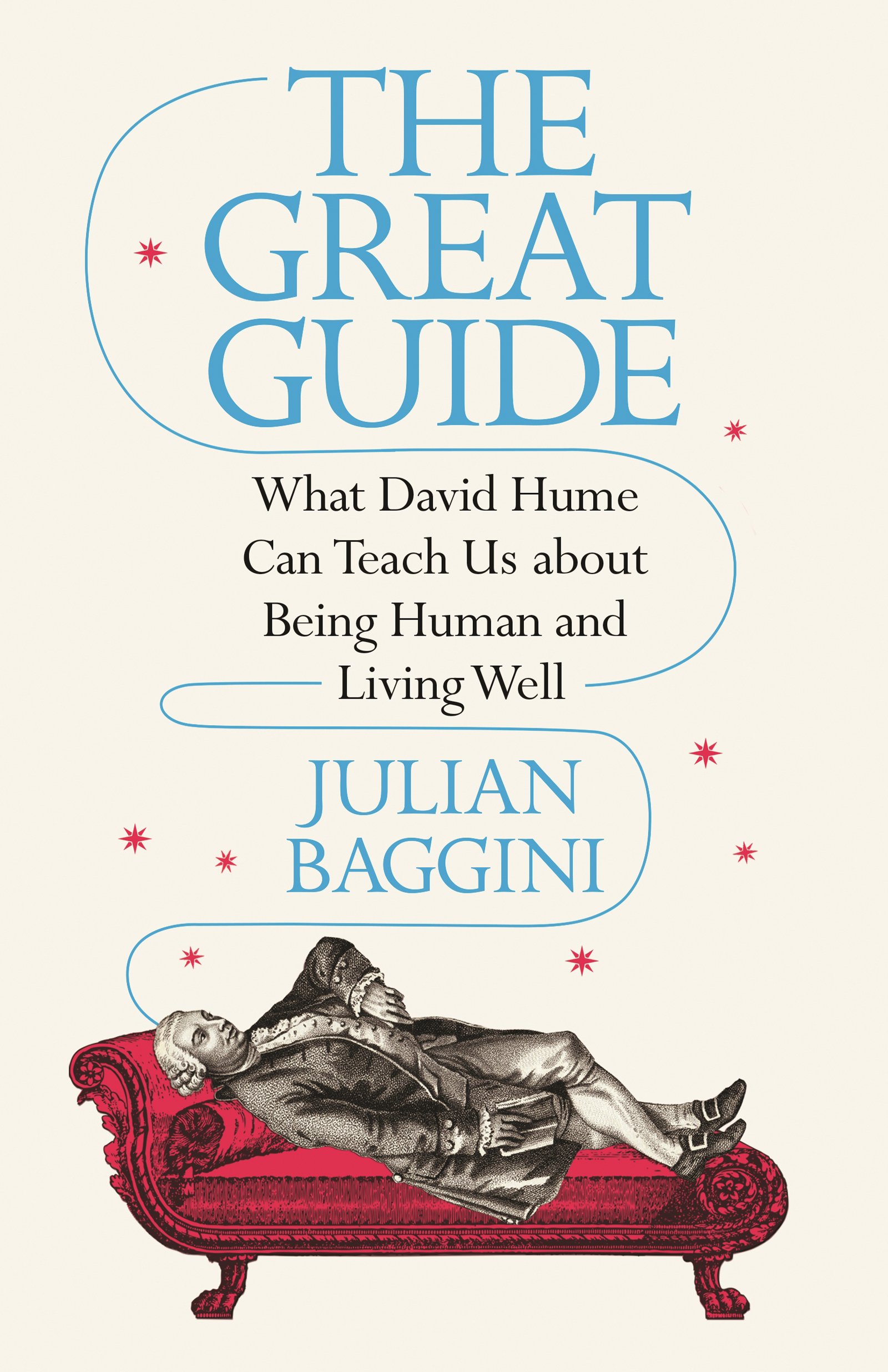

INTRODUCTION

Scotlands Hidden Gem

Standing at the top of Calton Hill, close to the center of Edinburgh, is Scotlands National Monument, built to commemorate the Scottish soldiers and sailors who died in the Napoleonic Wars. Modeled on the Parthenon in Athens, it ended up resembling its inspiration more than its designers intended. While the Parthenon is half destroyed, the National Monument is only half constructed, after work was abandoned in 1829 due to lack of funds.

The monuments evocation of classical Greece in modern Scotland might at first seem incongruous. When Plato and Aristotle were laying down the foundations of Western philosophy, Scotland, like the rest of Britain, was still a preliterate society. However, by the early eighteenth century, it could proudly claim to be the successor of Athens as the philosophical capital of the world. Edinburgh was leading the European Enlightenment, rivaled only by Paris as an intellectual center. In 1757, David Hume, the greatest philosopher the city, Britain, and arguably even the world had ever known, said with some justification that the Scottish shoud really be the People most distinguishd for literature in Europe.

FIGURE 1. Scotlands National Monument on Calton Hill, Edinburgh.

The city produced two of the greatest thinkers of the modern era. One, the economist Adam Smith, is widely known and esteemed. The other, Hume, remains relatively obscure outside academia. Among philosophers, however, he is often celebrated as the greatest among their ranks of all-time. When thousands of academic philosophers were recently asked which non-living predecessor they most identified with, Hume came a clear first, ahead of Aristotle, Kant, and Wittgenstein. Hume is as adored in academe as he is unknown in the wider world.

Many scientistsnot usually great fans of philosophyalso cite Hume as an influence. In a letter to Moritz Schlick, Einstein reports that he read Humes Treatise with eagerness and admiration shortly before finding relativity theory. He goes so far as to say that it is very well possible that without these philosophical studies I would not have arrived at the solution.

Not even his academic fans, however, sufficiently appreciate Hume as a practical philosopher. He is most known for his ideas about cause and effect, perception, and his criticisms of religion. People dont tend to pick up Hume because they want to know how to live. This is a great loss. Hume did spend a lot of time writing and thinking about often arcane metaphysical questions, but only because they were important for understanding human nature and our place in the world. The most abstract speculations concerning human nature, however cold and unentertaining, become subservient to practical morality; and may render this latter science more correct in its precepts, and more persuasive in its exhortations. For instance, cause and effect was not an abstract metaphysical issue for him but something that touched every moment of our daily experience. He never allowed himself to take intellectual flights of fancy, always grounding his ideas in experience, which he called the great guide of human life. Hume thus thought about everyday issues in the same way as he did about ultimate ones.

To see how Hume offers us a model of how to live, we need to look not only at his work but at his life. Everyone who knew Hume, with the exception of the paranoid and narcissistic Jean-Jacques Rousseau, spoke highly of him. When he spent three years in Paris in later life he was known as le bon David, his company sought out by all the salonistes. Baron dHolbach described him as a great man, whose friendship, at least, I know to value as it deserves.

Hume didnt just write about how to livehe modeled the good life. He was modest in his philosophical pretensions, advocating human sympathy as much as, if not more than, human rationality. He avoided hysterical condemnations of religion and superstition as well as overly optimistic praise for the power of science and rationality. Most of all, he never allowed his pursuit of learning and knowledge to get in the way of the softening pleasures of food, drink, company, and play. Hume exemplified a way of life that is gentle, reasonable, amiable: all the things public life now so rarely is.

What Hume said and did form equal parts of a harmonious whole, a life of the mind and body that stands as an inspiration to us all. I want to approach David Hume as a synoptic whole, a person whose philosophy touches every aspect of how he lived and who he was. To do that, I need to approach his life and work together. I have followed in Humes biographical and sometimes geographical footsteps to show why we would be wise to follow in his philosophical ones too.

When we look at his life and person, we also understand better why Hume has not crossed over from academic preeminence to public acclaim. In short, he lacks the usual characteristics that give an intellectual mystique and appeal. He is not a tragic, romantic figure who died young, misunderstood, and unknown or unpopular. He was a genial, cheerful man who died loved and renowned. His ideas are far too sensible to shock or not obviously radical enough to capture our attention. His distaste for enthusiastsby which he meant fanatics of any kindmade him too moderate to inspire zealotry in his admirers. These same qualities that made him a rounded, wise figure prevented him from becoming a cult one.

If ever there were a time in recent history to turn to Hume, now is surely it. The enthusiasts are on the rise, in the form of strongman political populists who assert the will of the people as though it were absolute and absolutely infallible. In more settled times, we could perhaps use a Nietzsche to shake us out of our bourgeois complacency, or entertain Platonic dreams of perfect, immortal forms. Now such philosophical excesses are harmful indulgences. Good, uncommon sense is needed more than ever.