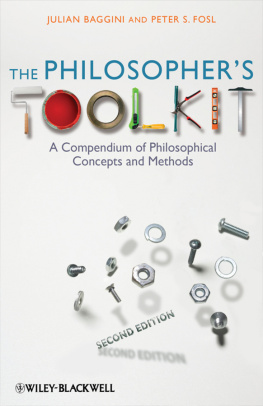

Julian Baggini and Peter S. Fosl

To Joseph P. Fell and Lucy O'Brien

Contents

xiii

xv

Alphabetical List of Entries

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Peter's spouse, Catherine Fosl, and his children, Elijah Fosl and Isaac Fosl van-Wyke, for their patience and support; Avery Kolers for advice on the contents; Jack Furlong and Ellen Cox for their insight; Maggie Barr for proofreading the text; and Transylvania University's Jones Grant program for underwriting Peter's intercontinental travel.

We would also like to thank Jeff Dean and Danielle Descoteaux at Blackwell for their support and patience, as well as the anonymous referees for their thoughtful, thorough, helpful comments, and for their encourage- ment.Thanks also to Charlotte Davies, Annie Jackson, and David Williams at The Running Head for their remarkably thorough tidying up of the manuscript. We are also deeply grateful to all those who have built and who maintain the Internet. Without it, our work together and our friendship would have never come to exist.

Julian Baggini

Peter S. Fosi

Introduction

How should you think about ethics? It's a deceptively simple question. Certainly, you should think well, think clearly, think accurately, and - if it's possible in ethics - think rightly. But how exactly can you set about doing all this?

One way to approach the topic is to try to establish a general theory that attempts to do things like determine the true nature of ethics, define the meaning of ethical terms, formulate fundamental moral principles, and place those principles in a hierarchy. This way of thinking about ethics, in short, tries to produce a theory that pretty much answers all the theoretical questions anyone might ask.

Having accomplished this, of course, you also have to explain why your general theory is better than all the rest, and you have to repel the various challenges that critics are certain to advance. After producing such a theory and defending it, you next set about applying your theory to real-life moral problems, demonstrating how it resolves disputes and answers questions about what to do in various actual circumstances.

One problem with this kind of approach, however, is that more than two millennia of moral philosophy have led to little consensus about the fundamental nature of ethics, the hierarchy of moral principles, or the way to apply them in the real world.Worse, some respectable thinkers have rejected the idea that reaching consensus about such things is even possible.

Meanwhile, of course, the world goes on, tangled in the most profound sorts of moral struggle. If anything, the demand for meaningful and effective moral thinking has become greater than ever. Moral thinking and reasoning, then, despite the limitations of moral philosophy, can neither be put on hold until agreement is reached nor abandoned altogether. Even amoralists need to get clear on what they're rejecting.

The fact that theoretical consensus about moral issues hasn't been reached doesn't mean it can't be reached. But perhaps there's another method, another way to think about ethical matters, a way that can bring real intellectual force to bear upon the moral controversies that populate the world but doesn't require a univocal, general moral theory.

Rather than trying to determine a single, complete ethical theory that answers all the relevant moral questions that may arise, and defeats all its competitors, perhaps one might instead (or also) try to gain a kind of mastery or at least facility with some of the many different theories, concepts, principles, and critiques concerned with ethics that moral philosophers have produced over the ages. The Ethics Toolkit aspires to help those engaged in moral inquiry and reflection to do just that. By placing a selection of insights from different moral theorists and theories side by side, we hope to show readers something about ethics that may go missing in the contests among ethical theories.

We hope to show how many of the concepts and ideas collected under the umbrella of ethical theory have a wider and more complex range of application than can sometimes appear. There are many voices composing the moral discourses of our age, and these different voices address many different problems in different ways. Many tools are necessary to hear them and to respond properly to them, not a single voice or a single tool.

Indeed, anyone who wants to deliberate and converse with others about the major moral concerns that occupy people today must be able to draw upon not just a single well-crafted theory but more broadly upon the rich and diverse work of the past 2,500 years of moral philosophy. Competent thinkers simply must have in their possession a well-stocked "toolkit" containing a host of intellectual instruments for careful, precise, and sophisticated moral thinking.

By producing a compendium like this we also hope to provide readers with a deeper and subtler sense of how different ideas and methods may be enlisted so that people might not only think but also act with regard to moral matters in more effective and satisfying ways. Many of the problems that human beings have to deal with are in part conceptual and philosophical. Coming to terms with these problems will require better thinking. Medicines and machines will be needed to help make the world a better place. But, contrary to the charges that are often brought against philosophy, so will the capacity for clear thinking and sound moral deliberation. In this way, we believe that there is a connection between what the ancient Greeks called "knowing that" (theoretical knowledge) and "knowing how" (practical knowledge).

The vision of ethics underwriting The Ethics Toolkit is pluralistic, and unabashedly so, in the sense that it holds that the insights of, say, utilitarianism are of interest and value not only to utilitarians but also to anyone who wishes to engage in moral reflection. This vision of ethics does not, however, imply that the tools described here can simply be picked up and applied blindly to suit whatever need arises. Various tools are more appropriate to certain needs than others. That is not to say that the tools we collect here can or should only be used in a single way. Some may effectively use a screwdriver to take on the same job others would tackle with a hammer. More advanced thinkers may be able to use some of the tools in ways that beginners cannot. Moral thinkers of all abilities will use some tools more than others, using some only rarely.

There are, similarly, different ways to use this text. The Ethics Toolkit can be read cover-to-cover as a course in ethical reasoning. We begin in fart I with the question of the grounds on which ethics stands. We then consider in Part II the most important frameworks that have been constructed to enable us to reason about ethics. Part III describes a number of central concepts in ethical discourse. In Part IV, we look at the ways in which ethical theories and judgments may be critiqued. Finally, we look at the limits of moral reasoning in Part V.